![]()

Estrada or Navarro?

The José Juan Sánchez Vista and Plano of the Alamo

![]()

![]()

Estrada or Navarro?

The José Juan Sánchez Vista and Plano of the Alamo

![]()

by James E. Ivey

Sánchez Navarro's drawings have been evaluated in some detail as critical representations of the Alamo structures by art historian Susan Prendergast Schoelwer, and declared a forgery by Alamo historian Bill Groneman, the ruling skeptic of Alamo studies. This paper will reexamine the Sánchez Navarro drawings and their provenance, in order to clear up some of the confusion about these important documents so that a more balanced evaluation of them can be made.

In 1938, Carlos Sánchez Navarro y Peón, an amateur historian and a member of the prominent Sánchez Navarro ranching family that at one time owned virtually all of Coahuila, published La Guerra de Tejas - Memorias de un Soldado. 2 This little booklet, only 151 pages long, with half that length taken up by an extended historical introduction, appendices, bibliography, and index, transcribed part of the journal of José Juan Sánchez Navarro.3 Entries in the journal, scattered among official indexes and lists in two bound ledger volumes, continued through Sánchez Navarro's career into 1847.4 The journal had apparently been recognized in the ledgers two years earlier, in 1936, and brought to Carlos's attention.5

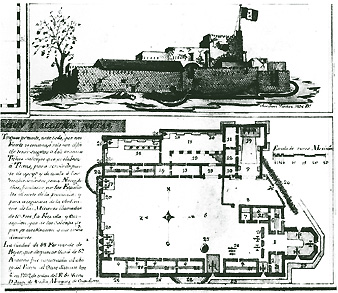

In addition to the journal, the second volume of the ledger contained, on the inside of the front cover, a plan of the battle of the Alamo, showing the fortress itself, cannon batteries of both the Texan defenders and the Mexican army, and troop movements, with an index of features written in as part of the plan.6 The construction lines for a plan of another fort, apparently the old Presidio La Bahía at Goliad, is on the inside of the back cover of the same volume7 - this plan was given up before any more than the San Antonio River was inked. Sánchez Navarro y Peón included a photograph of this plan and its index in La Guerra. We will call this version the "Fuerte" plan, after its title, "Fuerte de San Antonio de Valero." Earlier in the booklet, Carlos included another photograph, this one of a plan and elevation view of the Alamo that were not in the Sánchez Navarro ledgers. We will call these the "Plano," after its title, "Plano Del Fuerte, Su Esplicacion I Algunas Notas," and the "Vista," after its title, "Vista del fuerte de San Antonio de Valero...." The plan and its index were very similar to, but not the same as the Fuerte plan in Sánchez Navarro's ledger.8

In her discussion of the important plans and drawings of the Alamo made before 1850, Susan Schoelwer described the known history of these two drawings, the Vista and Plano, before their publication by Sánchez Navarro y Peón in 1938.9 The Plano's earliest appearance was in one of the sketch-books of Jean Louis Berlandier. Berlandier had been a member of the boundary expedition of General José Manuel de Mier y Terán in 1828-1829, and afterwards lived in Matamoros, on the south side of the Rio Grande where it flowed into the Gulf of Mexico.10 At the time of his death in 1851, he had a large collection of documents and drawings. "In order to preserve visual materials from various sources," said Schoelwer, "Berlandier evidently 'borrowed' original field sketches produced by other artists, then copied them (or had them copied by an assistant) into his notebooks." This collection was broken up after his death and sold to other collectors. One such connoisseur was Henry Raup Wagner, who in 1910 purchased several of the Berlandier drawings and sketch-books from the English collector, Sir Thomas Phillips. Today a large number of the drawings, including many from Henry Wagner, may be found in the Western Americana Collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. The collection includes an undated fair copy of the Plano.11

|

Figure 1. Berlandier copy of the Estrada Vista. Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

|

Berlandier also copied the Vista, and the copy was purchased by Wagner in 1910 (see Figure 1). In 1913 San Antonio became involved in a major controversy between two factions of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (caretakers of the Alamo) and the Governor of Texas, over its proposed reconstruction; the three sides disagreed on the original appearance of the Alamo buildings.12 Wagner, aware of this controversy, in 1913 loaned the Berlandier copy of the Vista to the San Antonio Express, which published it in September, 1913, as evidence of the appearance of the buildings.13 According to the newpaper, "the drawing of the Alamo was done in 1829 by Jose Juan Sánchez Estrada, who was a leading citizen of Mexico many years and who was a member of the International Boundary Commission named by the two Republics." This attribution was based on the information written on the fair copy from the Berlandier collection: "Vista del fuerte de San Antonio de Valero communemente sic llamado del Alamo tomado desde la asotea de la casa de Beramendi en la ciudad de Bexar por Jose Juan Sánchez Estrada View of the fort of San Antonio de Valero, commonly called the Alamo, made from the roof of the Veramendi house in the city of Bexar by José Juan Sánchez Estrada." As Schoelwer describes it, "the association of the drawing with Berlandier ... has caused Sánchez Navarro's Alamo view to be persistently misattributed to one of Berlandier's colleagues on the Mier y Ter.n expedition of 1829.... the copyist deleted the original artist's signature, shortened the caption, and then added to the latter a new line: `por José Juan Sánchez Estrada.' This line, which may well have been simply a case of mistaken identity, remains a puzzle." This attribution was repeated in U.S. publications through at least 1969, although Schoelwer and others have concluded that this was a mistake - "despite the subsequent appearance in Mexico of La Guerra published by Sánchez Navarro y Peón in 1938, with a photograph of the original Vista included and attributed to José Juan Sánchez Navarro, misattribution of this view to Sánchez Estrada persisted ..."14

