The Account

of

Concerning the Fall of the Alamo

One of the Besiegers Tells the Story

of the Siege and Final Assault.

Frightful Scenes of Carnage-Death of

Travis and The "Man In The Fox skin Cap."

How the Bodies Were Collected and Burned-Horrible

Scenes Depicted by an Eye-Witness.

[Felix Nuñez is an aged Mexican who has lived

in this and adjoining counties since the year 1837, and has long been

noted among his neighbors for his wonderfully retentive memory and power

of description. He bears an unexceptional [?]reputation for truth and

veracity, and THE EXPRESS has

the assurance of many well known and reliable citizens of this county

that in what he says he conscientiously endeavors to tell the truth, and

that if there are any inaccuracies in his statement they must be attributed

to incorrect information received at the time of which he writes. After

leaving the Mexican army Señor Nuñez reentered this country

on a passport purchased from a Mexican named Bacca, and issued to him

by General Sam Houston. Fearing punishment for his part in the war against

the Texans, he lived for several years under the name of Bacca. He say

she kept the coat of Travis and the papers contained therein secreted

about his premises until about eighteen years ago, when he found them

so worm-eaten and mouldy that he destroyed the remnants, having all the

time feared making his valuable possessions known, but desiring to retain

them as mementoes of one of the most tragic battles known to the history

of the world. The coat was "home made" of Texas jeans. Nuñez has

always been reticent about his part in the war of Texas Independence,

but a friend and neighbor for twenty-five years, Professor Geo. W. Noel,

to whom THE EXPRESS is indebted

for the interesting article to follow, has during that time taken notes

of statements made by Nuñez during his periods of confidence, and

having secured much information in that way, finally prevailed on the

old gentleman to make a corrected statement concerning the thrilling event,

and which the professor has translated for THE EXPRESS.12

Nuñez now lives near Amphion, in Atascosa county.] 13

My name is Felix Nuñez, and I was born in 1804,

and am consequently nearly 85 years old. I was forcibly conscripted in

1835 in the state of Guadalajara, Mexico, and was assigned to duty in

that division of the Mexican army which was always under the immediate

command of President Santa Anna, and, as I was then 32 years of age, you

will see that I had a good opportunity for knowing and observing every

event that transpired within my sphere from the time of my enlistment

until the unfortunate encounter at San Jacinto, April 21 , 1836.

General Santa Anna with an army of 7,000 men started from Guerrero,

Mexico, about the middle of February, 1836, and though marching on double

quick time we did not arrive at San Antonio until near the end of that

month.14

There was some delay at El Paso de la Pinta, on the Medina, occasioned

by the death of a colonel of one of the regiments and a favorite of

General Santa Anna, who ordered this officer to be buried with the honors

of war.15 Santa Anna, not

wishing to take part in the obsequies of his deceased friend, moved

on with his staff and the division of troops under his immediate command,

and halted on the Alazan, a little west of the city. Shortly after his

arrival at the Alazan he learned that there was a baile (a dance) going

to take place in the Domingo Bustillo house, which is just north of

the Southern hotel. Obtaining this information, Santa Anna doffed his

regimentals and disguised himself as a muleteer and went to the dance.

There he learned the exact force and number of the troops that were

in the city and all other necessary information, as well, also, the

feeling of the citizens in regard to the invasion. The president, being

an elegant talker and avery brilliant conversationalist, directed his

conversation to the Americans and Mexican citizens who were in sympathy

with the American cause. One of the incidents I recollect distinctly.

It was a very heated controversy that took place between Gen. Santa

Anna and Señor Vergara, the father-in-law of Capt. Jno. W. Smith

16 (of whom I shall speak

again), in which this gentleman gave Santa Anna an unmerciful abusing

and hooted at the ideal of the Mexicans ever subjugating the Americans.

Just after the fall of the Alamo Gen. Santa Anna sent his orderly to

Señor Vergara and commanded him to appear before him. Upon being

asked if here collected the conversation with the muleteer he was almost

scared out of his wits. He was reprimanded by Santa Anna, who told him

to go his way and sin no more. Here the president completely disguised,

was talking and chatting in company with some of the Americans who had

come over from the Alamo and participated in the festivities of the

dance, not even dreaming that they were in such close proximity to the

one who would shortly spread before them the last and fatal feast of

death.17

After the army invested San Antonio and the Americans had retreated

to the Alamo, Santa Anna ordered the Americans to surrender.

