SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

Page 2 Previous page 1 Santa Anna Manifesto (continued) Few of the colonists, if any, have taken part in this war, as I have stated before, and even the greater number of them found themselves forced to abandon their homes and set fire to them against their will. This is an evident fact known by the whole world. At B�xar and the Alamo a great number of the armed adventurers from New Orleans had perished, and it was not possible that those that remained could equal in number the army under my command, composed of six thousand men. The aim of the Texans was, and should have been, not to risk in a single battle the success of their undertaking which from the second of March was, openly and without disguise, independence. The character of the country, on the other hand, favored this type of warfare, one that among ourselves, during the first struggle for independence, gave such happy results to our small number, enabling a handful of poorly clad and undisciplined sharpshooters, with no other advantages than their acquaintance with the country and its fastness, to take immense trains of provisions and to hold in check for months at a time large divisions of the Spanish army. The memory of this fact, always present in my mind, and the necessity of always choosing dispatch rather than any temporary advantage, which I believe I have, proven, determined me to divide my forces, after the capture of the Alamo, since our numbers permitted it, but in such a way that each division in itself should be able to cope with the enemy, whom I believed and now know positively, could not be numerous. Without a fleet to cooperate with the army, to guard the coast, and to prevent the enemy from retreating or from receiving aid, the troops under my command had to supply this deficiency, and it was neither prudent nor plausible that, in order not to divide our forces, the coast should remain unprotected and the army flanked on the right by the enemy. The other alternative was for our whole force remaining together, to attend to this necessity, in which case without avoiding. the evil, the war would be prolonged by the ponderous march of our troops, all in a body. Our army would have suffered numerous losses on account of the prevailing sickness in the coast region, especially during the last April; and finally, as a result of this and the small bands of the enemy who would have constantly harassed our left flank, all our soldiers would have perished, uselessly fatigued by the hardships. If the army was to move always as a unit, it would have been possible only by going from B�xar to Gonzales to cross the Guadalupe at that place, then to the crossing of the Colorado at the place where Se�or Ramirez Sesma and I crossed it, then to San Felipe de Austin in order to cross the Brazos. But, in spite of the fact that by this means both our flanks and the coast remained constantly exposed and our march would have been extremely slow, it left Goliad as a rallying point for the enemy, who, reinforced, would have fallen upon my rear guard. Our troops, finding themselves faced on the front by those, swollen and impassable rivers, on their flanks by skirmishers, and on their rear by the enemy, who, perhaps, without offering formal battle, could still cut off our retreat and our land communications, left us without a port to our name through which we might receive supplies. What would have been the fate of the army then? At present it has suffered only a partial defeat while in search of victory and while trying to force the enemy to fight, a common occurrence in the hardships of war. Had it adopted another policy as a result of a childish fear of dividing its forces when its numbers permitted it, all would have perished of hunger or by the lead of invisible enemies. It is not the division of an army as executed by me under the circumstances explained and for the reasons presented, that prove the inefficiency of which I am accused. I repeat that I am not in favor of discussions in councils of war to determine military operations. Thus, the object in dividing the army into three divisions was no other than to facilitate the rapidity of its marches, to protect it from the guerrilla bands, to insure our flanks, to expedite our retreat, to secure food supplies through the ports, and to destroy any enemies that might appear. This policy was successful as far as the Brazos, where, having accomplished our purpose, the army should have been reunited in order to fight the enemy who was fleeing, and was to be found only on our front. Where was the mismanagement? There were troops and there was courage. The organization of our army enabled it to use its courage successfully; its plan, its system, its order, and the cooperation of its divisions succeeded in making the enemy flee out of sight upon hearing of our approach; our troops, amidst privations and hardships, were infused with an unlimited enthusiasm that made them conceive an utter disdain for an enemy whom it had defeated and the remnants of which, after great threats and boasts and in spite of their large stature and heavy rifles, did nothing but flee constantly after the Guadalupe was crossed. The means adopted insured our communication with the interior, the receipts of our food supplies through the ports, and cleared the whole country of enemies between the San Antonio and the Brazos. The organization and the division of the army accomplished all this in the short space of a month and a half, since on the 15th of April, they should all, or the greater part of them, have been reunited at San Felipe de Austin. No means have been spared to represent me as a being so unreasonable as to risk the greatest interests of the country in unadvisable and rash operations. For this reason before going any further, it is necessary to review the position of the two belligerents on that very 15th day that has been chosen for my incrimination. The enemy we were going to fight was facing the army; B�xar, Goliad, and El C�pano on the route to the San Antonio River; Gonzales and Victoria on that to the Guadalupe; and the Colorado was guarded by the detachment of Matagorda. All of them could help each other and receive reinforcements from the main army in the remote case of an attack by the enemy should it be reinforced by a landing on the coast, a contingency that their reduced navy, the small number of their forces, and the growing need of their concentrating made most impracticable. Therefore, whatever the distance may be between various points and San Felipe, it cannot be said with justice that it is inadvisable for an army to cover the most important points of the country left in the rear with more or less numerous