SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS For Biographies, Search Handbook of Texas Online MEMOIRS

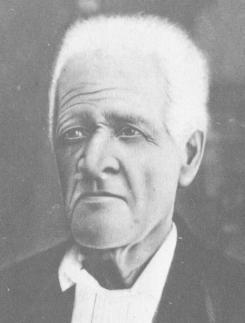

The manuscript of Antonio Menchaca's Memoirs is in possession of Pearson Newcomb, of San Antonio, Texas. According to Mr. Newcomb, Antonio Menchaca dictated his memoirs to Charles M. Barnes, in whose handwriting they are preserved.[Portrait from Lozano, Viva Tejas, 1936; original from HA McArdle Notebooks, Texas State Library and Archive Commission] Marcos Menchaca was in military service at the presidios at San Xavier, at San Marcos, and at San Saba. In 1762 he received a grant of land in San Antonio, on the San Pedro, bounded on the east by a Camino Real, and by his own lands. He married Josefa Cadena and they had two sons, Juan Mariano and Joseph Manuel. Juan Mariano Menchaca married Maria Luz Guerra and they were the parents of Joseph Antonio Menchaca, Texas patriot, and author of the memoirs, born in January, 1800. He married Teresa Ramon, daughter of Martin Ramon (and his wife Ana Aguilar), descendants of the military leaders of the expeditions into Texas in the early 1700's. Antonio Menchaca and his wife Teresa Ramon, had a daughter Joaquina who married John Glanton, a daughter Maria Antonia, who married P. E. Neuendorff, and a daughter Antonia Manuela, who married Jean Batiste Ducuron La Coste, of Gascony, France (parents of Zuleme, who married Ferdinand Herff, Maria, Sofia, Lucien, Nita and Amelie). The Yanaguana Society is grateful to Mr. Newcomb for his kindness in permitting the publication of these memoirs, with the Introduction by James P. Newcomb (his father) published in the Passing Show, San Antonio, Texas, in weekly installments, from June 22 to July 27, 1907, John B. Carrington, Ed. and J. E. Jones, Adv. Mgr. FREDERICK C. CHABOT. INTRODUCTION I knew Captain Antonio Menchaca personally, and enjoyed his friendship and confidence. He was a distinguished man in his day and generation. In personal appearance he was physically a large man, not overly tall, but massive; his complexion fair, his eyes blue, his countenance strong and dignified; he bore the marks of a long line of Castilian ancestors. He took an active part in the stirring events of the early period of the history of San Antonio. His sympathies carried him into the ranks of the Americans; he was an ardent republican---he became a warm friend of Bowie and Gen. Sam Houston and, having a bright mind, remembered well the principal characters of the Texas revolution. It is of an early day I speak, when I recall Captain Menchaca as the umpire at the Sunday cock fight. Amusements and entertainments in those days, half a century or more ago, were limited to the Sunday cock fight-the fandango-the Saint's days. It was at a period when the old Mexican shoemaker, Gallardo, whose shop faced the east side of the Main Plaza, about where Brady's saloon is today (1907), tied his fighting cocks out on the sidewalk and when on Sunday, services in the old San Fernando church being over, the cock fights came off in the shadow of the tower of the belfry. Those were happy, serene days, when the people were not possessed with a mania for money getting-when the real estate business was unknown; when the clean, bright river was a common bathing resort and the summer sun slipped behind the ancient walls to give a shade to the simple sports of the contented population. It required a man of stern character and unbending dignity to decide the fine points of these tournaments. In later years, when the titles to almost every foot of ground in the old city and county of Bexar were litigated in the courts, Captain Menchaca became a standing witness to prove up the genealogy of the old families; his memory was so bright that every incident in the history of the old Spanish settlers was perfectly at his command. To the litigants whose interests his testimony controverted and the bar that decided the story, he became something of a terror, but no one ever doubted the truth of his evidence. When any citizen of San Antonio visited Austin, the state capital, while General Houston was governor, the first inquiry of old Sam was, "How is my old friend, Captain Menchaca, getting along?" Captain Menchaca's descendants are among our best citizenship; the Lacoste family are splendid in the qualities of intelligence, gentility and worthiness. Some years ago, over a quarter of a century-though, I think, after the civil war---I met Captain Menchaca and our conversation turned upon the discussion of events of early Texas history. When he related in a clear and concise manner many striking circumstances, I suggested that I would like the privilege of transcribing his narrative. Thereupon he volunteered to furnish me the manuscript which he would have properly prepared. In accordance with his promise he handed me a plainly written history of events from the date of his birth to the battle of San Jacinto. I have never used the story and have had little opportunity to examine it critically. It is evident the amanuensis who took down the old Captain's story put it down without coloring, and one regrets that he did not enlarge more fully upon details that are so full of historic and romantic interest. Neither have I compared the story with the current published history of Texas, particularly that of the important battle of San Jacinto, upon which turned the fate and destiny of the great American republic and brought about the expansion that reached to the waters of the Pacific and the uncovering of the gold fields of California. I have taken no liberties with the manuscript and give it to you as it is, in all its barrenness of invention and lack of coloring that would be justified for a period fraught with terrible tragedies and wild romance. JAMES P. NEWCOMB. MEMOIRS I was born in 1800. Was baptized in the church of San Fernando de Austria [San Fernando de Bexar] on the 12 Jan. same year; was raised in San F. de A. up to the year 1807 from which time up he can remember when came the express order from the King of Spain to the Lt. Col. Antonio Cordero to select 250 men from the King's service to go and establish the Spanish line on the Sabine River. He did so and went to "reconocer." Having returned from the Sabine River he left at Nacogdoches 100 men for the safe guard of the Spanish law, that it be respected and obeyed. When he had concluded his Military business at Nacogdoches