The summons was answered by those of the Alamo by the discharge of

a cannon, whereupon Santa Anna caused a blood-red flag to be hoisted

from the Cathedral of San Fernando on the west side of the Main plaza,

which at that time was in plain view of the Alamo.18

Simultaneously [sic] all the bugles sounded a charge all along

the lines of both cavalry and infantry, but this charge was repulsed

by the Americans with heavy loss to us.19

Whereupon the President ordered "sapas" (subterranean houses) to be

dug on the north, south and east of the Alamo, which were strongly garrisoned

with troops, for the double purpose of preventing re-inforcements from

entering the Alamo and to cut the Americans off from water.20

This completed the cordon of troops which was drawn around the doomed

Alamo. And right here let me state that no ingress or egress could have

been accomplished from the time our army regularly besieged the Alamo,

and there was none,with the single exception of Don Juan Seguin and

his company, who were permitted to leave. They were let go from the

fact that they were Mexicans and we did not wish to harm them.2l

There was no Capt. John W. Smith and company, nor no one else ever

cut their way through our lines and entered the Alamo, because they

would have been cut to pieces in the attempt, for the main object of

Santa Anna was to keep the garrison from receiving reinforcements.22

And, moreover, there is but one Captain Jonh [sic] W. Smith mentioned

about San Antonio and he was mayor of the city at the time of the desperate

fight with the Comanche chiefs on the east side of the Main plaza.23

If he had been in the Alamo he would have been killed, and therefore

could not have been mayor of San Antonio afterwards.24

The second and third day of the siege resulted with very little variance

from the first, to-wit: With heavy losses to our army. This so exasperated

Santa Anna that he said, to use his own language, that he was losing

the flower of his army, and to see the Alamo still hold out he became

terribly enraged, and it was at this time that he made the fatal promise,

which he so scrupulously carried out, that he would burn the last one

of them when taken whether dead or alive. He immediately called a council

of all his officers and proposed another attack on the Alamo in the

evening of the third day's siege with his entire force. His cry was:

"On to the Alamo."This was met with the cry by the officers and men

that: "On to the Alamo was on to death."

A large majority of the officers were in favor of waiting until they

could get more heavy cannon and, perhaps by that time the garrison would

be starved out and surrender and further bloodshed be avoided.25

But Santa Anna, with his usual impetuosity, swore that he

would take the fort the next day or die in the attempt. So on Wednesday,

the 6th day of March, 1836, and the fourth day of the siege, was the

time fixed for the final assault.26

Each and everything pertaining to the final assault underwent the personal

supervision of General Santa Anna, to the end that it would be successful.27

Three of his most experienced officers were selected to assist him in

commanding the assaulting parties. General Vicente Felisola [sic], his

second in command,with a thousand picked men took charge of the assault

on the east of the Alamo.28

General Castrillor [sic],with a like number, was placed on the south

side.29 General Ramirez Sesma

30 was to have taken command

on the west side next to the river, but seeing that President Santa

Anna was determined to make the final assault the next day feigned sickness,

the evening before, and was put under arrest and started back to the

capital. This part of the command then devolved on Gen. Woll,31

so there was no General Sesma in command of any portion of the army

at the fall of the Alamo, nor afterwards.32

The troops on the north and northwest, 1,500 in number, were commanded

by General Santa Anna in person.33

This made 4,500 men who participated in the engagement.34

In addition to this, there was a fatigue party well supplied with ladders,crowbars

and axes for the purpose of making breaches in the walls, or at any

other vulnerable point.35

The infantry were formed nearest the Alamo, as we made the least noise.

The cavalry was formed around on the outside of the infantry, with special

orders from all of the commanders to cut down every one who dared to

turn back.

Everything being in readiness just at dawn of the day on the 6th

of March, and the fourth day of the siege, all the bugles sounded a charge from

all points.36 At this time our cannon

had battered down nearly all the walls that enclosed the church,consequently

all the Americans had taken refuge inside the church, and the front door of

the main entrance fronting to the west was open.37

Just out side of this door Col. Travis was working his cannon. The division

of our army on the west was the first to open fire. They fired from the bed

of the river near where the opera house now stands. The first fire from the

cannon of the Alamo passed over our heads and did no harm; but as the troops

were advancing the second one opened a lane in our lines at least fifty feet

broad.38 Our troops rallied and

returned a terrible fire of cannon and small arms. After this the cannonading

from the Alamo was heard no more. It is evident that this discharge killed Travis,

for then the front door was closed and no more Americans were seen outside.