detachments. Otherwise, it would either have had to abandon them or have had to remain all together at the first place occupied---B�xar in this instance. The war we were engaged in was, from its very nature, offensive. Can it be claimed that the detachments should have been smaller? Would it not have been thought then that they were in a precarious situation? It has been necessary to criticize and all censure has, of necessity, been directed against me. When the concentration of the army was necessary, as it appeared to me at the crossing of the Colorado, in order to help General Sesma, I issued orders for that purpose and it could have been accomplished with ease. As it was not necessary, however, the army did not remain so widely divided as it has been made to appear by exaggerating the distances in our case (and minimizing them in regard to the enemy). Senor Gaona should have been at San Felipe on the fifteenth and Senor Urrea at Brazoria or Columbia, leaving a garrison at the port of Matagorda. Thus, the position of the army on that day should have been as follows: Generals Filisola and Gaona at least as far as San Felipe; Senor Sesma at Thompson's Crossing, a distance of twelve; not sixteen, leagues from the first at the most; and I on the road to Harrisburg, twelve leagues from Thompson's Crossing. If General Gaona lost himself in the desert from Bastrop to San Felipe can that accidental misfortune be argued as proof of the mismanagement of the army? And if General Urrea, either for the same reason or some other excusable cause, was not able to be, at Columbia as it happened, can a general be accused of not having a plan, just because he is unable to carry it out as the result of circumstances foreign to his will and not easily foreseen? My orders were responsible for the concentration of the army after the twenty-first of April. Because of them General Gaona was at Thompson's Crossing by the twentieth and General Urrea was at Brazoria on the same day, part of his division having advanced as far as Columbia. Therefore, on that day the position of the army was this: Generals Filisola, Gaona, Sesma, Tolsa, Woll, in a word, all those that on the twenty-fifth were at the house of Mrs. Powell at Thompson's Crossing (except General Urrea), were six leagues distant from Columbia and twelve from Brazoria where General Urrea himself was, only ten from New Washington (which is only fifteen from Thompson's) where I was. Why was not this day chosen to point out the scattered position of the army? The operation undertaken against Harrisburg, besides being necessary and urgent, as I have pointed out, had been viewed by me in the light of its full importance in case of success. When this was frustrated, believing myself obliged to attack the enemy without waiting for the concentration of the army previously arranged, I foresaw all the contingencies .as we shall soon examine. The enemy had occupied the thickest part of the woods at Groce's Crossing since before the fifteenth with a force not exceeding eight hundred men, fearing to be attacked every, minute, and it had a few detachments, very small in number, in addition to those at the crossings of San Felipe and of Thompson, at Velasco, which I ordered occupied, and at Galveston. Evident proof of its weakness and reduced numbers was the abandonment of the chief officers of the government of Texas at Harrisburg, which, for that very fact and various others, it should have held and defended as the capital if it had had sufficient forces; its failure to attack the divisions of our army on the fifteenth, as Houston could have done with mine, the force under my command being made up of a little more than seven hundred men, including fifty, not seventy, mounted troops of my escort and the artillery men of a six pounder that I had; likewise the divisions of Generals Filisola and Gaona could have been attacked; the abandonment of a point as important as New Washington worthy of being protected not only as a port but still more because of the considerable deposit of all kinds of supplies, especially food, that was located there and which was taken by Colonel Almonte; lastly, the irrefutable news from all sources that confirmed the flight of the Texan troops toward the Trinity. Was it likely or credible that they could be so numerous as it has been incorrectly supposed, to the extent of giving them as much as two thousand men? Was it proper to stop or to retreat in our advance even if that had been their number? It was not, therefore, an inordinate desire for glory nor an immoderate impatience for it that determined my operation against Harrisburg and made me direct it in person after serious consideration. I had more than seven hundred men and, supposing that Houston had eight hundred, I believe our soldiers, chosen soldiers such as I had, were able to fight and to overcome eight hundred Texans. If national pride blinded me, I believe that it is excusable, especially since from this error of mine no serious consequences followed but rather with that very force, I was able to fight the enemy on the eve of our misfortune. The blow upon Harrisburg failed. The enemy having fled and New Washington being occupied by Colonel Almonte, I considered that if they attempted an attack upon New Washington from Lynchburg, Colonel Almonte by himself would be in a precarious situation, and I marched to his rescue. But in spite of the relative equality of our forces, I may almost say superiority, I did no want to risk a battle, so I asked, as I have stated before for a reinforcement of five hundred picked men with which I would have outnumbered by one-third or more the enemy troops. Was there lack of foresight as it has been .supposed? In view of Houston's march communicated to me by the advanced guard at Lynchburg I was now in a position to choose the location for battle; and I shut up the enemy in the low marshy angle of the country where its retreat was cut off by Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto. Their left was opposed by our right, protected by the woods on the banks of the Bayou; their right covered by our six pounder and my cavalry; and I myself occupied the highest part of the terrain. Is this position compatible with the fatal lack of foresight of which I am accused? Everything favored our country and the cause which we were defending in its name. Lastly, in order that nothing be lacking to our good luck, the enemy was repulsed in a skirmish on the evening of the twentieth, and it did not believe that the troops brought by General C�s were really reinforcements, but took them to be a ruse by means of which we were trying to make our troops appear larger by causing a detachment sent out the night before to march back to camp.