This confusing sequence of appearances of the Sánchez Navarro drawings in various guises and under various names contributed to the conviction of Alamo historian Bill Groneman that they, and the associated journal, were all forgeries. In 1991 he published Defense of a Legend: Crockett and the de la Peña Diary, a book that argued that the diary of José Enrique de la Peña was a forgery carried out in the early part of the twentieth century.15 For reasons Groneman did not make clear, he also branded the Sánchez Navarro journal and drawings as fakes, and even suggested that they were from the same hand that produced the Peña documents. Two of the circumstances that aroused Groneman's suspicions about the journal and drawings were 1) the arbitrary change in the attribution of the artist from Sánchez Estrada to Sánchez Navarro, and 2) the lack of any original document for some of them.16 Schoelwer, too, states that "the original elevation published in 1938 the Vista cannot presently be located and is not known to have appeared in any other publications," and the same thing can be said of its accompanying plan, the Plano.17 However, this puzzle is not exactly what it seemed to Schoelwer and Groneman, and it now appears that the Berlandier attribution of the Vista drawing to Sánchez Estrada was not a mistake.

|

| figure 2. 1836 map and view of the Alamo by José

Sanchez-Navarro. Benson Latin American Library, UT Austin. |

|

|

It was clear that there had been an original Vista and Plano, and that it had been copied by Berlandier in the 1830s or 1840s, and by Sánchez Navarro y Peón in 1938 - but where was it now and what did it look like? The beginning of the end for the mystery of the missing Vista and Plano began in 1998, when the historian George Nelson published a new version of the Vista and Plano in his book The Alamo: An Illustrated History. 18 Nelson's reproduction was much better than the first photograph published by Sánchez Navarro y Peón, and showed details not included in the earlier publication. The credit line with the photographic reproduction said the original was in the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, and attributed the Vista and Plano to José Juan Sánchez Navarro.

The staff of the BLAC suggested that Nelson's photographs came from a photostat in the collection, the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras." Comparison of this plan with a xerox made available to me by Nelson confirmed that, indeed, Nelson's copy of the View and Plano are enlargements of a small portion of the photostat (see Figure 2).19

The photostat is of a large, complex map, incorporating a number of sections (see Figure 3 to be published).20 The largest of these was the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras Reducido del Original de S. M. L. Staples Por P. Miguel Alvarez, 1828 Map of the Estates of Parras, Reduced from the Original from S. M. L. Staples by P. Miguel Alvarez, 1828," a topographic drawing of part of southern Coahuila filling most of the left half of the map. The principal title, however, was "Copia del Mapa de las fincas y terrenos pertenecientes al ex Marquesado de San Miguel de Aguayo, Sacada del original por José Juan Sánchez Estrada, Coronel de Ejercito Adentro? 1840 Copy of a Map of the property and lands pertaining to the ex-Marquisate of San Miguel de Aguayo, taken from the original by José Juan Sánchez Estrada, Colonel of the Army of the Interior?, 1840," in the lower left-hand corner.

The "Copia del Mapa" was itself copied by Vito Alessio Robles sometime before 1935, probably as part of the research for a series of books he was writing on the history of Coahuila and Texas. On the back of the photostatic copy he donated to the University of Texas in 1935, Alessio Robles wrote:

"El original se encuentra en poder del Señor Francisco Cardenas, Saltillo, Coahuila, esquina de las calles Allende Sur y Lerdo de Tejada Oriente. El plano original esta dibujado a colores y tiene 77 Omega x 71 Omega centimetros. Para la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Texas. Muy atentamente, Vito Alessio Robles, México, D.F., Agosto 22 de 1935 The original is found in the possession of Señor Francisco Cardenas, Saltillo, Coahuila, on the corner of the streets Allende Sur and Lerdo de Tejada Oriente. The original plan is delineated with colors and is 77 Omega by 71 Omega centimeters (30.5 by 28.1 inches).

For the Library of the University of Texas.

Very courteously, {signatuare} V. Alessio Robles, Federal District of México, August 22, 1935."

The elements that produced the confusion from 1913 through the 1960s, and which are still causing problems such as Groneman's charges of forgery, can be seen on this map. The topographic map is dated on its secondary title block, and in the Benson collection, as having been made in 1828. The name of José Juan Sánchez Estrada is indicated on the primary title block as being the copyist of the entire composite map. The first part of the title of the Vista on the "Copia del Mapa" is virtually identical to the caption on the Berlandier copy of the Estrada drawing; and the Vista has the signature "Jose Juan Sanchez, 1836, Dibujo José Juan Sánchez, 1836, drew {this}." It is easy to see how, through a careless combination of these elements, the drawings of the Alamo were attributed to José Juan Sánchez Estrada in 1828 (not 1829, as the San Antonio Express had it). No specific reference to José Juan Sánchez Navarro appears anywhere on the map - Nelson's attribution of the map to Navarro is based on its similarity with the plan in the Navarro journal.

