![]()

|

Alamo

Sourcebook 1836 Tim & Terry

Todish

with illustrator, Ted Spring |

|

|

Brothers Tim and Terry Todish have compiled a

comprehensive guide to the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. It has become

a best seller among Alamo enthusiasts and history buffs alike. Contributing

Editor, Robert L. Durham conducts this online interview.

|

||

ADP: You have a short biography at the end of the book, but please provide an update, telling what you've been doing since the book was written.

Tim: I retired from the Grand Rapids Police Department in June of 1997, and our book was published in March of 1998. The next year or so I spent working on the History Channel series Frontier: Legends of the Old Northwest. My official title was Technical Advisor, but I performed a wide variety of duties in addition to my technical services. For example, I participated as a reenactor/extra myself, coordinated other reenactors, and took most of the still photos. The series was produced and directed by my good friend Gary Foreman, who is also an Alamo buff.

Ted: I am a supervisor and lead driver for Allied Waste Control, operating street sweeper trucks (basically huge vacuum cleaners) for Oklahoma City.

Terry: I'm still working for Compulit, Inc., which builds databases and provides a full range of litigation support services to law firms all over the country. As a matter of fact, we've worked on several high profile cases lately. Also, I've gone back to school part time working on a Computer Information Systems degree.

ADP: Do you have any future books in the works at this time?

Tim: Currently I am working on an illustrated and footnoted edition of Robert Rogers' French & Indian War Journals. I am doing the footnoting, and noted artist & historian Gary Zaboly, from New York City, is doing the illustrations. Readers may already be familiar with Gary's work, as he illustrated Steve Hardin's Texian Iliad, as well as Alan Huffines' Blood of Noble Men. Gary has also painted some of the panels for the new "Wall of History" at the Alamo.

Ted: I am working on an illustrated book on the Texas Rangers from 1836 to 1890, the heyday of the Rangers. My book will contain illustrations of the guns, holsters, packs, saddles, and clothing used by the Rangers, plus anecdotal information. When completed, it will be a source book on the Texas Rangers.

Terry: I have three projects that I'm working on that I hope to have published or produced in some manner:

A. I'm working on a "Guide to 18th Century Movies", which will probably take the form of a booklet or pamphlet. It's sort of a video guide and series of essays for reenactors and history buffs to use when the video store is out of "Debbie Does Valley Forge" or whatever. I want to limit it to about 25 titles, so it will probably turn into a series.

B. I'm also working on a project that may become a pamphlet/booklet, perhaps a magazine article, and maybe something else. It's an in depth study of Benedict Arnold's raid on New London and Groton, CT, in 1781, and especially the Battle of Ft. Griswold in Groton. It's a fascinating but little known aspect of the Revolutionary War with some fascinating unsolved mysteries - kind of like the Alamo!

C. My major project is a book length biography of John Stark. Although he was a major figure in Rogers' Rangers during the French and Indian War and played a pivotal role in the American Revolution, there's only been one biography of him written, and it was limited to 500 copies. So hopefully I'll have the first mainstream biography of him ever written.

ADP: When, and how, did you first become interested in the story of the Alamo?

Tim: Like so many people from my era, I became interested in the Alamo when the Walt Disney series Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier first aired on national television. I also remember vividly being taken to the drive-in by my parents to see The Last Command when it was first released. By the time John Wayne's The Alamo came out, I was already hooked.

Ted: My first exposure came upon watching Fess Parker swinging his long rifle, defending the Alamo in Disney's final installment. It was a hard pill to swallow for any youngster of that time, wearing a coonskin cap, to think that Davy Crockett and Georgie Russell could have died anywhere, let alone on the ramp of an adobe mission in San Antonio, Texas

My original interest began in 1960, when I was ten years old. My dad and I stood in a theater line in Burlington, Vermont for an hour and a half to see John Wayne's The Alamo blockbuster.