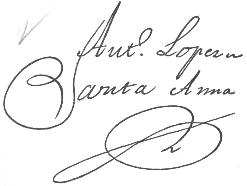

It was fate, therefore, and fate alone, that dipped the wings of victory that was about to crown our efforts. Though I do not flatter myself that my operations are above reproach, in spite of what has been briefly stated, I do not believe that persons of judgement and sane criteria and thinking military men who are free from bias will fail to admit how unfounded have been the charges by which it has been attempted to represent me before the world as a conceited and overproud general, without knowledge, without a plan, without foresight, without caution, and, in a word, without any of those qualities that adorn a military leader of my kind, who, in other campaigns, has known how to be victorious; but whose name, now that misfortune has placed his very life in jeopardy, is dishonored, while the nation that confided its defense to him is accused of having exercised little judgment at least in so doing. We were overcome at San Jacinto, and I was taken before the chief of the Texans, Houston, on the 22nd. I endured untold sufferings of all kinds but, as I have had the sorrow of learning, only by ending my life could they have placed me beyond the recriminations of my fellow-citizens. In their opinion, the tomb was the end pointed out by honor; and, at the same time that I am accused of being daring and imprudent I am accused of being pusillanimous to the point of treason just because I still live and breathe the free air of my country. They expected of me more victories, and, misfortune having overtaken me, death should have been my glorious end. This optimism, for which we look and which we expect of others in whom we criticize anything short of sublime romanticism---if I may be allowed to use this expression---more than once, has led us into error; and perhaps this shall not be the last time that it carries us to the brink of injustice, all the less palpable, axed for that reason more dangerous as the principle on which cur blindness rests is the more noble, the more heroic. As the extremes usually meet, since I was not a tragic hero in my misfortune, I am branded as a traitor. The distance between one and the other is immense. I have not risen to the superhuman virtues of a God, neither have I sunk to the depths of perpetrating a crime, the most horrible that can be committed. Let the distance be measured impartially and I will have been judged correctly. It is a great consolation for me, however, that the prejudice of my fellow-citizens should rest in part on false appearances that I myself have partially been obliged to create. But by assuring them, now that I am free, that I am not bound by dishonorable treaties against my country, I have dissipated those appearances by confirming the truth. If after explaining my acts and the circumstances that determined then, suspicion and calumny still excite their venomous tooth against me, it is not for me to prove their error. I shall not be able to disprove a negative, the very nature of which is not susceptible of proof. Time alone shall bear the evidence and I would intrust my justification to its care, having no other friends in my defense, if, as I have already said, I did not owe an explanation of my actions to my country and to my honor. The first duty during my imprisonment was to demand the treatment and considerations due a prisoner of war. The word talon which I overheard Houston utter made me enter into a discussion, to draw a parallel, daring as it was in my position, as to the justice of the war and its character as waged by both belligerents, M�xico and the Texans. The son of Don Lorenzo Zavala was serving us as interpreter and finally their effrontery went as far as to demand the practical surrender of the entire army under my command. The idea .was as preposterous as it was highly, offensive to our national honor, and my indignation must have been shown so clearly in my face that Houston himself blushed and changed the nature of the proposal, contenting himself with the retirement of the army. Do not think that I pretend to assume greater importance than that to which my position as general-in-chief entitles me. I foresaw that my troops, on account of my imprisonment, would experience a discouragement that would need much tact to dispel. Never, however, did I imagine what happened. I tried to make the best of the situation which doubtlessly was to save the lives of my companions and mine from the present misfortune the danger of that first moment of exultation, and to give the troops that made up the army time to decide upon a plan mature operations. It was apt to me that if, in the instance of confusion that a misfortune of such dimensions of San Jacinto produces„ the operations of our troops were suspended, the heart of the soldier, reacting to the honorable idea of avenging the recent insult, convinced that both justice and superiority were on his side, a new attack upon the enemy could and would be attempted successfully. At the sight of a force three times larger, such as could have been mustered, and by virtue of an intimidation that should have been practiced but was not done, our lives undoubtedly would have had to be spared. Having been abandoned to the clemency and interested motives of our opponents, such a thing seemed incredible, though our lives were actually spared. Nevertheless, the retreat of General Filisola could have had no other origin than a concept on this point diametrically opposed to mine. Thus in his reply to my communication of the 22nd he said that he was acting only out of consideration for the safety of my person, a desire to save my life and that of the prisoners, although he realized the advantages that might befall our army from a continuation of hostilities. So noble a motive, as this must have appeared to me, was engraved with indelible gratitude upon my heart. Although afterwards that general, in view of the public disapproval of his movements, has attributed his actions to other causes, the only true one is, in my judgment, the former; and a respect for this would keep forever within my heart my opinion upon the matter had not my honor been offended afterwards by attributing the sad plight of the army under my command to other causes. Much, importance has been attached to the lack of resources. I am ashamed to admit that, because of lack of food, it was not thought advisable to undertake a march upon San Jacinto by an army that was sixteen leagues distant, an army that has always been justly admired for its endurance of all kinds of privations, though it had meat and other provisions in abundance and was also expecting to receive others, that, if not of fine quality were sufficient to keep it from starving. It had, however, enough for a retreat as far as Matamoros, that is to say, to retreat almost two hundred leagues. Two days would have been sufficient for the forces gathered at Thompson's alone to have given a blow to the enemy that would have repaired easily the misfortune of the 21st, leaving us to protect the crossing, or if the entire army wished to be concentrated by ordering the said