he returned to San Fernando de Austria. Having arrived here he took upon himself the task of improving the City. He straightened streets; Main Street, so called now, was at that time a very crooked one, running straight from the Plaza up to where the street from Lewis Mill intersects it, thence to the Mill. He cut the street straight, built bridge and Powder House. Also straightened Flores Street. While Governor he was very good and kind doing many things for the welfare of the people. In 1811 Manuel Salcedo, Lt. Col. of the Royal Spanish Armies succeeded Cordero; Salcedo being Gov. secret letters were received here by parties who desired to throw off the Spanish yoke, from parties in Mexico, Hidalgo, Ximenes, and El Pachon inviting them here to join them in their enterprise. Many of these answered them that they could rely upon help from here; that there were a great many here who would willingly enter into the plot. These parties here while considering the measures they were to adopt to secure their ends, were suspected and from 15 to 20 of the leaders were arrested; some were shot, others remained here in prison; others were sent to Chihuahua prison. Among those who were sent to Chihuahua was Captain Jose Menchaca who remained imprisoned till his death in 1820. The main leader, Juan Bautista Casas was here in prison for a while, then taken to Monclova where he was shot; his head severed from his body, placed in a box, sent here and put in the middle of Military Plaza on a pole. At the same time that Casas was killed, Ayendes, Hidalgo, Ximenes and El Grachon, who were on their way to San Antonio with $3,000,000 Dollars, were apprehended, killed and all the property destroyed. On the 11th of March, 1811 an order was received from the Viceroy, Felix Maria Calleja, that San Fernando de Austria [de Bexar] and San Antonio de Balero should be incorporated under the name of San Antonio Bexar. In 1812, Juan Zambrano, a citizen of this place, being a man who owned a great many sheep, having 77,000 sheep; determined to put four droves of mules loaded with wool on the road to Nacogdoches. He went to Nacogdoches, arrived there and there some of his friends informed him of his projected death. Bernardo Gutierres and Miguel Menchaca had 300 men, he left Nacogdoches through the instructions of some of his friends, having lost all his wool and returned to S. A. arriving here towards latter part of August, and advised Gov. Salcedo of what was going on at Nacogdoches; who immediately sent couriers to the City of Mexico and Chihuahua notifying what was expected. By the month of November about 4000 troops had arrived here from different parts of Mexico. The American troops, (Magee) advancing towards Goliad (where they arrived on the 26th of November). The Mexican troops started from here to Goliad where they took possession of the Mission del Rosario and the Mission del Espiritu Santo, to consider their action. There they skirmished frequently with the Americans, but were always defeated; putting pickets out every night. They so remained during all the months of December, January and February (1813). On the 11th February, 1813, Captain Cordero, a Comanche Chief arrived at S. A. with 1500 Comanches and presented himself to Jose Flores de Abrego, who was in command here in the absence of the Governor; asking him for a "regalo". Jose Flores de Abrego told him that he could give him nothing that the Gov. was at Goliad in the war. Cordero then said that if he had nothing to give him that he wanted to speak with the Gov. and started for Goliad; arrived there with all his followers, presented himself to Salcedo, insinuating to him that he wanted "Regalo". Salcedo told him that he had no regalo, but that he could furnish him with powder and lead for him to assist him in fighting the Americans; but the Indian Chief answered him that he did not want to fight the Americans, that they were too brave and would kill too many of them, and that if he (Salcedo) did not give him a regalo that he (Cordero) would come and destroy all the ranches and take off all the horses. The Indians remained at camp three days, but Salcedo as soon as he found out their intentions sent an express to Flores directing him to have all the horses in the country brought into San Antonio and the town fortified, so that when the Indians returned they found all the ranches alone and the horses within San Antonio. The horses, about 7000 head were kept here, being herded by sixty men, for fifteen days, at which time about 2000 Indians came and took them all away. During all this time the Mexicans and Americans were fighting at Goliad, and continued through part of March on the 10th of which month the Mexicans finding they could not whip the Americans, started for San Antonio. The Americans gave them time to arrive at S. A. when they advanced and encamped on the Rosillo. The Mexicans went from S. A. and a fierce battle ensued in which the Americans were victorious, killing about 200 Spanish soldiers and a great many wounded. The Mexicans retreated in a bad condition; the Americans remained on the field. Three days after the Americans moved up and encamped at Concepcion Mission, being Thursday on Friday, Bernardo Gutierres and Miguel Menchaca, sent a herald to Manuel Salcedo stating that by next day at 10 o'clock, they wanted the S. A. plaza evacuated. The answer was sent through J. M. Veramendi, that at any time they chose to come in, no resistance would be offered. At the appointed hour on Saturday the Americans entered the City. At 3 o'clock of the same day the Americans imprisoned Miguel Delgado, Santiago Menchaca, Francisco Riojas, and twenty-one others of the American side, and Manuel Salcedo, Simon de Herrera, Geronimo Herrera, Francisco Povela, Miguel de Arcos, and old Capt. Graviel de Arcos, son of Capt. de Arcos, Miguel de Arcos, Jr., Miguel Pando, Juan Francisco Caso, and four others, of the Mexican side were all taken to the Salado, and arrived at the Rosillo the same evening and that same evening were beheaded; and by 8 o'clock next (Sunday) morning the twenty-five Americans were in the City and said that they had started the Mexicans to ship them to N. O. though they were infamously butchered as before stated. Then Bernardo Gutierres determined to establish good order in the City of San Antonio. He called a council, the president of which was Dr. Francisco Arocha, Thomas Arocha, Ignacio