Then, I was stationed at Fort Sam Houston, in San Antonio, for twenty weeks of medic training when I was in the U. S. Army, and visited the Alamo quite often. Since then, I have examined everything written or illustrated about the Alamo that I could find. Through the years, I have always been acutely interested in any publication that anybody did on the Alamo. I felt that most of the Alamo illustrations were poor and did not accurately represent what the participants looked or dressed like, and decided that there weren't too many people who had any idea how they really looked. Until the mid 1990s, research by the Wayne movie production team had been the best up to that date, and his uniforming and costuming, and the set (although smaller than the actual Alamo compound) was a good representation.

I think every country has its heroes. Every British or English schoolboy knows of the stand of the 24th Regiment of Foot at Rorke's Drift during the Zulu War. I think every Australian child is well aware of the landing at Gallipoli during the First World War. It is certain that for every child who grew up in the fifties here in America, the story of the Alamo is as well known to us. Movies like The Last Command, the Disney production of Davy Crockett, and the release of John Wayne's The Alamo have made this moment in American history something that all Americans are proud of. Certainly, it was the greatest moment in Texas history.

I've also wondered about myself, being a combat veteran of over two years, involved with heavy fighting against the North Vietnamese Army in the mid 1960s [Ted served in the U. S. Army, 1st/61st Light Assault Infantry in the northern I Corps area], if I would have had the courage to cross that famous line in the sand. An important message to be learned from the Alamo is that freedom is not free. The price paid by the 187-odd men on that cold March morning, to me is immeasurable. I will always live my life in total awe of their resolve to stick it out to the end.

|

|

The Michigan Contigent to the Alamo Terry Toddish (2nd from the right) and Tim Toddish (far right) participated in the Alamo festivities last March at Casa de Navarro in San Antonio. Photo courtesy Charles Lara |

Terry: I'm not really sure how and when I first became interested in the Alamo itself, but I do remember seeing John Wayne's THE ALAMO when I was about 4 or 5 years old. I'm pretty sure it's the first movie I saw at a theater, and I not only remember it, I remember the cartoon they showed with it. It was a Bugs Bunny cartoon. I know I watched the Disney series when I was growing up, but the first real serious interest came when I was in the seventh or eighth grade. I read everything I could find on the Alamo (Tinkle, Myers, Lord, Warren, "We Were There..."), and I even built a diorama for a history class. I used an Alamo play set I'd gotten for Christmas a few years before, supplemented with "adobe" buildings made from modeling clay.

After that, interest waned somewhat until we started making plans for our first trip to the Alamo in 1990. It's been a serious passion ever since.

ADP: You all have a background in historical reenacting. Describe what influence your experiences in reenacting had in your perception of the Alamo siege and battle.

Tim: There is far more to reenacting than just a bunch of adults dressing up and playing "cowboys and Indians." A serious reenactor has to research all of the aspects of his period, not just those that are of primary interest to him. In his search for knowledge, he must study everything about the period, and not just the military aspects. The reenactor must be critical, and not just accept everything that is written as the truth.

Reenactors tend to be interested in more of the mundane details than most academic historians. While an in depth knowledge of the styles of clothing worn, the types of food eaten, and how the weapons actually worked is not necessarily essential to writing good history, it can add a very interesting and personal dimension to an already good story. No one, reenactors included, can recreate any historical era or event with 100% accuracy, but "living" history as closely as possible does give a writer one more tool to improve his finished product.

Ted: I didn't use my reenacting experience because, as a combat veteran, I've seen the real thing. I think that although the uniforms have changed and we've gone from the Baker rifle and U. S. Common musket to the M16 rifle, the courage that's demanded from any soldier in "do or die" situations will always come from that same place inside the man. I think Jefferson was right, that the tree of Liberty will surely, throughout history, require constant watering with the blood of patriots.

Tim: Ted is a veteran of the Siege of Khe Sahn, so he knows what it is like to be on the "inside" during an extended siege. There were a number of times during our discussions when he brought up points that I am sure are timeless.

Terry: Probably one of the biggest advantages reenacting brings to historical research is the understanding of material culture, and in our case it's no exception. Knowing firsthand how the various weapons work, how they feel, what the differences are between rifles and muskets, and so on all help understand certain aspects of the Alamo story.