general to cross the river at Brazoria. The position of the army beyond the Brazos would have been exempt from the obstructions presented by the country on its retreat after the rains of the 27th, by which time the enemy should have been destroyed and the food that I brought from New Washington and that fell into its hands should have been in our possession. Even if for no other reason, this last one, in my judgment, should have decided the general that succeeded me in command to try an attack; and I flatter myself, even risking to appear presumptuous, that if I had been able to reach Thompson's as I wanted, victory would have returned to our troops within three days. It was not without surprise that I later heard the news of the retrograde movement so precipitately undertaken contrary to my real desire. Allow my self-esteem a comparison, the odiousness of which shall fall upon he who first made it The twentieth of April the greater part of the army that had crossed the Colorado was together. Two of its divisions were sufficiently numerous to have engaged the enemy and to help each other had it not been for a chain of unfortunate coincidences. We had, had food, munitions, and other war supplies in plenty and even in excess of our needs. We had been victorious in every encounter; our line was covered both on its rear and on its flanks. Yet the moment I fell a prisoner the army retreated, the food became short, our positions were abandoned and the army concentrated itself two hundred leagues from the place where it should have been and where it had left six hundred prisoners in the most complete abandonment, entirely to their own resources. When did the army fulfill its object and its duties better? I foresaw, therefore, the confusion of the moment among the troops of our army and I took advantage of tie opportunity afforded by Houston's proposal, succeeding, as I have already stated, in giving the said army the time necessary for its reorganization as the result of an armistice that I concluded but our troops used only to retreat unmolested.sdct All that was done in favor of the prisoners on the part of the general on whom the command fell was reduced to sending General Woll as emissary, not to conclude an armistice, or rather, to make one as it was proper, since a prisoner was the one who had drawn it up, but only to ask for instructions and to deliver the treaty in person. When that general was detained and treated without consideration for the mission on which he came, not even the slightest protest was made, and his treatment was completely ignored so that he had to depend only on the efforts of a general who was himself a prisoner to make himself respected. To that same general I gave instructions by word of mouth in order not to compromise him as to what should be done by the army according to my judgment In this I counted, of course, on the fact that the enemy was not going to allow itself to be robbed of its triumph, consequently I gave the said general a paper which stated that credence should be given to whatever he said on my part Nothing was thought of, however, except a retreat, their fear reaching such an extreme as to set free or allow the Texan prisoners that were in our army to the number of more than one hundred to escape without trying to arrange an exchange for those who had fallen prisoners at San Jacinto, and even abandoning our sick, in such a way that the proximity of the army, its actions, the dignity of its commander who should not have been discouraged by a mishap, everything in short that might have encouraged those who were prisoners and enabled them to raise their voice in defense of justice was wanting, and we were left to the mercy of the conquerors, an undisciplined mob although justly proud of so important but uncontested a triumph. ["I sent an order to General Filisola on the 22nd of April to set them free, but can it ever be thought that this order was to be carried out without even trying an exchange, though unsuccessful?" (Note of the original)--C.C.] In all justice it must be confessed, however, that the Texan general, Sam Houston, is educated and is actuated by humanitarian sentiments. I am indebted to him for a treatment as decorous as the circumstances permitted while he was in Texas, for my liberty after he returned from New Orleans where went to have a wound that he received at San Jacinto treated. There were, nevertheless, before this solution, transactions of which I am going to speak, the obscure aspects of which have been used by critics in order to defame me. The nation has seen in print the agreements that I signed at Velasco on the fourteenth of May revealed only as a disgraceful weapon against me by an infamous betrayer who served in the office of my secretary, taken up and published by the papers that carried on a most advantageous and disloyal war against me as conclusive and irrefutable proof that I sacrificed everything to the pusillanimous terror, the cowardly fear of death. Neither my previous constant service in favor of the independence and liberty of M�xico, nor those that I had just rendered in Texas, not obligatory on my part, were able to outweigh the opinion of my adversaries with regard to an incredible report. As the facts were presented without considering the circumstances, without being aware of the unheard of exactions demanded by the officers of the government of Texas, the agreements were regarded as uncalled for. In short, as duty to one's country is as delicate as the honor that dictates it, by playing upon this chord so highly pitched among my fellow-citizens it has been possible to make my name sound in their ears that had just listened to my proclamation as benefactor of the country like that of a monster of ingratitude and infamy. Nevertheless, to my part in the action of San Jacinto I have wished to add the principal testimony as to my actions after it, confident that the good judgment of my compatriots, once they rued it will save me the greater part of the painful task of vindicating myself which, in itself, would involve involuntary self-praise. The proposals that were transmitted to me by the so-called Cabinet of Texas have doubtless been read, and the sight of them have surely dissipated in great part, if not entirely, the immense amount of evil that was thought to be contained in the agreements of the fourteenth of May. The Directory of Texas, let us call it thus, arbiters of my life and of six hundred Mexicans, wished to see our entire expeditionary force lay down its arms and become prisoners; that Generals Filisola, Gaona, Urrea, and Ramirez Sesma be considered by me and obliged to admit themselves confessed prisoners of the Texans; that they sign with me their infamy by offering, though free, not to take arms against Texas. I converted this idea into a personal promise on my part of not making war, one from which no prisoner can save himself. It was desired that my influence should be used upon the entire nation, armed in so just a struggle, to make it lay down its arms. I changed this proposal to a negative, that is, I promised not to