The historical circumstances that produced the map are fairly clear. In 1840, Carlos Sánchez Navarro y Ber.in purchased the lands of the Marquesado de Aguayo and added them to the already-huge hacienda of the Sánchez Navarro family.21 The Marques de Aguayo had sold the marquisate to the joint ownership of the British land speculators of Baring Brothers and Company, based in London, and Staples and Company, operating out of Mexico City, in 1825. In 1829 the two companies appointed Dr. James Grant as general manager of the marquisate, under its new name of the "Parras State and Company."22

Although the details of the bizarre manuverings between creditors of the Marques, the British companies, and the government of the state of Coahuila over the next ten years would make a book in its own right, the story has been told by Charles Harris and Vito Alessio Robles.23 Dr. Grant went on to become involved in Federalist politics. He went to Texas, and while fighting for the independence of Texas was killed by the cavalry of General José de Urrea at the battle of Agua Dulce Creek, on March 2, 1836.24 The British companies, fed up with political problems and unable to find a manager of Grant's abilities to replace him, accepted Carlos Sánchez Navarro's offer to buy the Estados de Parras in 1840.25

The "Copia del Mapa" appears to have been made by Sánchez Estrada partly to celebrate the acquisition of the marquisate by the Sánchez Navarro family, and partly as a memorial to the fall of the Alamo and the subsequent loss of Texas, as witnessed by one of the favorite sons of the Sánchez Navarro family, José Juan Sánchez Navarro. The notations on the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras" portion of the "Copia del Mapa" make it clear that the map of the lands between Parras and San Buenaventura was copied from the original plan of the Marquesado de Aguayo prepared in 1828 by S.M.L. Staples of Staples and Company, the co-purchaser of the land. It was included on the "Copia del Mapa" prepared in 1840 by José Juan Sánchez Estrada to show the land of the marquisate purchased by the Sánchez Navarro family in that year. The rest of the "Copia del Mapa" is a composite of several different sections. The various parts of the map and its accompanying tables and other information appear to have been drawn on a sheet of paper and then cut up into a series of squares which were glued to a cloth backing so that it could be folded up without tearing along the folds. The title block for the "Copia del Mapa" was drawn to look as though it had partially peeled up at the time the photostat was made, revealing part of the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras" underneath. At the top of the map is a drawing of an eagle on a prickly-pear cactus, a snake in its beak, the emblem of Mexico - identical in style and details to the same emblem drawn on the first page of the second volume of Sánchez Navarro's ledgers.26 Most of the left half of the map is the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras," with a compass rose and scales in "Leguas Mexicanas," Mexican leagues (each 2.63 miles long) and "Millas Inglesas," English miles. Below the scales is a note, "Nota de Staples: La Administracion de la Laguna este fueron de las limites de este Mapa, al Noroeste: y segun los titulos, tiene 2,200,000 acres Note by Staples: The Administration of Laguna would be outside the limits of this map, to the northwest; according to the titles, it contains 2,200,000 acres." Filling the right half of the Mapa are a series of tables: "Estado que manifiesta los Departamentos de la republica mexicana, su estencion en leguas cuadradas, su poblacion, capitales, la latitud y longitud de esas, y el numero de habitantes que contienen Status of the departments of the Mexican Republic, their extent in square leagues, their population, capitals, their latitude and longitude, and the number of habitants they contain;" "Derrotero Del Saltillo A Otros Puntos Itinerary from Saltillo to Other Points;" and "Derrotero: Distancias que hay de Mexico a varios puntos y de unos puntos a otros de la Republica Itinerary: Distances from Mexico City to various points and from some points to others of the Republic," many of them along routes into Texas, to such locations as Bexar, Nacogdoches, and Goliad. These tables have a note at the bottom: "Estos derroteros y el anterior estado se copiaron de los de cuaderno de la Geografica por el Excelentisimo Señor Don Juan Nepumoceno Almonte These Itineraries and the earlier Status were copied from those of the booklet of Geography by the most excellent Señor Don Juan Nepumoceno Almonte."27 Very similar itineraries, using virtually the same symbols indicating the types of territory crossed, were used in Sánchez Navarro's ledger.28

In the lower right corner is a dedicatory panel, showing a dog leaning against a stone block in which are carved the words, "Jose Juan Sanchez Estrada, . su muy amada Esposa Anna Petra de la Peña, y . sus vien queridos y buenos hijos, Juan, Maria, Mariano, Juan Segunda, Antonio i Manuel José Juan Sánchez Estrada, to his very beloved wife Anna Petra de la Peña, and to his well-loved and good children, Juan, Maria, Mariano, Juan the Second, Antonio and Manuel." Beneath the dog is a ribbon bearing the words "Leal, Fiel i Constant Loyal, Faithful and Constant."29

In the lower left corner is the title block, "Copia del Mapa," as given above. Below the title block, and extending along the bottom of the map from the left edge to the dedicatory panel, are the captions and drawings of the Vista and Plano from which Berlandier's copy and Sánchez Navarro y Peón's and Nelson's enlargements had been made. The drawings as seen in Nelson's enlargement are identical to those included in Sánchez Navarro y Peón's La Guerra, down to the chipped and worn edges along the bottom of the map and the random stains and spots visible on the drawings. The main differences are that the two images are trimmed differently, and the half-tone shading is much coarser in the Sánchez Navarro y Peón copy. The similarities of lighting and the setup of the photograph suggests that, like Nelson sixty years later, Sánchez Navarro y Peón used the photostat in the University of Texas Library as the source for his illustration in La Guerra in 1938.

The captions and indexes for the Alamo Vista and Plano have never been made available in their entirety.30 They are fairly difficult to read in places where the shading on the photostat is dark or slightly out of focus, but with a little effort they can be made out. The original, in full color including the Vista and Plano, would be much easier to read. The complete texts written into the various sections of the Vista and Plano are given below:

***************

On the Vista

Jose Juan Sanchez, 1836, Dibuj?o

José Juan Sánchez, 1836, drew this

To the left of the Plano

Plano Del Fuerte, Su Esplicacion I Algunas Notas.