Also, you get insights into clothing and accoutrements. It's probably no big revelation to most serious Alamo buffs, but I'm sure many of the general reading public still picture most of the defenders in buckskins and coonskin caps. And all other reasons for not being dressed that way aside, reenactors know that buckskins are hot in warm weather, cold in cold weather, and simply awful when wet. It's not that they weren't worn at all, but they weren't that common, for good reason.

Portraying light troops, even of a different era, and seeing how different kinds of troops work in the field, also gives a better understanding of Santa Anna's deployment.

ADP: I had an opportunity to speak with John Bryant, a feature writer for Alamo de Parras, during the Alamo High Holy Days this spring. He told me some stories of reenacting the Mexican siege, and pre-dawn attack, at Alamo Village in Brackettville. Two things he talked about were the problems they encountered pushing a cannon to the top of the ramp in the rear of the chapel, and the difficulties in loading & firing their rifles in the darkness. He said that, after the fight was over, there was gunpowder spilled everywhere on the breastworks because it was so difficult to hurriedly load the rifles in the dark, in a near-combat situation. Have you had any reenacting experiences that gave a greater appreciation for what it must have been like for the Mexican soldados and Texian defenders back in 1836?

Tim: Being a reenactor helps you to understand the hardships and the limits that the people of the time faced. It helps you to keep from making judgments based solely on our modern knowledge and technology.

Knowing what it is like to be out in all kinds of weather, wearing period clothing, and using historically correct weapons and equipment. Reenacting on the actual ground where historical events really took place. Sharing experiences and picking the brains of my fellow reenactors. All of these are extremely valuable to me when I sit down and begin to write about an historical subject.

Having been both a soldier in the ranks, and an officer commanding fairly large 18th century armies, I have a real appreciation for how important it was for the soldiers to be properly drilled in their "exercises." While I have never had to do it in the actual heat of battle, I also have experienced just how challenging it can be to give the right orders at the right time to get your troops to do what you want them to do! Many things that seem so easy in theory or on paper, are much more difficult in real life.

Terry: One recent experience, although it didn't come in time for the book, really helped me understand both sides a little better. Last summer Tim and Todd Harburn and I took part as rankers in a reenactment of the Battle of Mackinaw Island during the War of 1812. Usually all of us portray officers when we do F&I, so this was an unusual opportunity to see a "grunt's eye" view of a battle. What really stands out in my mind is how routine the fighting became. We weren't watching the progress of the battle, or moving troops, or checking events against the scenario, we were just loading and firing and loading and firing and loading and firing. You get the picture. Every once in a while I would "come to" and realize I was part of a reenactment, but then the sergeant or officer would start giving firing commands again, and I'd be back at it. I think we knew when writing about the battle that that's how it often is, but I hadn't personally felt it in a long time.

ADP: With so many people involved in putting The Alamo Sourcebook together, did you experience any unique problems in coordination?

Tim: Actually, everything went quite smoothly. We had a clear cut plan of who was going to do what, and it was fairly easy for everyone to complete their individual assignments. We gave Ted an idea of what we wanted in the way of illustrations, but he also came up with many good ideas of his own. Terry and I live near each other, so we traded drafts of our work and held frequent discussions to make sure that our efforts were compatible with one another. I was responsible for putting everything together to give the whole manuscript a consistent look, and it really was not a difficult job because of the way we had planned it beforehand.

Ted: I drew the Alamo book for the Todish brothers as a labor of love, for them and a firm desire for people to finally see this the way it really was, not the way so many wish it was.

Terry: I don't remember any particular problems. Tim did most of the coordinating, and at least from my perspective, he did a fine job.

ADP: In the writing of The Alamo Sourcebook, did each of you write his own chapters, or did you collaborate on chapters?

Tim: Although we were constantly sharing ideas, when it came to the actual writing, Terry and I both completed our own assignments. Here is the breakdown of how we did it: Tim: Introductory material, Preface, Acknowledgments (with input from Terry & Ted), Chapters 2, 4, 6, 7 (with input from Terry), 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 (Music Section), the de la Pena sidebar, and the Bibliography (with input from Terry & Ted). Terry: Chapters 1, 3, 5, 7 (assisted Tim), 8, 16 (Movies Section), 17, and all sidebars except the one on de la Peña.