By this time the court yard, the doors,the windows, roof and all around the

doomed Alamo became one reeking mass of armed humanity. Each one of us vied

with the other for the honor of entering the Alamo first. Just at sunrise a

lone marksman appeared on top of the church and fired. A colonel was struck

in the neck by this shot and died at sundown. This the officers took as an evidence

that the Americans had opened a hole in the roof themselves.39

This proved to be true, for almost in the next moment another American appeared

on top of the roof with a little boy in his arms, apparently about three years

old, and attempted to jump off, but they were immediately riddled with bullets

and both fell lifeless to the ground.40

With this the troops pressed on, receiving a deadly fire from the top of the

roof, when it was discovered that the Americans had constructed a curious kind

of ladder, or gangway, of long poles tied together with ropes and filled up

on top with sticks and dirt. This reached from the floor on the inside of the

church to over the top edge of the wall, to the ground on the outside.41

As soon as this discovery was made Santa Anna ordered his entire division to

charge and make for the gangway and hole in the roof. But most of the soldiers

who showed themselves at this place got not into the Alamo, but into another

world, for nearly every one of them was killed. We then found out that all the

Americans were alive inside of the church. During the entire siege up to this

time we had not killed even a single one, except Colonel Travis and the man

and boy referred to, for afterwards there were no new graves nor dead bodies

in an advanced state of decomposition discovered.

By this time the front door was battered down and the conflict had

become general. The entire army came pouring in from all sides, and

never in all my life did I witness or hear of such a hand to hand conflict.

The Americans fought with the bravery and desperation of tigers, although

seeing that they were contending against the fearful odds of at least

two hundred to one, not one single one of them tried to escape or asked

for quarter, the last one fighting with as much bravery and animation

as at first.42 None of them

hid in rooms nor asked for quarter, for they knew none would be given.43

On the contrary,they all died like heroes, selling their lives as dear

as possible. There was but one man killed in a room [?], and this was

a sick man in the big room on the left of the main entrance. He was

bayoneted in his bed. He died apparently without shedding a drop of

blood.44 The last moments

of the conflict became terrible in the extreme. The soldiers in the

moments of victory became entirely uncontrollable, and, owing to the

darkness of the building and the smoke of the battle, fell to killing

one another, not being able to distinguish friend from foe. Genera[l]

Filisola was the first one to make this discovery. He reported it to

General Santa Anna, who at once mounted the walls. Although the voice

of our idolized commander could scarcely be heard above the din and

roar of battle, his presence together with the majestic waving of his

sword sufficed to stop the bloody carnage, but not until all buglers

entered the church and sounded a retreat, did the horrible butchery

entirely cease.45 To recount

the individual deeds of valor, of the brave men who were slain in the

Alamo, would fill a volume as large as the History of Texas; nevertheless

there was one who perished in that memorable conflict who is entitled

to a passing notice. The one to whom I refer was killed just inside

of the front door. The peculiarity of his dress, and his undaunted courage

attracted the attention of several of us, both officers and men.

He was a tall American of rather dark complexion and had on a long

cuera (buck skin coat) and a round cap without any bill, and made of

fox skin, with the long tail hanging down his back.This man apparently

had a charmed life.Of the many soldiers who took deliberate aim at him

and fired, not one ever hit him.On the contrary he never missed a shot.

|

click picture to enlarge

|

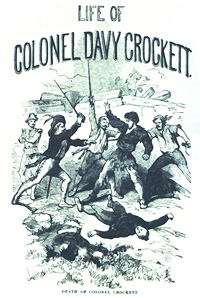

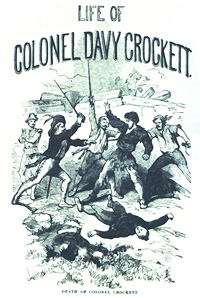

In contrast to

the traditional image of David Crockett going down fighting, this woodcut

from an 1869 edition of Crockett's autobiography depicts stereotypical

Mexicans falling on an unarmed Crockett with their swords while a haughty

Santa Anna observes the summary execution. This illustration follows closely

the details of Mexican officer Enrique de la Peña's account of

the battle, which claims that Crockett was captured during the battle

and put to death immediately afterward. His body was then burned along

with those of all the other Alamo defenders. The two versions of Crockett's

death-fighting to the end, and being executed. After the battle-were both

popularized during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Only

after Walt Disney's wildly popular 1955 television movie about Crockett

had him die fighting did the notion that Crockett might have been captured

and executed arouse controversy.

|

|

Courtesy Barker

Texas History Center,

University of Texas at Austin.

|

|

He killed at least eight of our men, besides wounding several others.