1. Puerta principal fuí tomada en el dia del asalto por los Señores Coroneles Don Juan Morales y Don José Miñon con cerca de 300 hombres del Batallón activo de San Luis Potosi.

Main gate that was taken on the day of the assault by the Señores Colonels Don Juan Morales and Don José Miñon with about 300 men of the Active Battalion of San Luis Potosí.

2. Cuarto del Oficial de guardia.

Room of the officer of the guard.

3. Deposito de herramientas y maderas, o Maestranza.

Depository of iron tools and timbers, or armaments workshop.

4. Havitaciones de las familias de Oficiales y tropa de la compañia del Alamo de Parras que ocup. el fuerte por muchos años, por lo cual tomó su nombre el mismo fuerte.

Houses of the families of the officers and troops of the Compañia del Alamo de Parras, who occupied the fort for many years, as a result of which the fort took their name.

5. Patio principal o Plaza de armas.

Main patio or parade ground.

6. Hospital en la testera de la sala que est. contra la puerta sin hacer resistencia murió el fanfarron y asesino Santiago Wuy.

Hospital; in the end of the room that is against the gate, the braggart and assassin James Bowie died without resistance.

7. Cocinas.

Kitchens.

8. Cementario.

Cemetery.

9. Iglesia no concluida y destruida parte de su fabrica para aprovecharse del material en la defensa del fuerte que hiso el Señor Coronel Don Domingo de Ugartechea ayudado del de igual Clase Don José Maria Mendoza, mandados ambos por el Señor General Don Perfecto de Cos.

Unfinished church; part of its fabric was destroyed in order to use the material for the defenses of the fort, built by Señor Colonel Don Domingo de Ugartechea assisted by Don José Maria Mendoza of the same rank, both under the orders of Señor General Don Perfecto de Cos.

10. Almacén de polvora.

Powder storeroom.

11 y 12. Almacen de viveres: estas dos piezas y la anterior estavan fuertes y muy vien conservadas.

Storeroom for food supplies; these two rooms and the last one were strong and in very good condition.

13. Cuartel alto con su portal, y corredor: este edificio estava servible y por su construccion y por estar apoyado en la iglesia formaba el caballero alto a la parte principal del fuerte de la cual si el enemigo hubiera echo una segunda linea de defensa, habrian perecido mas soldados de los que perecieron para arrojarlo de ella.

Two-story barracks with its gate and hallway; this building was in reasonable condition; because of its construction and because it was supported by the church, it formed a high "cavalier" position in the most important part of the fort - if the enemy had made a second line of defense here, more soldiers would have died than those that died as a result of attacking it.

14. Calabozo. Jail.

15. Patio para caballos. Courtyard for horses.

16. Corral y comunes. Corral and latrines.

17. Bateria llamada de Teran, por los mejicanos,31 al pie de ella murió como valiente el gefe

de los Colonos llamada Trawiz.

Battery called "de Terán" by the Mexicans, at the foot of which Travis, the

leader of the colonists, died valiantly.

18. Bateria llamada de Condelles32 por este punto asalto el Señor General Cos con 200 hombres de Aldama y 100 de San Luis, logrando penetrar por la azotea de la esquina 4 y por las posternas señaladas con los numeros 26; esta columna fue la primera en el asalto.

Battery called "de Condelles;" at this point Señor General Cos attacked with 200 men of the Aldama and 100 of San Luis, managing to get in through the roof of the corner (number 4) and by the postern doors marked with the number 26; this column was the first in the attack.

19. Esplanada de una bateria que se formó en lo alto de la iglesia con el nombre de Cos.33

Ramp of a battery with the name of "Cos" that was built at the top of the church.

Los numeros 20 manifiestan un foso y banqueta interior con que los colonos quisieron reforzar lo interior del fuerte y antes lo devilitaron.

The numbers "20" indicate an interior ditch and banquette with which the colonists sought to reinforce the interior of the fort, but instead weakened it.

21. Fosos echas por los mismos para libertarse metiendose dentro de las casas de las granadas y de las valas de artilleria.

Ditches made by the same colonists inside the houses in order to protected themselves from injury by the grenades and artillery shot.

22. Empalizadas semicirculares.

Semicircular palisades.

23. Foso que empezaron y no pudieron concluir.

Ditch that was begun, but they the colonists were unable to complete it.

24. Por este punto intentaron la fuga algunos colonos.

From this point some colonists attempted to escape.

25. Por los puntos señalados con estos numeros atacaron y entraron al fuerte los Señores Coroneles Duque y Romero mandados por el Señor Coronel Amador con cerca de 500 hombres de Zapadores y Toluca, Duque fué herido de metrallas antes de entrar. (*).34

At the points indicated by this number, the Señores Colonels Duque and Romero, commanded by Señor Colonel Amador, with about 500 men of the Zapadores and Toluca, attacked and entered the fort; Duque was wounded by shrapnel before entering.

26. Already mentioned as the posterns on the north end of the west wall in no. 18.

Beneath the title block

(*) 27. Pozo echo por los colonos para provarse de agua el cual no los surtió bien efecto pues sacaron ó alcansaron una imbebible.

Well made by the colonists to provide water; the which did not supply them to good effect because they obtained undrinkable water.

28. tres piezas que se les desmontaron antes del asalto.

Three pieces of cannon that had been dismounted before the attack.

29. espaldon echo por los colonos para defendar la puerta.