use my influence for the continuation of the struggle. But do the Mexicans need my guidance in order to have a country, to love it, and to know how to defend it heroically? They wished the independence of Texas to be recognized from that very moment and the limits fixed; that a petition by the army should force the government to approve this transcendental proposal, leaving to the nation only the negotiation of a treaty of commerce, the prisoners taken at San Jacinto to remain as hostages. I brought this daring proposal to an honorable conclusion for me, one free of embarrassment for the nation. I did not even try to implicate any of the officers of the army in the matter. I honorably refused to recognize Texas as a nation or to determine its limits. I showed, it is true, a desire to terminate the struggle through friendly and peaceful means but I left the government free to judge if it was suitable to the nation, for if the recent and fateful retreat of our troops did not give me flattering hopes in warlike operations, I did not wish that the hope of the nation should end with mine. I did promise to try to get a hearing for the Texas Commissioners, but this in itself did not bind the government to receive them, nor if they were received did it have to accede to all their pretensions. I, in short, gave no other guarantee of my promises than my personal responsibility, but not with the official character of President of the Republic, for I was nut acting in that capacity at flat time. Neither did I pledge myself as a plenipotentiary of the government, much less as general-in chief. My imprisonment, if I may express it that way, afforded me the one advantage of making it impossible for me to harm my country by my acts, or better said by my promises, even supposing I had been willing. If by my promises I did not save my unfortunate companions from their chains as I so ardently desired, having obtained my first desire, that they be considered prisoners of war, I saved their lives. Such was at least my idea of the alternative, characteristic of all games of chance, either to leave the promise to the discretion of those who accepted it, or to see if a promise so highly offensive in our case as the recognition of Texas would be fulfilled. The respect for private property and its restitution to the owners that I promised was not only useless but very different from the complete indemnification demanded. sdct In brief, I offered nothing in the name of the nation. In my own name I pledged myself to acts that our government could nullify and I received in exchange the promise of being set free without delay. Where is the treason? Where the pusillanimous cowardice I have been thought guilty of? My voice has always been raised in support of the rights of my country and of my own honor and it is not necessary for me to give a detailed account to make it evident that a prisoner over whose head the sword of vengeance was suspended constantly could not, witho6t putting aside all fear, have withstood the threat of the sword for twenty-two days and have flatly refused at the end of this time to subscribe to the most essential demands that formed the base of the pretensions for the clemency of his conquerors. Such are, however, the stability of the government of Texas, its moral strength and its principles of righteousness that it feared to exercise them in public. It feared that the soldiers might destroy its work, overthrowing its power and, perhaps, making an attempt against those who claimed to be its depositories. For this reason it was necessary to stipulate the terms of my release in a secret treaty, as a result of this fear. Frequently such secret agreements hide great evils; and, the public being disposed to judge as fearful, terrible and astonishing that which is hidden from sight, it has been thought that in my case the mysterious agreement could hide only treason. In truth, that crime committed by a man whom his country has favored so lavishly, who has labored so faithfully for its glory, whose name is met at every turn in the history of M�xico, where it is mentioned with honor even by those who oppose him, would have been a great crime, terrible and unimaginable. However, this secret hid nothing, of which I might be ashamed under the circumstances; but fatality had written that from the very failings of my enemies calumny should draw the venom with which to poison its arrows. I should not have wasted so much time analyzing those agreements for I do not owe my liberty to them. It is true that their terms were partially put into effect, and as a result I was placed on board the Invincible on the first of June, but one hundred and thirty volunteers that arrived from New Orleans made the so-called nation break its pledge. One hundred and thirty volunteers demanded my death, and the government of Texas, whose troops were not attacked on the twenty-first of April because of fear on the part of three thousand men was obliged to give way before the ferocious and tumultuous petition of one hundred and thirty recruits from New Orleans. The moment that I was taken off the vessel and delivered into the hands of the military I asked pleadingly for my death, and at that same instant any obligation on my part entailed by the condition of my immediate release was broken also, and could not have been otherwise. The subsequent acts of the Texans only served to confirm me in this opinion, universally recognized by the common law of peoples. I endured exposure to the cowardly insults. and affronts of the soldier-like mob; I endured the closest confinement; I endured the severe vigilance of those who were most enraged against me, the prisoners that had escaped from Goliad; I endured a succession of attempts to assassinate me; I suffered them to place a heavy ball and chain upon me; and, lastly, on the 30th of June, I suffered them to order me to march to Goliad to be executed in the place when via and his men had died. [In his Diario, Santa Anna says nothing of the order for his execution or march to Goliad. He merely states that on Houston's return he was notified by him that he was free on condition that he pay a visit to General Jackson. Genaro Garc�a, Documentos, II, 40] I saw death approaching without regret. The only regret that I felt in addition to the sorrow of leaving my wife and my children was the thought that M�xico was not happy. Notwithstanding, life was offered to me; and, convinced that its sacrifice on the scaffold would not benefit my country, I listened to the generous advice of the colonist, Stephen F. Austin, whom I had favored in M�xico, and who, more grateful, on seeing me a prisoner and at the point of death, remembered in Texas favors infinitely smaller than those that had been, forgotten entirely in the capital, and decided to save me. The only, means of saving myself in his opinion (and my opinion could not be contrary to his under the circumstances) was to invoke the name of the President of the United States, Andrew Jackson.sdct His character, the conviction in which we have all lived and which was confirmed more than ever, that