Arocha, Clemente Delgado, Manuel Delgado, Miguel Delgado and Antonio Delgado, all gentlemen of the City of San Antonio, descendants of the first families who emigrated from the Canary Islands in 1730; all adherents of the American Govt. In the same year (1813) on the 11th of June at night appeared here 1500 Mexican soldiers under the command of Ygnacio Elizondo, a Spanish Col.; Ygnacio Perez, Lt. Col. On the morning of the 12th June they were within 1 1/2 miles from City on the Alazan Hill. The Americans seeing that they were there, took one of the old Spanish guns that was here, a 12-pounder, placed it upon the old powder house which was built on the west side of San Pedro, and saluted the Mexicans with five shots from the gun. Gutierrez let them rest four days, while he rested his troops. On the fifth day at 8 o'clock A. M. he took his troop out and attacked the Mexicans with such force and effect as to entirely route them in about a half hour's fighting; killing forty or fifty, taking fifty or sixty prisoners, and the balance put to flight. Gutierrez brought prisoners into City and treated them very well. June passed, July came, on the 15th of which M. the American spies who had reconnoitered about Laredo returned and gave the Intelligence to Gutierrez, that Arredondo was raising a great many troops for the purpose of attacking San Antonio. On the same day that this news reached here Gen. Toledo from N. O. arrived here and relieved Gen. Gutierrez from the command of the troops. This latter upon being relieved left here for Natchitoches. The American spies were incessantly on the look-out, but [that] they should not be surprised watching Arredondo's movements, until he got to this side the Atascosa, when the spies came and told Toledo that the Mexican Army was on this side of the Atascoso and advancing. Then Toledo prepared to meet them started from here in the direction in which Arredondo was coming, slept at Laguna de la Espada the first, on the second he crossed the Medina River and on a hill, (a short distance the other side) he thought a convenient place to take the enemy at a disadvantage. Arredondo also coming to a place he considered advantageous to his purpose, stopped at the water holes called "Charcos de las Gallinas" on the hill this side of the Atascoso creek and about five miles from the Medina River. On the day following Arredondo's occupation of the said water holes, he sent a detachment of men, of about 400 strong, cavalry with two light pieces of artillery, to try and engage the Americans. (The detachment was under the command of Ygnacio Elizondo and Ygnacio Perez). They came up to the American troops and trying to engage them upon seeing which Miguel Menchaca, the second in command on the American side came up to Toledo and asked him what his intentions were. Toledo remarked to him that that maneuvering was only intended as a decoy and to ascertain the strength of his troops, that he (Menchaca) might take some of his men and engage with them but under no consideration to follow them far if they retreated; that Arredondo merely wished to get him out of his position in order to take him at a disadvantage. Menchaca went to attack them and did not return. He followed the detachment of Mexicans, killing all he could until he got up to the Main body. He took two guns from the cavalry, but was attacked by the artillery and he retreated for about 1/2 mile from where he sent word to Toledo to advance with his troops, for he (Menchaca) would not turn back. Toledo then sent word to him that it would be worse than madness for him to attempt to move forward and leave his position, for he would be sure to be defeated if he did. Upon receiving this word, Menchaca, infuriated, himself came over to where Toledo, with the balance of the force was and told the troops that the fight bad commenced; that under no consideration would he, having already commenced the fight, quit until he and the men under him had either died or conquered; that if they were men, to act as men and follow him, whereupon all the forces became encouraged and moved in a body to follow Menchaca. Toledo though unwillingly followed. They started to meet Arredondo, and having no water, also having to pull the guns along by hand, by the time they came to where Arredondo was and were placed in battle array, the troops were nearly dead from thirst. The battle began with great fury. As soon as it commenced, Menchaca, who commanded one wing of the Cavalry and Antonio Delgado, the left wing, pushed their men up with such vigor as to compel the cavalry which opposed them to retreat to the centre of the main body of Arredondo's Infantry. The Americans were so thirsty that they even drank the water in which the rods for loading the cannon were soaked in. The battle had almost been declared in favor of the Americans, when by an accident Col. Menchaca was struck by a ball on the neck. He fell, and there being no one to cheer the troops on, it became discouraged, then frightened; disorder commenced. The Mexicans, under Arredondo seeing this, took courage and charged with fury, got into the Americans and killed a great many of them. Though Menchaca was brought with them, died on the way and was buried on the Seguin road at the place called Menchaca Creek, or "Canada de Menchaca". Arredondo having come off victorious, came as far as the Laredo road crossing of the Medina, encamped to cure his wounded soldiers, have their clothes washed and at the same time to dispose of the prisoners he had taken, which he did by shooting them. The number he killed were about 250 (7 prisoners). After he had accomplished all this, he then came to San Antonio. It was about 10 o'clock, A. M. of the 15th of August, that he arrived here. The Catholic church was filled with poor men praying that their lives should be spared them. All were taken out, some placed in the old Spanish Guard house, and others crowded into the house of Francisco Arocha. Of those placed in this latter place, being so crowded, eight men suffocated to death by next morning. On the following day they were all taken out in line to ascertain which of them deserved to be put to death, and which to be put to hard labor. Arredondo ordered Ygnacio Perez, a native of San Antonio, to name two persons, of the natives that they might call out all such persons as were deserving of death, and to name also, all such as should be put to hard labor. Ynacio Perez