Breastworks made by the colonists for the defense of the gate.

El Capitan de los colonos que ocupa el Alamo el 13 de Diciembre de 1835 se llamaba Eduardo Wurlinson,35 con 1100 hombres. El Excelentisimo Señor Don Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna General de Division y Presidente de la Republica Mexicana con el ejercito de su mando ocupo la ciudad de Bejar en 23 de febrero de 1835 y mando en persona el asalto del Alamo; en tomar el cual hubo la perdida siguiente, de las cinco a las 6 de la mañana del 6 de marzo, muertos, 11 oficiales y 110 de tropa, heridos, 2 jefes 17 oficiales y 247 de tropa. Muertos del enemigo las que habia 257, quitadas muchas armas y muchas municiones. El Señor Coronel Don Juan Andrade destruyo completamente el referida fuerte . fines de Abril del mismo año (aciago y manquado) de 1836.

The captain of the colonists who occupied the Alamo on the 13th of December, 1835, was named Edward Burleson, with 1100 men. The most excellent Señor Don Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, General of the Division and President of the Mexican Republic, with the army under his command occupied the city of Bexar on the 23rd of February, 1835, and commanded in person the assault of the Alamo; taking it from 5 to 6 in the morning of the 6th of March, resulted in the following losses: killed, 11 officers and 110 troops, wounded, 2 senior officers, 17 officers and 247 troops. Enemy dead were 257, leaving many arms and munitions. The Señor Colonel Don Juan Andrade completely destroyed the fort being discussed at the end of April of the same fateful and maimed year of 1836.

Above the Vista

Vista del Fuerte de San Antonio de Valero, llamado comunmente del Alamo, tomada desde la azotea de la casa de Beramendi cituada en la Ciudad de Bejar:36 dicho fuerte se levantó por los años de 1722 de orden del Excelentisimo Señor Virrey Don Baltazar de Zuñiga, Marques de Valero: en 1812 fué ocupado por los aventuros Anglo-Americanos, mandados por el Coronel Don Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara: en 1813, en la Batalla de Medina, lo recuperó el Señor Brigadier Arredondo: en 1835 el 13 de Diziembre, despues de 55 dias de hacian? de defenza, lo ocuparon por capitulacion los reveldes colonos de Texas: y el 6 de marzo de 1836 lo tomaron por asalto las tropas Mexicanas.

View of the Fort of San Antonio de Valero, commonly called the Alamo, made from the roof of the Veramendi house situated in the City of Bejar: the said fort was built in the years sic of 1722 by order of the most excellent Señor Viceroy Don Baltazar de Zuñiga, Marques of Valero; en 1812 it was occupied by Anglo-American adventurers commanded by Colonel Don Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara: in 1813, at the Battle of the Medina, Señor Brigadier Arredondo recovered it: in 1835, the 13th of December, after 55 days of defense, the rebel colonists of Texas occupied it by capitulation: and the 6th of March, 1836, Mexican troops took it by assault.

Next to the Plano

Tengase presente, ante todo, que este Fuerte se construyo solo con el fin de tener sugetas a las velicosa Tribus salvajes que poblaban . Texas, para servir de punto de apoyo y de escala . los establecimientos, como Nacogdoches, fundados por los Españoles al norte de la provincia: y para asegurarse de la obediencia de las Miciones llamadas de San José, la Espada y Concepcion, que de los Salvajes de paz se establecieron . sus immediaciones.

La ciudad de San Fernando de Bejar, que despues se llamó de San Antonio fue construida al abrigo del Fuerte al Oeste distante 1000 varas en 1732, de orden del Excelentissimo Señor Virrey Don Juan de Acuña, Marques de Casa-fuerte.

Bear in mind, before all, that this fort was constructed specifically with the purpose of holding subject the bellicose and savage tribes that lived in Texas, in order to serve as a point of support and supply to the settlements such as Nacogdoches, founded by the Spanish at the north of the province: and in order to assure in obedience to the Missions named San José, la Espada and Concepción, the peaceful savages settled in their immediate area.

The city of San Fernando de Bejar, that later was called San Antonio, was constructed under the protection of the fort to the west a distance of 1000 varas 2,778 feet in 1732, by order of the most excellent Señor Viceroy Don Juan de Acuña, Marques de Casafuerte.37

Although the plan of the Alamo is very inaccurate, the details seem carefully noted. The information included on the plan strongly suggests that José Juan spent some time examining the defenses of the Alamo after it fell on March 6, 1836, perhaps making notes of his observations, but did not make anything more than a very rough sketch of the plan of the fort while he was actually there; if so, the sketch plan did not effectively portray the Alamo, and the apparent differences between it and his sketch of the Vista (or his inability to remember what he meant by this or that squiggle) confused him more rather than helping him. The Vista may be based on a very quick and rough view made, as its caption says, from the roof of the Veramendi house in 1836, considerably revised by memory in 1840 when he made the final draft for the "Copia del Mapa."

Sánchez Estrada appears to have been very careful about alloting credit - the secondary title block appears to be the equivalent of a credit line for the originals of the "Mapa de los Estados de Parras" and the small note at the bottom of the tables indicates the source for these as a book by Juan Almonte. The note "José Juan Sánchez, 1836, Dibuj?o" written in the lower right corner of the Vista, is the credit line for at least this drawing, if not both the Vista and Plano, but it is unclear whether the delineator referred to was José Juan Sánchez Navarro or José Juan Sánchez Estrada. The Plano, however, clearly derives from the Fuerte plan in José Juan Sánchez Navarro's journal, and the Vista clearly derives from the Plano, in that its features in elevation match the features shown in plan on the Plano, as demonstrated by the artist and Alamo historian Craig Covner.38 The text of the index for the Plano is very similar to the index to the Fuerte plan in the journal. There is no reason to doubt that Sánchez Navarro's diagram was the basis for the Vista and Plano.