the Texas War was but a result of his policy, or at least, of his tolerance in sympathy with the wishes of many of his citizens---an opinion that without disguise the Texans themselves expressed; and lastly, the force that a favor so marked as that which Austin proposed to me carries with it, determined me to write a letter to that gentleman on the fourth of July in the terms advised by Austin. In it I flattered the favorite pretension of the Texans without risking anything positively, stating that I was desirous of seeing the war ended and of seeing Texas enter its claims to be a nation through peaceful channels and negotiations. I flattered those distinguished gentleman whom I addressed by hinting the possibility of this outcome if M�xico and the United States cooperated mutually towards that end. The only question which I formally stated in my letter was that he secure my liberty through his influence arid by virtue of the now annulled agreement of the fourteenth of May which I again offered to renew. A copy of this letter was delivered to our minister, Senor Gorostiza, by that government. This letter was published in the newspapers of the North; from one of which it was very poorly translated and printed in those of M�xico as the most shining proof of my treason. The Texas revolutionists whom I fought, the revolutionists of M�xico, who have defamed me, and the speculators of the North together with their sympathizers, all voice this opinion, a singular coincidence of which I cannot be ashamed. In spite of the loud protestations of my enemies, the judicious majority of my fellow-citizens will see in that document the results of an unavoidable necessity at the time it was written. They will see that the generalizations that appear favorable to the Texans do not exceed the bounds necessary to avoid the issue, proposing a peaceful solution as possible but nothing more. They will be convinced that on the way to the scaffold it was not prudent to display a vain boastfulness against those who had raised it; and they will agree, in short, that t could not have used any other language to ask a personal favor of General Jackson. The terms in which he conceived his reply at the same time that they confirm how correct I was in addressing myself to that official prove that the general statements were erroneously taken for explicit demands, for, instead of acceding to the request to interpose his influence in behalf of my liberty-the only definite, clear and unmistakable object of my letter as I explained it he replies by reminding me of my position, which I could not have ignored, refusing as an inevitable consideration in view o the circumstances, his interference in the affairs of Texas in the name of the United States: I do not know how such a pretension could be inferred from the statements in my letter. Thus, General Jackson, having erroneously understood my petition, has replied under a false assumption which my enemies have not stopped to examine but rather following in the same error as the President of the United States, they have made use of these statements as the basis for my denunciation. A misfortune reduced me to the position of a prisoner in in Texas; and this notorious fact should, in the light of sane criticism, make valueless whatever statements I may have made as to the freedom under which I celebrated the agreement of the 4th of May or as to my conviction of the futility of continuing the war, a conviction that cannot be arrived at correctly while in chains. If the idea of the discouragement of the army during the first moments following the 21st of April forced me to agree to an armistice, subsequent events led me to believe that because of other obstacles, independent of the well-known valor of our soldiers, the war would not be renewed for some time. When speaking among foreigners of our resources and enthusiasm, I shall always believe it more decorous to declare myself convinced that it is not expedient to make use of our resources nor to allow our enthusiasm to have free play than to risk the slightest doubt as .to the existence of the former, since that of the latter can never be doubted I believe that the language I adopted on that occasion was the only one that could accomplish my object without dishonor to the nation. And what advantage could have resulted from my expressing a desire that the war should continue, or even from my assertion that it would, when the army, without which it is impossible to wage war, had just undertaken a retreat? It was precisely because the hope of being able to continue the war at the time seemed to me so remote that I was obliged to adopt, as the only course left to me to secure my liberty, the declaration that I was convinced of the advisability of terminating the question peaceably by means of a treaty. Whatever might have been the true cause of the retreat of the expeditionary army as far as Matamoros, the Texans saw, in spite of their ill-dispelled fear after the recent victory, a possibility of such a conclusion, an idea that I thought I could take advantage of to put an end to my sufferings by merely flattering their hopes. I acceded, therefore, to the idea of a treaty, not to be celebrated by me but by the nation; and that is what was stipulated in the agreement of the fourteenth of May which I assured the President, General Jackson, in my letter I was ready to fulfill. The imminent evils I stated in that letter that I wished to avoid were not those of war, for in spite of the false report of the advance of our troops under the command of General Urrea, I did not believe it would take place soon. Although I spoke of deep concern for an early settlement, I took care not to allow myself to be more explicit than to offer that I would try to secure a hearing for the Texans before the government of our country, as stipulated in the agreement, which is as far as my duty went. I stated that if the friendship between M�xico and the United States was enhanced, if both nations became interested (and that alone and not the free President of one and the imprisoned General of the other could do it) in giving stability and protection to Texas, it was evident that it would have to be as an act of their free will. The moment I tried to get a hearing for the commissioners of Texas, whether they were received or not, my only pledge would cease. It is essential, therefore, to fix our attention closely on the fact that the celebration of the treaties that would give Texas being and stability could only be, and was, presented by me as a possibility, and not as a certainty, this being the most compromising point which can be cited against my letter, and even this possibility, I said, could only be the outcome of a national move prompted by humanitarian sympathy for the prisoners who were on the threshold of the scaffold after our troops retreated, and whose situation would exercise a prodigious influence. In the meanwhile Austin circulated my letter among .the Texans who considered my life valuable as a result of the hopes with which I flattered them; and my march to Goliad was suspended; but