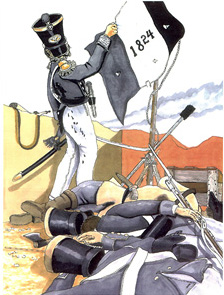

THE DEATH OF TORRES by Ted Spring |

Terry: We did some of both. Most of the time we wrote our sections separately, then passed the section on for review to make sure there were no serious contradictions or problems. When it came to the actual siege and battle, Tim and I wrote that together. He did a first cut, then I added to it, and we refined it so that we were both satisfied This approach allowed us both to have our "voices" come through. I don't know how obvious it is, but Tim and I do have somewhat different styles, and so we were able to write as we felt most comfortable without trying to "sound" like each other. ADP: Were there any portions of the book you disagreed about and, if you did, how did you resolve your differences to decide what the final book would look like? Tim: I really cannot recall any disagreements. We decided right from the beginning what we wanted the book to be—a true and balanced picture of the Siege of the Alamo and the events surrounding it. We also wanted to at least introduce the readers to the uniforms, equipment, and some of the lore that surrounds the Alamo. All the time that we were writing, we kept focused on our goal. We did of course, at times, have to discuss how to handle different aspects of the story, as well as conflicting "evidence," but it was always done in a positive manner. Ted: Due to the fact that it was a project being entered into by three very like-minded, close friends, in the entire five years the project took us, I can never recall, nor were there, any arguments, as it was a dedicated project and a labor of love for all of us. I must also point out that many others provided vast amounts of historical input for the text and for the artwork, and every good thing we got from our helpers, we certainly and immediately utilized. |

Terry: We didn't have many disagreements, and where we did disagree on things we simply presented all sides and acknowledged there was more than one possibility.

Probably the one area I have a real disagreement, not only with Tim, but also with most Alamo historians, is with the surrender/capture/execution stories. Without going into great detail here, I'll just say that I have a hunch everyone went down fighting because I don't think anyone was given an opportunity to be captured or surrender -- later stories aside. But I know a lot of serious researchers disagree, and they deserve their due. And that's basically the tack we took on all arguable issues.

Well, there was one other issue. Tim and Ted had a little fun with me. As I mentioned earlier, Tim acted as coordinator on the project, so he fielded a lot of the calls from Ted, and also got the copies of the artwork, which he then copied and sent on to me. Fairly early on, along with some other "character sketches", Ted sent a picture of Davy Crockett—complete with beard, buckskins, and coonskin cap. I just bit my tongue. Finally, months later, while Tim and I were discussing the artwork in depth, I blurted out that Ted was going to have to do a decent Crockett that was historically accurate and didn't look like Arthur Hunnicutt from THE LAST COMMAND. Tim cracked up and said he and Ted wondered how long it would take me to say something about that picture! I'd been had. Needless to say, Ted did other accurate pictures of Crockett, and the Hunnicutt version wound up in the "Alamo Movies" section—where they always meant it to.

ADP: Tim and Terry are both from Michigan, while Ted is from Oklahoma. Did the distance cause any problems as far as coordinating on the illustrations?

Tim: It would have been nicer if we could have sat down with Ted every few days to critique his progress, but I won't say that the distance caused us any serious problems. Ted is pretty much responsible for the content of the illustrations. There were a few times when we asked him to make changes, but most of the time he did his own research on what he portrayed in the various scenes. As I said above, we asked Ted to provide certain specific illustrations, but most of the ideas are entirely his own. Ted is pretty much a self-taught artist. His drawings of people have sort of a "folk art" look to them, but I think this gives them a special character. And it will say that I think that his illustrations of weapons and accouterments are second to none.

Terry: Other than the story cited above, no.

ADP: Who provided the captions for the illustrations?

Tim: Ted provided us with brief captions, and/or descriptions of what is included in the various scenes, but the detailed captions that appear in the published book were for the most part written by the author of that particular chapter or section.

Terry: We each did the captions for the illustrations that appeared in our sections.

ADP: From your biographies, it appears that you all have a great interest in the French and Indian War. As a native Pennsylvanian, that period of history has always held great interest for me. What are some other historical periods that you find especially interesting?