nominated Luiz Galan and Manuel Salinas, who, though natives of S. A. answered that they knew no one. Upon hearing this, Arredondo selected forty which should be put to death, and the balance, 160, were handcuffed in pairs and sent to work upon the streets. Of the forty who were selected to die, every third day they would shoot three, opposite the Plaza House, until the entire number were disposed of. The wives of these unfortunates were placed inside the "Quinta" to make "tortillas" for the soldiers. They had to make 35000 tortillas daily. Six days after Arredondo's entry into the City, he ordered Ygnacio Elizondo and Ygnacio Perez, with 250 men to follow all the people who had started for Nacogdoches. They started and after they went away, Arredondo was very anxious to punish all those who had taken any part whatever in the Revolution; the result was that whosoever chose to have any one punished would merely complain to the officers and the chastisement would be secured by whipping them on the public square; something they very seldom excused; though there is an instance, where a party, Mariano Menchaca was accused of some trifling thing. The soldiers at dead of night went over to his house, took him and his wife out of their bed took the wife to the Quinta, and him they were going to whip, when, his son Antonio was then about fourteen years old and had become a favorite of one of the principal officers, Cristobal Dominguez; seeing that they were going to whip, ran into this officer's bedroom, where the officer was in bed, and going up to him told him that his father was about to be whipped and begged him to intercede for him. The officer, at first, told him to go away, but the boy would not be put off. He begged him for all that was dear to save his father. The officer finally relented and stepping out, he spoke to the men who had charge of the boy's father, made them turn him loose. The boy then asked him to please have his mother liberated; he gave him an order for her release, which he took to officer in command of the "Quinta" and got her released too. Elizondo and Perez overtook the fugitives on the Trinity River, which had swollen from heavy rains that had fallen. All the men of note had already crossed the river; only the women and inferior men remained on this side. The Spaniards had along with them a priest named Esteban Camacho. When the Spaniards arrived there the men presented themselves to the Commanders. The commanders asked them why they had rebelled that they would hurt nobody; as they would see. That they would be charitably treated, and that their only object in following them was to bring them back to their homes. The commanders asked if there was any man present who would cross the river and tell those on the other side; that if they came over to this side, a full pardon would be granted them. One of the men, of those who had not crossed over, agreed to go over and take the letter; in which was guaranteed to them, in the most sacred terms, a full and complete pardon if they would but give themselves up. He went; the letter was presented, and after considerable debate, the terms being so moderate and couched in such plausible language, they concluded to come over and give themselves up. They did, the Spaniards taking the precaution to tie their hands as they crossed over. All of them crossed that same evening, slept tied and next day were unmercifully slaughtered. The whole number slaughtered was 279. Having killed all the men, next day they started on their way back with all the families afoot. On the 2nd day thereafter, Dn. Manuel Serrano, Capt. under Elizondo, who felt grieved at the barbarious manner in which the men had been killed, deliberately walked into Elizondo's tent, shot him dead and started towards Perez's (shot at and missed him) tent with the same view, but was apprehended and prevented from doing further mischief. They tied him and brought him to San Antonio, a raving maniac. They arrived here about the 22nd of September, about 10 A. M. and formed all the captives, women, in a line on the main square. The line being formed, Arredondo in full uniform, with his staff, came in front of the line of captives and asked who was the Mexican Aunt. When he said this, Da. Josefa Nu�es de Arocha, wife of Francisco Arocha, answered "Here I am Nephew." Arredondo then said, "So you have offered $500 for my paunch to make a drum with?" "Yes. I have and would have made it, had I got it," she answered. "You could not obtain my paunch," said he, but now I can punish you as you deserve. You can go and rest at the Quinta, to make tortillas for my men and me. "I would rather you would give me fifteen shots, than that it should come to this." said she. Upon this Arredondo gave the order that the captives should be taken to the Quinta. Arredondo [was] kept in command in San Antonio, until the month of November. when he was called to Mexico. On the 8th of December, 1813, the Estremadura regiment, 800 under the command of Col. Benito de Armenan entered San Antonio. They did not seem to be other than devils. They stole and committed many things. Armenan remained in command here until November. 1814; when he was ordered to Chapala. where his regiment with the execution of about thirty-five were killed; Ygnacio Perez remaining in command here. In 1816, Manuel Pardo relieved Ygnacio Perez. In 1817 Manuel Pardo was relieved by Antonio Puertas. In 1818 Antonio Martinez relieved Antonio Puertas. In 1819, on the 5th of July San Antonio was inundated by a flood, in which twenty-eight persons were lost. On the 25th of same month, Antonio Menchaca, being a soldier of the King of Spain, took the message to Col. Galica that Mexico was independent of Spain. The privations were such in 1814, by reason of the City being surrounded by Indians, the people being unable to go out of the town, that a sack of corn was sold at $3.00; a lb. of coffee, $2.50; sugar, $1.50; tobacco, $1.00 per ounce. The people being in such pressure, would at the risk of their lives go out in the country to kill deer, turkey, etc., and cook herbs for the support of their families. They remained there till planting time in 1815, in which year in San Antonio there was not a single horse belonging to the Military service. Detachments or squads of fifteen soldiers had to be sent afoot as far as the Leona, to receive the mail from Mexico. The persons who were engaged at agriculture, had