As we have seen, the origin and the reason for existence of the "Copia del Mapa" is fairly clear, and its provenance, although broken between 1840 and 1935, is effectively beyond question since the document was photostatted by Vito Alessio Robles (the acknowledged expert on the history of northern Mexico and a man beyond any possible accusation of duplicity) while he was working on his histories of Coahuila and Texas. What is not clear is the reason for the presence of a plan and elevation of the Alamo on the Mapa. Why would a plan and captions taken from José Juan Sánchez Navarro's journal and a view of the Alamo in 1836, drawn by José Juan Sánchez, be included in a composite map of property acquired by the Sánchez Navarro family in 1840? If it was to be a memorial to the war in Texas and the participation of Sánchez Navarro, as suggested above, why wasn't Sánchez Navarro mentioned anywhere on the map? In order to answer this, we need to know a little more about the two José Juans involved.

At the time of the purchase of the old Marquisate of Aguayo in 1840, José Juan Sánchez Navarro was 47 years old, and one of the most prominent public figures of the family. He was born in 1793, and as a boy had been sent to Mexico City for an education, but had instead joined the army. He became a follower of Hidalgo and joined the Insurgentes, rising to the rank of captain in the Insurgent army while still in his teens, and became an aide to Ignacio Allende, leader of the independence movement. He was captured in the Insurgente defeat at the Wells of Baj.n in 1811, and scheduled to be shot, but was given amnesty through the political influence of his family. In 1821, as a lieutenant of militia in Saltillo, he was one of the leaders of a planned coup intended to commit the town and the province to the support of the Plan of Iguala, the independence movement that eventually separated Mexico from the Spanish Empire. During the 1820s, his military career kept him in Coahuila and Texas, and a large number of his official letters and orders are in the Bexar Archives.39

In 1831, Sánchez Navarro became adjutant inspector for Nuevo León and Tamaulípas, and continued in that position through the Texas Revolution. As a result of his good service during the war in Texas, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned to duty on the northern frontier, where he became reknown as an Indian fighter. In 1842 he lead a relief column into the Sánchez Navarro ranchlands to rescue the fortified ranchhouse at Patos from a Comanche attack. During the Mexican War he was a staff officer at Santa Anna's headquarters. By the end of the war, he was a general, and in 1848 he became the commandant general of Coahuila, the rank and post he held until his death in 1849.40

Who was José Juan Sánchez Estrada? Schoelwer sums up the general confusion about this person with the conclusion that "while Sánchez Estrada may have participated in boundary commissions named after Texas became part of the United States, he does not seem to have been a member of the Mier y Ter.n party of 1828-1829."41 The solution to the difficulty of too many José Juans, however, is very straightforward. José Juan Sánchez Navarro was the son of José Antonio Sánchez Navarro and his wife, Juana Josefa Estrada. In other words, José Juan's full name was José Juan Sánchez Navarro y Estrada - that is, Sánchez Navarro and Sánchez Estrada are the same person. 42 Among his other military assignments, in 1828, when he was still a captain, Sánchez Navarro y Estrada was assigned to command the escort of General Manuel de Mier y Ter.n during Ter.n's tour of Texas - he was the José Juan Sánchez Estrada of the boundary commission mentioned on Berlandier's traced copy of his view of the Alamo. The documentation of José Juan's participation in the border commission is extensive. Charles Harris, for example, cites five letters between various members of the family discussing the topic in 1828, all to be found in the Sánchez Navarro Papers in the archives of the Center for American Studies, University of Texas at Austin..43 Harris tells us that José Juan Sánchez Navarro married Ana Petra de la Peña,44 the name shown on the dedicatory panel of the "Copia del Mapa," listed as the beloved wife of José Juan Sánchez Estrada.

There can be no doubt. The Berlandier caption was correct all along: the Vista of the Alamo was indeed drawn by José Juan Sánchez (Navarro y) Estrada, who was indeed a prominent citizen and who had accompanied the boundary commission in 1828 and 1829. However, José Juan drew the Vista, not in 1828 or 1829, although his frequent presence in Bexar during the 1820s would have made that perfectly possible, but rather in 1840, at the time of the acquisition of the old Marquesado of Aguayo by his family. According to the accompanying note, it was based on a sketch he made in 1836 from the roof of the Veramendi house, and the Plano accompanying it was derived from the Fuerte plan, somewhat changed from its original version in the ledgers.

Groneman's accusations of forgery make little sense in light of this context for the plans and Vista and the journal accompanying them. It is, of course, possible that they are all forgeries, but this would have to include the letters in the Sánchez Navarro papers and the Bexar Archives. With so many lines of evidence supporting the existence of the drawings and journal, copied so often over the years from the 1840s or earlier to the 1930s when they were finally published, it would take an intricate conspiracy at work beginning in the 1840s to create the record we have seen - and for what purpose? No particular end would have been served by such a series of forgeries. Occam's razor indicates that we should accept the simplest explanation: José Juan Sánchez Navarro y Estrada actually wrote and drew all these documents, plans, and Vista in 1836-1847.