Tim: You're right, the French & Indian War is a major interest of mine. I always have been interested in nearly all periods of history, but my favorites are the F&I War and the Alamo. Other favorites are the War of 1812, the settlement of the Northwest Territory, and the Plains Indian Wars.

Ted: I have always been interested in the French and Indian War. In fact, I first met the Todish brothers fifteen years ago, through Rogers' Rangers and French and Indian War reenacting. I am also interested in many aspects of American history.

Terry: I'm kind of all over the map here.

I'm fascinated by late Roman Britain and King Arthur. I'm part Irish, so I'm somewhat into British Isles history, especially the Irish and Scots. I like the Old Northwest and War of 1812 period because it's local history here in the Midwest, and there are some great characters and stories. Ever since I was a little kid, I've loved the Old West, especially the Cavalry & Indians. And I love "historical mysteries"—the Masons, conspiracies, Jack the Ripper, that sort of thing.

ADP: Do your other historical interests provide insight or special knowledge that aid your understanding of the period of the Texas Revolution?

Tim: Definitely. A good knowledge of our Colonial period and the early days of our country helped me to better understand the thoughts and beliefs of the founders of the Republic of Texas. My overall knowledge of military history helped me to better understand the Mexican Army. One thing that I hope readers take special note of, is my argument that the thinking of the great military theorist Vauban probably influenced both sides at the Siege of the Alamo. (See pp. 41-42, 45, 48). Knowledge of Vauban helps to explain some of the things during the siege that otherwise might seem kind of strange to us in this day and age. For example, many people today are abhorred by the idea that any of the defenders might have even thought of giving up. However, under Vauban's philosophy, it would be perfectly normal, if not expected, for a besieged garrison to surrender once all hope was gone. It was also expected that the vanquished enemy would be treated humanely.

Terry: One thing that really helped me was my interest in the Gaels. Supposedly one of Travis' favorite books was "The Scottish Chiefs". And, as I mentioned in the book, there's a recruiting poster for the Texans that uses the phrase "Now's the day and now's the hour". That's from Robert Burns' "Scots Wha Hae," which is about the Bruce and William Wallace. Seeing that poster really struck me with how much the Texians saw themselves as the spiritual and literal sons of the kind of men we saw in "Braveheart."

Also, I'm a big fan of Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe novels. He's given incredibly vivid descriptions of the French attack in column—which is how Santa Anna's troops assaulted the Alamo. It helped me visualize just how the assault looked.

And, of course, my interest in the Masons led me to write the sidebar about the role of the Masons in Mexican politics.

ADP: Some of the more valuable features of The Alamo Sourcebook, at least in my opinion, are the fine detailed drawings of the weapons and accouterments used in the battle. Besides your own collection, what sources did you use?

Ted: I personally, over a three-year period, visited every gun museum, antique store, clothing museum, and anyplace anything that could have been germane to the weapons, costuming, artillery, construction procedures, and everything that we put on paper. The research was vast and lengthy. I'm certainly glad that we did it, but I don't know if any other subject would ever gain so much of my time and attention. We originally planned a 70-90 page sketchbook. Within a few months of our early production, we said that, if we were going to tell/draw/paint this story, we would do the story and then we would count the pages. And, to my way of thinking, the Todish brothers accompanied my artwork with vast amounts of text and, together, we have certainly created what I feel is the greatest reading and visual piece of Alamo material available to-date. Perhaps, as more information becomes available to us, and we certainly welcome any and all information, we would be most happy to revise future editions for all men everywhere.

I would like to say this about uniform and gun museums, those things we see the most of are those that saw the least use. They do not accurately represent what was actually worn and used by the cowboy riding the range in 1876, by the sodbuster plowing his fields in 1896, or by the men who died defending the adobe walls of the Alamo in 1836. The museums contain, usually, those items utilized by the wealthiest, and not by the common men and women of the time.

ADP: Did you uncover anything, while researching your book, which surprised you or seemed to go against popular concepts?