to go in squads of fifteen to twenty or more to look for their oxen; and while working had to keep their arms with them. There were so many Indians around the city, that one enemy, while yet light, a lady while sitting at her door, where, M. S. factory in the City, was killed by a Twowakano, who walked up to her and shot her in the head. In the same month another lady was killed at the Alamo, by a Twowakano, and Domingo Bustillos, who was coming from the Alamo Labor in company with three others was shot in the shoulder. It may be counted as a miracle, that no more deaths occurred than there did; because the Indians would dress themselves with the clothes of their victim, and would promenade the streets at will. The people lived with this dread till the year '20, in which year, the Comanche, and other tribes of Indians came to San Antonio, to make peace, which was granted them, but notwithstanding this, they would still kill and rob the settlers. The people had to be on the alert continually; for when the Indians got a chance they would kill and rob them. Very few of the people had milk cows, for the Indians had not given them a chance to raise cattle. When the Indians came to seek peace, a good many of the settlers bought horses from them. In 1822, Jose Felix Trespalacios relieved Antonio Martinez from the command. During the command of Trespalacios, San Antonio, underwent a great change for the better; money circulated more freely, until 1825, when a provincial govt. was established, governed by six cavaliers, until it was determined that a political chief should be named, the nomination of which, fell upon Dn. Antonio Saucedo. He governed as political chief two years, after which Ramon Musquiz was elected. In 1826, the regiment of Mateo Aumada, a Mexican, arrived here. He remained as Military Commander until 1828, when Gen. Anastacio Bustamante, and Gen. Manuel Theran [Teran] arrived. On the 6th day after their arrival, Gen. Theran, at the head of Aumada's regiment started for Nacogdoches, to suppress the Americans, where [they] were reported to be making preparations for fighting. They arrived at night, and found everything, to all appearances, quiet. There on seeing that everything was quiet, left Aumada in charge of the troops, and he, with a body-guard went to the Sabine river, and finding all quiet there, returned to N. In 1830 Theran came to San Antonio and left Aumada in command at N. In 1830, in March, James P. Bowie, of Kentucky, came to San Antonio, in company with Gov. Wharton. From here, Bowie went to Saltillo. In the same year J. M. Veramendi was appointed Lt. Gov., and started for Mexico to qualify. There Bowie and him met and became friends. Veramendi came back with his family and Bowie accompanied him. Bowie and Ursula Veramendi, became engaged; arrived at San Antonio, and Bowie, not having what he considered enough to justify him in marrying, asked Veramendi to give him time to go to Kentucky and get funds, and he would then marry his daughter. Veramendi granted the request. Bowie went and returned in the month of March, 1831, and married; remained three months here, then left for the interior of Texas to recruit forces for the war. Returned in 1832, went to look for the S. Saba mines; returned remained here four months; again went to look for mines. While Bowie was on this second trip, news reached here that Letona, the Governor of Mexico, had died. Veramendi had to go to Mexico to take charge of government. While Bowie was on the Colorado, he received a command from San Felipe, directed by Austin, that he should repair immediately to S. F. that his services were greatly needed. Upon receipt of this news, Bowie wrote a letter to his wife, telling her where he was going and on what business and that it was hard to tell when they would meet again. Veramendi, having heard of Letonia's death, made ready for his trip to Saltillo, started and arrived there on the 11th of November, 1832. As soon as he arrived, he received his com. as Gov., which he exercised until the 7th of February, 1833, when Bowie with seven other Americans arrived there also. On the following day he had an interview with Veramendi, and was introduced to the members of Congress. As soon as his acquaintance with the leading members became such as to warrant it, he told them what his object was. He received the assurances of Marcial Borrego and Jose Maria Uranga that they would aid him his enterprise. He tried, and succeeded in making them change the Congress from Saltillo to Monclova. Congress having been established at Mexico, he returned to Texas. In the same year, in the month of July Veramendi sent $10,000 to Musquiz to be sent to N. O. In the month of September, Veramendi's family as well as Bowie's wife, with $25,000 worth of goods were taken to Monclova, where they arrived on the 27th of September. On that day the cholera commenced there. The first who died of it being Madame Veramendi; then Madame Bowie, the balance of the family remained there until the lst of November, when they were brought to San Antonio by A. M., when they arrived. The year 1834 passed; also 1835, in which year in July, Col. Nicholas Condelle, with 500 Infantry and 100 Cavalry, arrived here; for it was reported that the Americans were gathered at S. Felipe. With these last troops there were here 1,100 soldiers, 1,000 Cavalry, and 100 Infantry. On the 23 of October, A [ntonio] M [enchaca] received a letter from Bowie in which was enclosed a note addressed to Marcial Borrego and G. M. Uranga. The letter told A. M. to deliver the note in person, to trust it to no one; and to be as quick about it as possible. He went, while the report here was that the Americans were at Gonzales, delivered the note, and on his return got as far as San Fernando de Rosas, where he was detained and would not be allowed to pass; though his liberty was given him upon his giving bond. Six days after the capitulation of San Antonio, a friend of his, Pedro Rodriguez, furnished him with two men and horses to bring him to San Antonio. He crossed at night at Eagle Crossing, and arrived here on the 20th of December. The companies who had assisted in the siege were still here. As soon as he arrived here, he sought Bowie, who as soon as he saw him, put his arms around his neck, and commenced to cry to think that he had not seen his wife die. He said "My father, my brother, my companion and all my protection has come. Are you still my companion in arms?" he asked. Antonio answered, "I shall be your companion, Jim Bowie until I die." "Then come this evening", said Bowie, "to take you to introduce you to Travis, at the Alamo." That evening he was introduced to Travis, and to Col. Niel. Was well received. On the 26th December, 1835, Dn. Diego Grant left San Antonio, towards Matamoros, with about 500 men, A's and M's of those who had assisted in the siege. They here kept up guards and patrols of night. 