the idea already disseminated among them of a possible agreement between M�xico and Texas, which they believed guaranteed by the intervention of their protector, facilitated my freedom which I secured later without, however, being bound either by the agreements of May or the letter of the fourth of July. It has been shown how the agreements were annulled and 1tlit reply given by General Jackson to my letter while it imputes to me ideas that I have not entertained, much less expressed, is for me a weapon of defense all the more powerful as it is the same with which I have been attacked. It was written on the fourth of September and it is evident that the President of the United States believes that the principal object of my letter is to put an end to the disasters of civil war in Texas and to ask the intervention of the United States for that purpose. He believes that the agreements signed on the fourteenth of May were negotiated by me as a representative of M�xico and that I asked for the intervention of his country to uphold them. It is only necessary to read my letter in order to realize that it is a private letter in which I express my wishes of seeing the struggle terminated by peaceful negotiations but without reaching the ridiculous extreme of establishing such negotiations, leaving them to the nation. It is seen that my letter is addressed to an honorable man, beloved by the Texans, and very influential because of the position he occupied, to ask him to use his influence to secure my liberty, but not in an official capacity; that there is not a single word in it that suggests the intervention of the United States either for that purpose or in order to put an. end to the war; and that it is nowhere asserted that in the agreements concluded I acted as a representative of M�xico, or that in order to fulfill them I rested the intervention of the Union or, anything of the kind. In short, I shall always repeat that I asked only for the interposition of his personal influence in behalf of my liberty. I cannot allow myself; however, to fail to show how unjustly a part of the hostility which the cabinet in Washington feels for our nation is attributed to me. It is a known fact that the diplomatic correspondence had assumed a very marked character of hatred and hard feelings. The conduct of some of the officials of the United States with regard to Texas was far from being as Ioyal and disinterested as might have been expected of the functionaries of a nation attached to ours by good faith and sincerity. As early as the 20th of June last, the Mexican minister was advised, through the Secretary of State, that, if a very long, and unjust list of claims was not satisfied within a very limited period of time, he would return with the passports of his legation. Consideration was already being given to the alarming message of February last that took me so completely by surprise, since, in passing through the capital, I had just learned of that of December in which, by virtue of the report of the commission sent to Texas, and because of very pertinent considerations for the harmony and good faith due M�xico, the President did not hesitate to express his opinion against the recognition of Texas and to give the greatest assurance of a peaceful and friendly disposition towards my country. Why then turn to me in order to look for and determine the cause of a break between M�xico and the United States? Is it not true; national pride being hurt by the duplicity and the interested motives displayed by that cabinet in favor of the Texan rebels, that there has sprung up in the heart of every Mexican a noble resentment against the bad faith with which we have been treated? sdct Can it be doubted, after reading the communications published by our worthy minister, Senor Gorostiza, that to that fatal policy and that alone, without my connivance or concurrence, the hostile threat is due? I have been fortunate amidst so many troubles in that the claim decreed by the Congress of the United States as a result of that alarming message, and which is soon to be presented is evoked by the diplomatic correspondence of M�xico, proving beyond a doubt that the war with which we are threatened has not been a machination of mine, and that, without my trip to Washington, everything that has happened would have happened. At any rate, the end of my public career has arrived. If it is extremely painful to me that it has not been crowned by glory, if in its stead my military fame and all that can be pleasing and dear to a Mexican has been torn to shreds, if instead of a feeling of pity which the misfortunes of a prisoner well deserve, few of my enemies have failed to make fun of me to the extent of printing in the capital the writings of a Mirabeau Lamar and to speak of my death as event worthy of national rejoicing, I have the consolation that my conscience affords me, assuring me that these misfortunes have not been deserved. If he who reads this writing with impartial attention, convinced of my innocence, does not consider me unworthy of being called, a Mexican, I shall then be happy in my peaceful retreat. Herein is centered all my hope. A constitution has just been published; its ratification during my imprisonment has proved that the abolition of the old system was not the work of my influence. As I voluntarily take a pledge to the new law I elevate to Heaven my most sincere desire for national happiness under its rule. Peace, that precious gift of Heaven, superior to the dreams of optimism and the barbarous pleasure of vengeance, must be dearly appreciated and closely guarded by us as without it [there is no happiness possible]. [A phrase is missing at this point in the text of the first copy printed in Veracruz and also in the on published by Genaro Garcia. This omission makes the last sentence meaningless--C.C.] Let me perish before the fatal day arrives in which the enemies of public order may gather the bitter disappointment of the realization that M�xico cannot be happy except in peace. I am second to none in my desire for the welfare of my country. No one, I believe, can with greater justice claim to have been offended and insulted than I. I could have returned to the honorable position that was wrested from me, for even the most merciless of my enemies have turned their eyes towards me. Their vengeance against a defenseless man would be easy. The least disturbance, however, would be contrary to my invariable determination to preserve peace and, therefore, I have sacrificed everything: complaints, power, influence, all for her sake. My voice has been a continuous echo of my heart, exhorting, my friends and my enemies to be reconciled. This is the only service, I believe, that I can now render my country. Time alone can tell its true worth. In the meantime, without forgetting that my duty is to fly to the national ranks whenever the nation is unfortunately attacked, I do not fear in this refuge either that my fellow-citizens will be unjust or that in recording the Texas campaign history will make my country and my descendants ashamed of my actions.