–James E. Ivey, June 2000

1 Susan Prendergast Schoelwer,

"The Artist's Alamo: A Reappraisal of Pictorial Evidence, 1836-1850," Southwestern

Historical Quarterly, 91(April, 1988)4:416; Charles H. Harris III, A

Mexican Family Empire: The Latifundio of the Sánchez Navarros, 1765-1867

(Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975), p. 284; Helen Hunnicut, "A Mexican

View of the Texas War," The Library Chronicle of the University of Texas

4(Summer, 1951)2:59-74; Vicente Filisola, Memoirs for the History of the

War In Texas, Wallace Woolsey, tr. (Austin: Eaking Press, 1987), vol.

2, pp. 90-96; apparently there is no independent documentation of Sánchez

Navarro's presence at the battle of the Alamo in 1836, beyond his own statements.

2Carlos Sánchez Navarro y Peón, La Guerra de Tejas - Memorias de un Soldado (Mexico City: Editorial Polis, 1938). The Sánchez Navarro journal entries are on pp. 91-151.

3José Juan was Carlos Sánchez Navarro y Peón's great great great grand nephew. Carlos was descended from Manuel Francisco Sánchez Navarro, while José Juan was the son of Manuel Francisco's younger brother José Antonio; Harris, Sanchez Navarros, genealogical chart after p. 402. Carlos was one of the three members of the Sanchez Navarro family who aided Charles Harris in his research for A Mexican Family Empire; Harris, Sanchez Navarros, p. xiii.

4José Juan Sánchez Navarro, "Ayudantía de Inspección de Nuevo León y Tamaulípas," 1831-1839 (with journal entries through 1847), 2 vols., Sánchez Navarro (José Juan) Papers, box 2G146, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. The journal is not obvious in the ledgers; they are a mixture of tables of data, lists of documents, statements about pending business, and discussions of problems being encountered, in addition to the journal; see Helen Hunnicut, "A Mexican View of the Texas War," The Library Chronicle of the University of Texas 4(Summer, 1951)2:appendix I, "Contents of Sánchez Index," pp. 67-70.

5Lon Tinkle, 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1958), p. 249; Tinkle's description of the document was somewhat faulty; he discussed the "discovery in 1936 of a private record kept inside ledger books by Maurice Sánchez, during his years as a Mexican border official at Matamoros (1833-1849)...."

6Sánchez Navarro, "Inspección," vol. 2, folios i(verso)-ii(verso). Folio i is the first flyleaf of the second volume of the ledger, and the plan overlaps onto the front of the second flyleaf, folio ii. The index caption for the lettered points on the map fills the rest of the front of the second flyleaf, and continues on the back of it; see Hunnicut, "Mexican View," pp. 59-74.

7The few sketched details of the plan of the fort are fairly similar to the "Correct View of Fort Defiance Goliad," by Adjutant Joseph M. Chadwick, 1836, a copy of which is bound inside the back cover of Kathryn Stoner O'Connor, The Presidio La Bahía del Espiritu Santo de Zuniga (Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co., 1966).

8Sánchez Navarro y Peón, La Guerra de Tejas; the Vista and Plano follows p. 96, and the Fuerte follows p. 152.

9Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," p. 416.

10Ron Tyler, ed., New Handbook of Texas (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1996), vol. 1, p. 500; Jean Louis Berlandier, Journey to Mexico during the Years 1826 to 1834, Sheila M. Ohlendorf, Josette Bigelow, and Mary M. Standifer, trans. (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1980).

11Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," pp. 414-15, 417, figure 5 caption and n. 18; Berlandier sketchbook, "Planos topograficos," series C, vol. 1, p. 229, MSS S-300, vol. 7, Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

12L. Robert Ables, "The Second Battle for the Alamo," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 70(January, 1967)3:372-413; also Colquitt's Message.

13Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," pp. 414, n. 15, 419; San Antonio Express, "How the Alamo Really Looked: Earliest Pictures that Tend to Clear Up the Mystery," September 28, 1913.

14Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," p. 420 and fig. 5.

15Bill Groneman, Defense of a Legend: Crockett and the de la Peña Diary (Plano, Texas: Republic of Texas Press, 1994); José Enrique de la Peña, With Santa Anna in Texas - A Personal Narrative of the Revolution by José Enrique de la Peña, Carmen Perry, trans. and ed. (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1975). This was essentially a translation of J. Sánchez Garza's transcript of Peña's journal, La Rebelion de Texas - Manuscrito Inedito de 1836 por un Oficial de Santa Anna (Mexico City: A. Frank de Sánchez, 1955).

16Groneman, Defense of a Legend, pp. 95-99, 101-05.

17Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," p. 419.

18George Nelson, The Alamo: An Illustrated History, (Dry Frio Canyon, Texas: Aldine Press, 1998), p. 22.

19The appearance of Nelson's copy of the Vista and Plano in Nelson's book prompted me to contact Adan Benavides of the BLAC, asking him if he knew of such a map. He in turn asked archivist Jane Garner, and she suggested that I might be looking for a map in the collection that existed only as a photostatic copy donated to UT Austin by Vito Alessio Robles in 1935. At this point I contacted George Nelson about the source of his photograph of the Vista and Plano. He generously sent me a xerox of a portion of the larger map on which they were included, with a note that it was from the BLAC, and that "it is from a B&W phot. of a large `Mapa de la Estados de Parras;'"George Nelson to James Ivey, January 19, 2000, in the collection of the author. Michael Hironymous, Head of Public Services at the BLAC, made xeroxes of the photostat and sent them to me, which allowed me to confirm that the Alessio Robles photostat was the source of Nelson's pictures, and to transcribe most of the captions and indexes. Michael also arranged for me to get the photographic copies used in this article. Thanks to all these people for their help in solving this intriguing puzzle of Texas history.