250 men went from here to keep a lookout on Cos who had gone to Mexico, and returning here on the 5th January, 1836. On the 13 January, 1836, David Crockett presented himself at the old Mexican graveyard, on the west side of the San Pedro Creek, had in company with him fourteen young men who had accompanied him from Tennessee, here as soon as he got there he sent word to Bowie to go and receive him, and conduct him into the City. Bowie and A. went and he was brought and lodged at Erasmo Seguin's house. Crockett, Bowie, Travis, Niell and all the officers joined together, to establish guards for the safety of the City, they fearing that the Mexicans would return. On the 10 February, 1836, A. was invited by officers to a ball given in honor of Crockett, and was asked to invite all the principal ladies in the City to it. On the same day invitations were extended and the ball given that night. While at the ball, at about 1 o'clock, A. M. of the 11th, a courier, sent by Placido Benavides, arrived, from Camargo, with the intelligence that Santa Ana, was starting from the Presidio Rio Grande, with 13,000 troops, 10,000 Infantry and 3,000 Cavalry, with the view of taking San Antonio. The courier arrived at the ball room door inquired for Col. Seguin, and was told that Col. Seguin was not there. Asked if Menchaca was there, and was told that he was. He spoke to him and told him that he had a letter of great importance, which he had brought from P. B. from Camargo, asked partner and came to see letter. Opened letter and read the following: "At this moment I have received a very certain notice, that the commander in chief, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, marches for the city of San Antonio to take possession thereof, with 13,000 men." As he was reading letter, Bowie came opposite him, came to see it, and while reading it, Travis came up, and Bowie called him to read that letter; but Travis said that at that moment he could not stay to read letters, for he was dancing with the most beautiful lady in San Antonio, Bowie told him that the letter was one of grave importance, and for him to leave his partner. Travis came and brought Crockett with him. Travis and Bowie understood Spanish, Crockett did not. Travis then said, it will take 13,000 men from the Presidio de Rio Grande to this place thirteen or fourteen days to get here; this is the 4th day. Let us dance to-night and to-morrow we will make provisions for our defense. The ball continued until 7 o'clock, A. M. There Travis invited officers to hold a meeting with a view of consulting as to the best means they should adopt for the security of the place. The council gathered many resolutions were offered and adopted, after which Bowie and Seguin made a motion to have A. M. and his family sent away from here, knowing that should Santa Anna come, A. and his family would receive no good at his hands. A. left here and went to Seguin's ranch, where he stayed six days, preparing for a trip. Started from there and went as far as Marcelino to sleep; then three miles the east side of Cibolo, at an old pond at sun up next morning. Nat Lewis, passed with a wallet on his back, a-foot from San Antonio, and A. asked him why he went a-foot and he was answered that he could not find a horse; that Santa Anna had arrived at San Antonio, the day previous with 13,000 men. A asked what the Americans had done. He said they were in the Alamo inside the fortifications. A. asked why N. did not remain there and he answered that he was not a fighting man, that he was a business man. A. then told him to go then about his business. A. continued his journey, got to Gonzales, at the house of G. Dewitt, and there met up with Gen. Ed Burleson, with seventy-three men, who had just got there, then, slept. And on the following day, attempted to pass to the other side with families, but was prevented by Burleson, who told him that the families might cross, but not him; that the men were needed in the army. There met up with fourteen Mexicans of San Antonio, and they united and remained there until a company could be formed. The Americans were gradually being strengthened by the addition of from three to fifteen daily. Six days after being there Col. Seguin, who was sent as courier by Travis, arrived there and presented himself to Gen. Burleson, who, upon receipt of the message, forwarded it to the Convention assembled at Washington, Texas. On the following day, the M. Co. was organized with twenty-two men, having for Capt. Seguin; 1st. Lt. Manuel Flores, and A. M. 2nd. Lieut. On the 4th of March, the news reached that Texas had declared her Independence. The few that were there, 350 men swore allegiance to it, and two days after, Gen. Sam Houston arrived there and received the command of the forces. When Santa Anna took the Alamo and burned the men that he had killed, he ordered, Madam Dixon [Dickinson] (Travis' servant and Almonte's servant) a lady whose husband had been killed in the Alamo, with propositions to A. or to those desiring to make Texas their home. The propositions were in these terms: All American Texans, who desires to live in L. will present himself to Gen. Santa Anna, will present his arms, and he will be treated as a gentleman. When the Americans understood what they proposed, they in a voice cried, "General Santa Anna, you may be a good man, but the Americans will never surrender," "Go to H ... and hurrah for Gen. Sam Houston." On the following day, the Texan spies arrived with the intelligence that the Mexicans were on their way to Gonzales; that they were encamped on the Cibolo. On the same day the Americans started for the Colorado river, and slept on Rock Creek. On the following day, at La Vaca, where Col. Hawkley [Hockley] with 160 men, reported to Gen. S. Houston for orders. On the next day, they encamped on the San Antonio, and there Gen. Summerville presented himself, with 250 men. From thence they started and arrived