Tim: Since I had been a student of the Alamo for some time, I can't say that anything about the Alamo itself really surprised me, although writing about it made me reflect more deeply to bring things into perspective for the book. For example, we really had to think about how we wanted to handle Crockett's death. Also, when we began writing the book, I had just recently learned about the mystery of Edward Edwards. That really fascinated me at the time, and it still does today.

One thing that truly did surprise me does not have to do with historical facts, but with the generosity of the many, many people who helped us with the book. There were those who unselfishly gave us the results of their own work to use in the book, as well as those who took their time to review and critique the drafts of what we had written. Mere mention in our "Acknowledgments" does not fully reflect how much we really owe the success of the book to these people.

Terry: There are two things I can think of. I'd suspected even before we began this project.

It was very likely there was an attempted breakout from the area of the south wall after the north wall had fallen. While we didn't find any proof of this, the possibility became more likely the more we researched the battle in depth.

I was also interested to find that in the fall of 1835, while the colonists were seriously considering independence, it was largely through the work of the War Dog Sam Houston that Texas restated its commitment to the Constitution of 1824 and to supporting those in Mexico fighting against Santa Anna and for the Constitution.

ADP: If you were to start your book over again, is there anything you would do different, and—if so—what?

Tim: I don't mean to imply that we knew it all then, or that we know it all today, but I cannot think of anything that I would do drastically different. Before we started writing, we developed what we felt was a good plan, and we stuck to it. This included the basic layout and design of the book, the market niche that we would be seeking, and the price range where we wanted to book to fall. These are important considerations in any book project, but the time to think about them is before you begin to write, and not after.

Terry: I can't think of anything I'd do differently except incorporate the new research that's come up since publication.

ADP: The only error I was able to spot is that you confuse Erastus "Deaf" Smith and John W. "Colorado" Smith at times; for instance, in Chapter Seven, you have Colonel Travis sending Dr. John Sutherland & "Deaf" Smith on reconnaissance when it was actually John Smith who accompanied Dr. Sutherland. You later got it right in Chapter Nine, Part 3: Survivors of the Alamo. Would you like to comment on that?

Terry: The only explanation I can come up with is momentary insanity, it must have looked right and we didn't catch it in proofreading.

Tim: Even though every part of the book was read and re-read, then read again, a few glitches did slip by us. I have been told by authors far more competent than I that this is inevitable. This may well be true, but it is certainly not acceptable by my standards. I do not offer any excuses. By way of explanation, however, I will offer that when you are working so close to this much material, for so long a period of time, you sometimes just miss things, even though you know better. That is why having other knowledgeable people review your work is so important, and also why your own proofreading is absolutely essential. In the end, you, the author, are ultimately responsible. I will say that without the extremely valuable assistance of Melissa Roberts, our editor from Eakin Press, even more mistakes would have slipped by.

Ted: Although I'm sure there are some few small errors, here and there, the true lions' share of the artwork will stand the test of time, and that the drawings we finally chose to go to press with will be a benchmark that subsequent works will have to follow. There are different interpretations of the Alamo compound, based on different accounts, but my illustrations, based on the records and information available today, I feel is as close to being historically accurate as it is possible to get.

ADP: Some of your sketches of the Alamo compound show different interpretations of the same area, clearly marked as to being based on different accounts, movie renditions, etc. Does the illustration on the back cover capture your present interpretation, or have you revised that since the book was written?

Ted: Yes, the back cover contains my final interpretation and I feel that this is as accurate a depiction as possible.

ADP: Do you have any favorite illustrations?

Ted: My favorite illustration is that of the death of Crockett. Not what I consider to be my best, but my favorite because it expounds upon the controversy that we really don't know how David died. Was he bayoneted to death, bludgeoned to death, shot to death? We simply don't know. I placed him in very close proximity to Susannah Dickenson's eyewitness account of where she viewed his body. I also made sure that in the details of this painting, I dressed him in the clothing of contemporary accounts.

ADP: You said, "painting." Not being an artist, I thought they were pen and ink drawings.

Ted: The illustrations were watercolor paintings in sepia tones. They were done in black and white to give a photographic impression, as if a combat photographer may have been present. The only color illustration was the Alamo compound foldout. The fifth drawing was the final accepted version. The cover color work was an idea presented by Tim and Terry, that I did for them -- an idea that was originally discussed and drawn on a dinner napkin with a felt tip pen, one year before our first serious drawings began, in the early 1990s.