20The photostat of the "Copia del Mapa" is listed in the Benson Latin American Collection catalog under the title of the map portion, "Mapa de los Estados de Parras," MAP M972.13 1828a2. The catalog card says "Alvarez, Manuel. Mapa de los Estados de Parras. Detailed relief map of the area in Coahuila from the original of S.M.L. Staples. Contains in addition: Plano del fuerte, vista del Fuerte de Sn. Antonio de Valero, Derrotero, y los Departamentos Mexicanos. Positive photostat. 21 x 38 cm; 8º x 15 inches." Looking in the catalog under "San Antonio de Valero, fuerte de" would also direct a researcher to this map.

21Harris, Sánchez Navarros, pp. 162-167. Harris made use of the large collection of documents dealing with the Sánchez Navarro family and ranch in the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, the Sánchez Navarro Papers; Harris, Sanchez Navarros, p. xvi.

22Harris, Sanchez Navarros, pp. 163-64; a better translation would be the "Parras Estate and Company."

23Harris, Sanchez Navarros, pp. 162-67; Vito Alessio Robles, Coahuila y Texas, desde la consumación de la independencia hasta el tratado de paz de Guadalupe Hidalgo (Mexico City: Antigua Libreria Robredo, 1945-1946), vol. 1, pp. 142-44, vol. 2, pp. 250-265; Alessio Robles, Coahuila y Texas en la época colonial (Mexico City: Editorial Cultura, 1938), pp. 508-09.

24Hardin, Texas Iliad, pp. 107, 158-59. From the Texas side, Grant was said to have owned a large estate in Coahuila called the Hacienda of Furnaces, at Parras, but that he lost it through political manuvering by his enemies; New Handbook of Texas, vol. 3, p. 282. This appears to be a distortion of the actuality, that he was only the manager of the Marquesado de Aguayo.

25Harris, Sanchez Navarros, p. 166.

26Sánchez Navarro, "Ayudantía de Inspección," vol. 2, f. ___ Cite, when I get the xeroxes.

27I am uncertain to which book Sanchez y Estrada refers in this line. However, portions of the Derrotero del Saltillo are very similar to the "Itinerary from Nachitoches to Mexico City by way of Texas," in Juan N. Almonte, Noticia Estadistica sobre Texas (Mexico: 1835). Carlos Castañeda translated this booklet in "Statistical Report on Texas," Texas State Historical Quarterly, 28:177-222; and a different translation was done by Wallace Woolsey in Filisola, History, vol.2, pp. 261-287. Almonte was later a Colonel under Santa Anna at the Battle of the Alamo, and fought at San Jacinto where he was taken prisoner; Hardin, Texas Iliad, pp. 113, 131, 213.

28Sánchez Navarro, "Ayudantía de Inspección," vol. 2, ff.___.

29Just above and to the right of the carved block, the number "1/510342" is written. This looks like a catalog or accession number.

30The index included in Sánchez Garza, La Rebelion, pp. 61-62, is very abbreviated, changes some phrases, and leaves out part of the indexes and most of the captions.

31This battery was named after General Manuel de Mier y Ter.n, commandant general of the Eastern Interior Provinces. The phrase "por los mejicanos" indicates that this and the following battery names are nicknames placed on them by the Mexican troops, not by the Texans. These names may have been applied at the time the batteries were built by Colonel Ugartechea during the fortification of the Alamo in October and November, 1835 (see no. 9, above).

32This battery was named after Colonel Nicholas de Condelle.

33This battery was named after General Martín Perfecto de Cos.

34The index up to this point was printed in Sánchez Navarro y Peón, La Guerra, between pp. 96 and 97. The text of the index on the plan, presented here, differs in a number of places from the transcription provided by Sánchez Garza, La Rebelion de Texas, pp. 61-62, both in the text and in the location of numbers on the plan. The symbol (*) indicates that the index left off here and continued where this same mark appears again, to the left of this block of text on the "Copia del Mapa."

35This is General Edward Burleson, who accepted Cos's surrender and ended the Battle of Bexar on December 10, 1835; Hardin, Texas Iliad, p. 90.

36The text copied onto the Berlandier drawing of the Vista is the first phrase to this point, with some minor changes.

37The remark in the caption above the Vista that Valero was built in 1722 by order of the Marques de Valero, in conjunction with this caption next to the Plano, indicates that the author of this index thought that, rather than being an ex-mission, the Alamo was the Presidio San Antonio, created by order of the Marques de Valero and moved to its final site on Military Plaza in 1722.

38Craig R. Covner, "Before 1850: A New Look at the Alamo Through Art and Imagery," The Alamo Journal, 70(March, 1990):3-10.

39Carlos Castañeda, The Fight for Freedom, 1810-1836, vol. 6 of Our Catholic Heritage in Texas (Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones Company, 1950), pp. 10, 32-34; Harris, Sanchez Navarros, pp. 136, 143, Adan Benavides, The Béxar Archives (1717-1836) - A Name Guide (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp. 932-34.

40Harris, Sanchez Navarros, pp. 193, 284, 288, 290.

41Schoelwer, "The Artist's Alamo," p. 420.

42Harris, Sanchez Navarros, genealogical chart following p. 402.

43Harris, Sanchez Navarro, p. 284.

44Harris, Sanchez Navarros, genealogical chart following p. 402. It would be interesting if José Juan was therefore related to José Enrique de la Peña, the other well-known Mexican eyewitness chronicler of the Battle of the Alamo.

![]()