at Mr. Bonham's on the Colorado, and there remained ten days. On the 6th day after they got there, Gen. Ramirez, y Sezma, of the Mexican side with 400 presented himself. There were 900 Americans in camp. As soon as the Americans saw that the Mexicans were trying to draw them into an attack, the Americans got in readiness for attacking, but Houston told them that not a single man should move out, that that move was only made to draw him out and ascertain his strength, something which he did not intend to let them know. The Americans murmured against that course, whereupon, Houston told them that such was his determination and that nothing should tempt him to depart from it; but that if they were determined to do otherwise, then all they had to do was to choose some other commander, for he would not take the consequences upon himself, that he then would fight as a private, but never as a commander. The soldiers upon seeing this, saw that it was useless, and gave in. They then started for the Brazos River, with the intention of crossing at "La Malena Crossing" of the river which was at the crossing of 'the Nacogdoches road, about eight leagues above S. Felipe de Austin, and arrived there in two days, after and took a position in the bottom on this, W. side. From there he sent M. Baker, in command of 250 men, to go to S. Felipe, and take all they could from the stores and burn the balance. Baker, with his men went to S. Felipe, crossed the river, encamped in the bottom, and then commenced to haul all they could away from S. Felipe and to hide it in the bottom until Baker told them that he could wait for them no longer, to burn the stores, which they did. While the stores were being burnt, a great many barrels of liquor that had been crossed over were ordered to be broken, and it was done. While this was being done the American spies came on the opposite side and told Baker that Houston wanted him to come back, that the Mexicans were on the march, and were then at S. Bernardo. Baker immediately set out to join him. Arrived at Groos' house on following day, and there, Baker was ordered to remain till further orders. On that same day the steamboat, Yellow Stone, Capt. L. G. Grayson, came up the river, and Houston stopped it and told the Capt. that on his return, he should stop there to await his orders, which he did, and remained there twelve days. The Mexicans, the greatest part of them, turned to Ft. Bend, only 500, going to S. Felipe crossing. On the 18th day that H. was in Camp, Santa Anna, with 700 men crossed at Ft. Bend towards Galveston. He was seen by an American, who took the news to H. The American arrived at Groos' at about 5 o'clock, P. M. his horse very much fatigued, and had ridden another horse to death. He gave H. the news, and on the following day H. began to cross his troops on the steamboat. After crossing, the Americans, went as far as Isaac Donoghue's house to sleep. On the following morning at about 8 o'clock, Col. Bell, Col. Allen, and Mirabeau B. Lamar, with 54 Americans, presented themselves to Houston for duty. From there started and slept on the edge of the pine region, and on the following morning an old man in company with a young one arrived at camp with the word from Santa Anna to the effect that where were the A. that very oak produced six A. H. replied that though he did not have many men, but with what he did have, he would surely call upon San Antonio. Started from there and arrived at the head waters of Buffalo Bayou, on the west, where camp was pitched. As soon as camp was established, H. sent 25 horsemen to reconnoiter and see what was going on. The horsemen found that Santa Anna had crossed towards Harrisburg. They took two couriers, one from Musquiz of San Antonio, and the other from Mexico, which were taken to H. Gen Rusk called the Mexican officers to read the messages. It happened that A. opened the official dispatch from Gen. Felizola to Santa Anna in which the former said that he sent S. A. 800 choice men, for he had heard from a reliable American that the Americans were 6000 strong, and that he awaited instruction from Santa Ana in order to know what to do. As soon as H. heard this he said that he did [ n't ] care a cent for the Mexican disposition, that all he wanted to know was where S. Anna was; that now he was separated from the main body, he felt confident he could defeat him. H. then gave orders that 200 men should be placed under the command of Capt. Splinn to guard the horses, and equipage which was to be left there by the Americans. and they to go next day and overtake S, Anna. Gen. Sherman, then said that his orders would be obeyed, and immediately started to select the Co. that were to remain. Houston told Sherman to have the M. Co. left at camp, that they knew but little about fighting, but were good at herding. Gen. Sherman then went to M. Co., and asked for Capt. Seguin, and he was told he was not there. Then Sherman said to A. M. that as soon as he came to tell him that his Co. was ordered to remain and guard the equipage and horses. A. M. asked him why his Co. was to remain, and was told that those were his orders. Seguin came and was told what Sherman had said, and Seguin asked A. M. what he (M) thought about it. A. M. said that he wanted to go and see H., and both went. They got to H. and saluted him and H. asked what was wanted. A. answered that Sherman had given him orders to remain in camp, and he wished to know why it was. H. answered that as a Gen. he had given that order. A. then told him that he could not deprive him of his command, but that when he joined the Americans, he had done so with a view of aiding them in fighting, and that he wanted to do so; if he died he wanted to die facing the enemy; that he had not come for herding horses and was not going to do so, that if that was the alternative, he would go and attend to his family, who was on its way to Nacogdoches, without servants or escort. H. then said that A. spoke like a man. A. answered that he considered himself one, that he could handle any and all kinds of arms from a gun to an arrow, and that having a willing heart he did not see why he should not be allowed to fight. H. then told A. that he would gladly let A. and his Co. go to fight. On the following day after breakfast, (19th April, 1836) the army was collected and were addressed by H. and Rusk. H. spoke very eloquently. He dwelt along and pathetically upon the suffering