This fact being observed by a lieutenant who had come in over the wall

he sprung at him and dealt him a deadly blow with his sword, just above

the right eye, which felled him to the ground and in an instant he was

pierced by not less than twenty bayonets.46

This lieutenant said that if all Americans had have killed as many of

our men as this one had, our army would have been annihilated before

the Alamo could have been taken. He was about the last man that was

killed.

After all the firing had ceased and the smoke cleared away, we found

in the large room to the right of the main entrance three persons, two

Mexican women named Juana De Melto and La Quintanilla and a negro boy,

about fifteen or sixteen years old who told us that he was the servant

of Colonel Travis.47 If there

had been any other persons in the Alamo they would have been killed,

for General Santa Anna had ordered us not to spare neither age nor sex,

especially of those who were Americans or American descent.48

On the floor of the main building there was a sight which beggared

all description. The earthen floor was nearly shoe-mouth deep in blood

and weltering there in laid 500 dead bodies, many of them still clinched

together with one hand, while the other held fast a sword, a pistol

or a gun, which betokened the kind of conflict which had just ended.

General Santa Anna immediately ordered every one of the Americans to

be dragged out and burnt. The infantry was ordered to tie on the ropes,and

the cavalry to do the dragging. When the infantry commenced to tie the

ropes to the dead bodies they could not tell our soldiers from the Americans,

from the fact that their uniforms and clothes were so stained with blood

and smoke and their faces so besmeared with gore and blackened that

one could not distinguish the one from the other.49

This fact was reported to Santa Anna and he appeared at the front and

gave instructions to have every face wiped off and for the men to be

particular not to mistake any of our men for Americans and burn them,

but to give them decent sepulture. He stood for a moment gazing on the

horrid and ghastly spectacle before him, but soon retired and was seen

no more.

When the Americans were all dragged out and counted there were 180

including officers and men.50

Upon the other hand this four day's siege and capture of the Alamo cost

the Mexican nation at least a thousand men, including killed and wounded,

a large majority of this number being killed.51

Our officers, after the battle was over, were of the opinion that if

the Americans had not made holes in the roof themselves, the Alamo could

not have been taken by assault. It would either have had to have been

starved out or demolished by heavy artillery.

After we had finished our task of burning the Americans a few of us

went back to the Alamo to see if we could pick up any valuables, but

we could not find anything scarcely, except their arms and a few cooking

utensils and some clothing. I found Colonel Travis' coat, which was

hanging on a peg driven to the wall just behind the cannon and from

where his dead body had just been dragged away. In the pockets I found

some papers that resembled paper money or bonds of some kind.52

His cannon was standing just as he had left it with its mouth pointing

west and not towards the Alamo plaza. We did not use Colonel Travis'

cannon, nor even our own, because cannons were almost useless on the

day that we made the final assault.53

The next movement inaugurated by Santa Anna was to set out for the

interior of Texas, and, as I have stated before, that I belonged to

the division under his immediate command, I accompanied the invading

army and was taken prisoner by the Americans at the battle of San Jacinto.

After San Jacinto I resolved never to take up arms against my fellowman[sic]

again and promised myself never to return to the army that had been

triumphant in so many hard fought battles-an army that was commanded

by(as he always called himself) "the Napoleon of the West," but had

just been so completely defeated, nay, annihilated, by a handful of

poor undisciplined half-armed Americans.

In conclusion, permit me to state that I have no object in giving this

description of the fall of the Alamo only as a response to the solicitations

of my friend and benefactor, Mr. G. W. Noel, who has been talking to

me occasionally for the last twenty-five years and taking notes for

the purpose of writing a true account of the siege and capture as detailed

by one of the assaulting party, that those heroic deeds of valor for

which his countrymen are so justly famous may be handed down to—posterity

free from those errors into which some of the historians of Texas have

so innocently and unknowingly fallen. And to add solemnity to this occasion

and veneration for the "martyred heroes of the Alamo" he has seen fit

to make this account public, upon the very spot of ground that was drenched

with their blood and at the very place where the air was filled with

the fumes of their roasting flesh.

—Felix Nuñez

![]()

![]()