I think the hardest thing for me to draw in the entire book was to leave the circles off the top of the Mexican shakos (Walt Disney liked them, too). But our research showed that the circles had been gone for many years at the time the battle took place.

Although some people may have the impression, or think that the drawings were easy to do, because I had done many previous to this, the drawings represented in the book were the mere tip of an artwork iceberg. Everything that we finally printed had been drawn, critiqued, discussed, and redrawn.

ADP: How did you coordinate your illustrations over the many miles separating you from the Todish brothers?

Ted: We sent drawings back and forth through the mail dozens of times. Our telephone bills were astronomical and the letter writing between us, at times, was nearly daily — literally dozens and dozens, at times hundreds, of pieces of correspondence. Our telephone and mail costs, totaling hundreds of dollars in personal expense were incurred by the Todishes and myself to coordinate the artwork to the text, or the text to the artwork, depending on how you want to look at it.

Tim: Actually, large packages of illustrations also went out to our "consultants," (especially Kevin Young, Charles Lara, and Peter Stines), and along with the text, they also had a lot of welcome input on the look of the artwork.

ADP: The Alamo plats by Gary Zaboly and George Nelson both show a small tower at the southwest corner of the chapel. On page 57, you show a drawing of the chapel containing this, with a cannon in the tower. You say, "the scaffolding and artillery piece in the front of the chapel is a fixture in most Alamo movies, but it is doubtful that it really existed." It still makes an effective drawing. Tell me a little about it.

Terry: The platform may have existed -there's some evidence that it did. But it is highly unlikely it was a gun position. I think that's what was meant by the caption. But I'll defer to Tim and Ted if they have more information on this.

Ted: I feel about the cannon in the chapel tower much like John Ford, if that ain't the way it was, it sure should have been. I drew it, you Alamo buffs will understand what I say, in honor of Lawrence Harvey's foot. Historically, nobody's sure, but the one thing I do know, I stand firm in my belief that there is no one who can convince me it wasn't there.

ADP: You did a lot of illustrations of the New Orleans Grays in Alamo Sourcebook. ADP had a series a few months ago about the uniforms of the Grays. What are your thoughts on the uniforms, if any, worn by the Grays?

Ted: The New Orleans Grays were drawn in uniforms for the Alamo book. They were put in uniforms to show what they may well have looked like. To my way of thinking, only a fool would insist that the Grays arrived in Bexar all looking 100% "National Guard." I might also add that it would be a bigger fool who would insist that no items of uniformity would have existed with an established militia company or with an established, well known group of fighting men such as the Grays. The condition of their uniforms (repair, appearance and uniformity) would truly be left to some conjecture. Nothing frosts me more, or chills my bones more, than to read any article written by anyone that says, "this is the way it was." As no one, to include myself and all other historical artists that I know, can paint any historical scene without employing hypotheses and assumptions, all based on flat-out good sense.

Final note, by Tim: It is very likely that we will be offering all of the original artwork for sale as a complete set in the not too distant future. We must first determine a fair asking price, or we may decide to go to some kind of an auction. If anyone is seriously interested, they can contact me by letter.

Also, anyone who wants to can get a personally autographed copy of Alamo Sourcebook 1836 directly from me. I have an adequate supply, and they are all also signed by Terry. The cost is still $21.95, plus 6% sales tax for Michigan residents. Shipping (Priority Mail) is $3.50 for the first book, and $1.00 each for additional copies to the same address. My address is 4925 Oakway Ct. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49525-6836.

The artwork consists of approximately 150 scenes on 81/2 x 11 or 10 x 12 inch paper. Most of the illustrations are what Ted calls "sepia half-tones." They are not "full color," but are shaded, mainly with browns, grays, and blues in a manner to make them reproduce better in the book. This technique gives the originals a very interesting look.

ADP: Thanks for your time and cooperation. It has been a lot of fun for me; I hope it has for you, also.

Interview conducted 11/99 by Robert L. Durham, Contributing Editor to Alamo de Parras

![]()