of those who had fallen at the Alamo, and upon those who fell at Goliad, under Fannin. H. having concluded, Rusk then addressed them with such force and effect as to make every man, without a single exception, shed tears. When general Rusk concluded speaking, provision was made for crossing the bayou, which was done by making rafts on which the guns, two four-pounders, were crossed, and also the horsemen. It took until five o'clock of the 19th of April to get over. The march was continued until ten a. m. of the 20th. The men slept on their arms and proceeded very early the same morning to [the] bridge at Harrisburg, and at 7 o'clock a.m. crossed it. We halted on a hill to await reports from spies. The spies came and reported that Santa Anna was within one and a half miles from there. Upon hearing this, General Houston ordered that the troops should discharge their arms and clean and reload for, he said, the time was close at hand when they would be needed. After this order was complied with, the Americans moved forward to a bend in the bayou, where they were halted in line. They were ordered to lie down and cautioned not to shoot a shot until ordered to do so. Shortly after the Americans were on the ground, three Mexican companies came in sight, shooting scattering shots to draw the Americans on, for they could not see the Americans. When the Mexicans saw that no one answered their shots they halted and an officer came and ordered them back. They remained about half an hour without shooting and General Houston ordered General Sherman to advance with cavalry and ascertain what the Mexicans were doing. Sherman did so. As soon as he reached the spot indicated the Mexicans attacked and wounded two of his horses badly. Sherman ordered that those men whose horses were wounded should be taken up behind two others, and he retreated in good order. The Mexicans, about forty, followed the Americans, and when they came in good range a gun was fired at them which killed some eight or ten, and they retreated. When they reached the mott they commenced to shoot at the Americans with yangers. Houston gave orders that those men who lived upon the Navidad and Lavaca and killed deer at a hundred paces offhand should come forward and take a shot at the Mexicans. Immediately about fifty men were formed in line and went to a good distance from where the Mexicans were, fired one volley and hushed them. General Houston, seeing that the Mexicans fired no more, after some time elapsed, sent some men over to find out if the Mexicans still occupied the mott and they found no one there. As soon as this report was brought to the general, he sent a detachment of one hundred men to occupy the place and to let a man climb a tree and see what the Mexicans were doing. The sentinel on the tree reported that they were cutting timber and fortifying from point to point the space upon which no timber grew. The hundred men were relieved by another hundred men until three o'clock of that day, at which time Houston ordered the line to be formed where the troops had first lain down. He then gave Sherman command of three companies of infantry and Lamar the command of the cavalry, with orders to advance and ascertain what the Mexicans were doing. When Sherman got to the edge of the prairie he ordered his companies to fall flat, the cavalry going out. The Mexicans, upon seeing the American horse coming out with his cavalry engaged them. When the Mexicans observed that the Americans would not retreat, they sent some infantry to support their cavalry. Upon this, Sherman ordered his men to the relief of the horse, upon which the Mexicans retreated. In this skirmish three Americans were wounded, Colonel Neil and two others. The Americans under Sherman and Lamar then came over to where Houston was. Fifty men were placed on guard on the American side that night. On the 21st early in the morning, about ten or twelve Mexican mules were in sight of the American camp and were driven in by the Americans. At about ten o'clock the spies came in with their horses very tired and told General Houston that Coz had crossed with eight hundred men and had burned the bridges; that if he wanted to trouble them he could do so, as they were then close by; but Houston said no, that they were his anyhow, to let them rest. About 2 o'clock of the same day, H. ordered the troops to form in line, in three divisions, the right wing under Rusk, left to Sherman, and the Center, himself. When they were so arranged, he called the officers together to give them his instructions, and, after having done so told them that all the army should move at the same pace that he did. He then ordered Sherman to advance with his division to Santa Anna's right, and that Lamar should march along with him (H.) The attack was made, the battle began, the Mexicans taken by surprise, so much so that 11 rows of stacked arms were not touched; the fight lasted two hours and a quarter, wheu those who were not killed, taken prisoners or wounded, fled in great disorder. On the following day, Santa Anna was brought in by two Americans, a Lt. and Louis Robinson of Nacogdoches. He was found in the woods, under the care of two mulato girls. He was taken to Houston and many were in favor of putting him to death. But as he was a Mason and the most of the officers were Masons, he was protected. Next day, a steam-boat from Galveston, arrived with 300 men; four guns and provisions. Houston ordered that the provisions be divided into two equal parts, one for his troops and the other for prisoners and wounded, which was done. On the next day Dn. Lorenzo Zavala, arrived and spoke to Santa Anna, abused him very much. Orders were given that Sherman and Burleson with 250 men should march down to Ft. Bend, to see what Felizola who was with the main body of the Mexican troops, determined upon. When they got to Ft. Bend, they found that Felizola had left for Matamoros. They then crossed there arrived at a lake; remained there the balance of the day. At about 3 o'clock, P. M. Gen. Ampudia came into the American camp and asked permission to take all the wounded and sick away from there. He was told that he could do so and would not be molested. Two men with two horses loaded with roasted meat and gourds of water for the wounded and sick were sent with Felizola. He took them with him and overtook main body at Colorado river. SONS OF DEWITT

COLONY TEXAS |

FOREWORD

FOREWORD