MANGA DE CLAVO, May 10, 1837 SONS OF DEWITT

COLONY TEXAS |

If, then, everything was favorable, if everything had been

foreseen, and the operations well conducted, what was the cause of the fateful defeat of

San Jacinto? It was the excessive number of raw recruits in the five hundred men under the

command of General C�s. As is well known, such recruits contribute little, in sustaining

a battle, but cause the very grave evil of introducing disorder with their irregular

operations among tried veterans, especially in a surprise. A cargo of supplies I had

ordered not to be brought, and the guarding of which reduced the five hundred men that I

asked for to a bare hundred was also a cause. The capture of an order that was sent to me

from Thompson's as well as that of the officer bringing it, was likewise a cause. [The

disobedient Filisola had sent one of his aides with correspondence from M�xico, who,

before reaching my camp was intercepted, submitted to torture, and made to declare

everything he knew." Genaro Garc�a, Documentos, II, 38--C.C.] The fatigue and

lack of food of the five hundred men of General C�s and of my escort, an imperious

necessity that made me allow them time for their rations, was no less a cause. The disdain

with which a constantly fleeing enemy was generally viewed by our troops, well deserved up

to this time though carried to an extreme, was another cause. The very inaccessibility of

the ground we occupied was itself a cause, for without a close vigilance such as I had

emphatically ordered, it permitted the enemy to occupy successfully the woods to the

right, as it did in an act of desperation. None of these causes was the result of neglect

on my part or of acts immediately emanting from me. I, therefore, can only be held

responsible for having a sickly and weak body, on account of which, after having spent the

previous day marching; the night watching, and the entire morning on horseback, I yielded

to a repose that unfortunately the time allowed the troops brought up by General C�s made

possible and which in moments of greater danger, however, I would not have indulged in. ["He

was of a robust nature" says Col. Manuel Mar�a Gim�nez, an aide and intimate friend

of Santa Anna in his Vida Militar, Genaro Garc�a, Documentos, XXXIV--C.C.sdct]

As general-in-chief I fulfilled my duty by issuing the necessary orders for the

vigilance of our camp, as a man I succumbed to an imperious necessity of nature for which

I do not believe that a charge can be justly brought against any general, much less if

such a rest is taken at the middle of the day, under a tree, and in the very camp itself.

This proves also that I did not abandon myself immoderately to the comforts and pleasant

well-being that our human condition requires, a failing which the greatest men of our age,

including the military men of our century, have not been able to escape, without being

accused of carelessness or lack of foresight.sdct

If, then, everything was favorable, if everything had been

foreseen, and the operations well conducted, what was the cause of the fateful defeat of

San Jacinto? It was the excessive number of raw recruits in the five hundred men under the

command of General C�s. As is well known, such recruits contribute little, in sustaining

a battle, but cause the very grave evil of introducing disorder with their irregular

operations among tried veterans, especially in a surprise. A cargo of supplies I had

ordered not to be brought, and the guarding of which reduced the five hundred men that I

asked for to a bare hundred was also a cause. The capture of an order that was sent to me

from Thompson's as well as that of the officer bringing it, was likewise a cause. [The

disobedient Filisola had sent one of his aides with correspondence from M�xico, who,

before reaching my camp was intercepted, submitted to torture, and made to declare

everything he knew." Genaro Garc�a, Documentos, II, 38--C.C.] The fatigue and

lack of food of the five hundred men of General C�s and of my escort, an imperious

necessity that made me allow them time for their rations, was no less a cause. The disdain

with which a constantly fleeing enemy was generally viewed by our troops, well deserved up

to this time though carried to an extreme, was another cause. The very inaccessibility of

the ground we occupied was itself a cause, for without a close vigilance such as I had

emphatically ordered, it permitted the enemy to occupy successfully the woods to the

right, as it did in an act of desperation. None of these causes was the result of neglect

on my part or of acts immediately emanting from me. I, therefore, can only be held

responsible for having a sickly and weak body, on account of which, after having spent the

previous day marching; the night watching, and the entire morning on horseback, I yielded

to a repose that unfortunately the time allowed the troops brought up by General C�s made

possible and which in moments of greater danger, however, I would not have indulged in. ["He

was of a robust nature" says Col. Manuel Mar�a Gim�nez, an aide and intimate friend

of Santa Anna in his Vida Militar, Genaro Garc�a, Documentos, XXXIV--C.C.sdct]

As general-in-chief I fulfilled my duty by issuing the necessary orders for the

vigilance of our camp, as a man I succumbed to an imperious necessity of nature for which

I do not believe that a charge can be justly brought against any general, much less if

such a rest is taken at the middle of the day, under a tree, and in the very camp itself.

This proves also that I did not abandon myself immoderately to the comforts and pleasant

well-being that our human condition requires, a failing which the greatest men of our age,

including the military men of our century, have not been able to escape, without being

accused of carelessness or lack of foresight.sdct