SONS

OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS For more biographical information, Search Handbook of Texas Online From The Empresario by A.B.J. Hammett, 1973 Confiscation of Property. After San Jacinto, Anglo-American Volunteers from the United States took over the lands, homes and livestock in payment for their armed services. They were quick to file on the most desirable tracts in the Goliad, Victoria, and Refugio area. Overnight the country changed from the Spanish Culture to that of the Anglo-Americans. In 1833, after the death of Don Martín De León, Madam De León resigned herself to spending the remaining years of her life in the colony, where she and her husband had spent so many happy years and she planned to devote her time to the colonists and the church. Her lands and property were also confiscated and she too died in poverty. Outcasts in a Native Land. When Texas began its struggle to gain independence from Mexico, Madam De León and her children sided with the Texans against the Mexicans. Her sons and family fought in the Texas Army. The entire family was loyal and gave liberally of their wealth and treasure to help achieve the Independence of Texas. After the Battle of San Jacinto, almost immediately Victoria was completely changed from a quiet Mexican town to a wild Anglo-American town, dominated by an army and many newcomers that distrusted and hated the Mexicans. The people of Don Martín De León's Colony were advocates of the Constitution of 1824, and were by no means friendly toward Santa Anna, since he revealed his ambitions and designs through his many lawless acts. During the War, when the Mexican Army had remained in Victoria, Don Fernando De León, the eldest son had been forced by the Mexican officers to point out corn, beeves, horses and other property that was required by the army. At another time at gunpoint, he was forced by a Mexican officer to lead the way to a place where the Mexicans seized their goods they required for the invading army. Because of this, which in no way reflected upon their loyalty and what they were doing for the Texans, they were in turn hated and distrusted by many of the new citizens. This entire family then became victims of the warring and hostile forces. Victoria, their home that they had established, was a place no longer safe for them to remain. With a heavy heart, Madam De León under the protection of her son-in-law, Placido Benavides and his family, left the Republic of Texas for Louisiana. Placido Benavides died at Opeloosas, Louisiana. Accompanied by the Carvajal family they proceeded to New Orleans, where for three years they all lived in abject poverty. The only money that this proud and aristocratic family was able to earn was by doing fine sewing and other manual labor. The family decided that it was best to return to Mexico, and after enduring great hardships they finally arrived in Soto la Marina, the community and childhood home of Madam De León. Their dream of returning home was immediately shattered. Everything was changed. It was no longer home and shortly after their arrival in Soto la Marina, Augustina De León Benavides, died, just five years after her husband's death. With the untenable situation existing for this family in their native land of Mexico, Madam De León longed to return to her Texas. Finally in 1844, accompanied by her grandchildren of the Benavides family, she was able to return to Texas, and to Victoria. It was indeed a sad homecoming for Madam De León, as all of the tremendous herds of horses, cattle and mules were gone. Most all of the property, their homes, furnishings and other accessories had been seized by the newcomers for one reason or another, but still it was the place she longed to be. She continued to devote much of her time to the Church, where in better days, she and her husband, Don Martín De León, had given the valuable golden altar vessels. Her life was now entirely different with her vast herds of cattle, horses and property in the hands of thieves and some honest people, who thought the cattle and horses were really wild herds, regardless of the De León brand. Her children and other relatives had all been ostracized from the land of their adoption and birth, because of their supposed Mexican sympathy. This of course, was not true. Five years after Doña Patricia De León returned to her native Victoria, she died in 1849. At the time of her death, it was indeed a much different place than the years spent with her husband in the happy, prosperous colony which she and her children had carved out of a wilderness. A Lamentable Tragedy. In the year of 1936, the State of Texas finally erected a monument in memory of Don Martín De León, in the Evergreen Cemetery, in Victoria, Texas. In 1883, Victor Rose, author of the History of Victoria had some very choice words to say, commenting on the sad end to the noble family of Don Martín De León. About this aristocratic family of royal Spanish blood, the richest people in Texas, and loyal supporters of the cause of Texas, Rose said:

Another historian well acquainted with the early history of Victoria and the De León family, reports, that at the time the Catholic Church (1853) reinterred the bodies of this family to one common grave in Evergreen Cemetery. The family had been so robbed and persecuted, that they were financially unable to erect a tombstone. And so it was, until the State of Texas, over one hundred and twelve years later, erected a monument in Evergreen Cemetery to the memory of Don Martín De León. One hundred and forty-seven years, since the founding of this colony there is no suitable monument in the cemetery marking the graves of Don Martín De León's loyal family, his faithful wife, Doña Patricia, who contributed and did much for the cause of Texas, the Church and the community, or his sons, who were important commissioners and administrators in the affairs of the colony, and loyal to the cause of Texas, with their money, possessions, and their lives. According to historical records, the remains of this family were removed from their individual graves in their Catholic church yard cemetery, and the remains of Don Martín De León, his wife, Doña Patricia and his four sons, Don Fernando, Don Felix, Don Silvestre and Don Agapito were all buried together in the same grave in Evergreen Cemetery. A small inconspicuous and illegible, limestone marker in the corner of the Cemetery Plot was placed there when Don Fernando died in 1853. No monuments were erected for Doña Patricia, Don Felix, Don Silvestre, or Agapito, and in over one hundred eighteen years there has never been an appropriate, commemorative monument for the Empresario's first son and Commissioner of the Colony, Don Fernando De León. What an end, and what a loss of unpublished historical facts, in connection with the early history of Texas, lies in the "inconspicuous" grave of Doña Patricia de la Garza De León, loyal wife of the Empresario and their sons, Don Fernando, Don Felix, Don Silvestre, and Don Agapito. Memorial Markers and Tribute to the De León Family In 1971 the Don Martín De León Memorial Foundation was established and funds were raised and permission granted to establish State Historical Markers and a preserved site in the cemetery to honor members of the De León family and their contribution to Texas. Markers were established for Empresario Martín De León, wife Patricia De León, and sons Fernando, Silvestre, Felix and Agapito. On 8 April 1972 dedication services were held at Victoria City Hall and Evergreen Cemetery. It was attended by several hundred including dignataries from Texas, the United States and Mexico. Present was the great grandson of first President of Mexico Guadalupe Victoria after which the city was named. This section of Sons of DeWitt Colony of Texas on the De León Colony of Texas is dedicated to author A.B.J. Hammett whose efforts were instrumental in bringing recognition to the neglected history of the De León Colony and the family of Empresario Don Martín De León--Don Guillermo

From The Handbook of Texas. As a career officer stationed at Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio (La Bahía), Manchola served as comandante in 1826-27 and again in 1831. As such he aided his father-in-law in forcing the inhabitants of DeWitt's Old Station out of De León's territory into Gonzales in 1827. As De León's attorney, Manchola petitioned the Mexican government on April 13, 1829, to augment the boundaries of his father-in-law's colony to accommodate an additional 150 families. Although this was granted, De León failed to gain title to the barrier islands for which Power and Hewetson held the original claim. In the fall of 1828 the District Electoral Assembly of Texas elected Manchola and José María Balmasceda deputies to the Coahuila and Texas state legislature. Manchola wrote Stephen F. Austin in October asking his suggestions for the welfare of Texas. Manchola helped establish the municipality of Guadalupe Victoria during the 1829 session and declared his support of separate statehood for Texas and Coahuila. Early in February 1829 he protested to Governor Agustín Viesca against the failure of the Mexican government to carry out the order of September 1823 secularizing all missions that had been in operation for at least ten years. He prepared a history of the missions of his district to demonstrate that they had been in operation more than ten years, recalled the grievances of settlers against the mission Indians, and criticized Father José Antonio Díaz de León's efforts to obstruct the secularization process. Manchola then demanded the immediate transfer of the missions and the sale of their lands to settlers. Finally he petitioned to change the "meaningless name" of La Bahía to Goliad, "which is an anagram made from the surname [Hidalgo] of the heroic giant of our revolution". In response, the government issued Decree Number 73 of February 4, 1829, which granted La Bahía the title of Villa de Goliad, thereby elevating the presidio to a town. By March 6 Governor Viesca had ordered the political chief at Bexar to carry out the secularization order of 1823; it was not implemented until February 1830. Manchola was reelected to the state legislature in 1830 and received a vote of confidence from the ayuntamiento of San Felipe. Manchola supported the Constitution of 1824 and continued to advocate separate statehood for Texas and Coahuila. As the Goliad delegate to the Convention of 1832 he volunteered to accompany William H. Wharton to Mexico City to present the convention's petitions for separation of Coahuila from Texas. Stephen F. Austin convinced them that the proceedings were untimely, however, and the mission was cancelled. Manchola probably died a few weeks later in the cholera epidemic of 1832-33. His widow became one of the large landowners of the region. She was issued two grants of two leagues each on Coleto Creek as a De León colonist and two two-league tracts on the San Antonio River bordering Villa de Goliad in 1833, as well as additional grants in 1834 as a Power and Hewetson colonist on lands that the De Leóns had owned earlier. She apparently died in Texas. The De Leóns fell victim to the reaction against Texans of Mexican descent after the Texas Revolution and were forced to abandon their lands and flee to Mexico. Captain Placido Benavides

Several times previous to this campaign Captain Benavides and Silvestre De León had led expeditions against the hostile Indians; following them to their villages and punishing them for depredations committed. At one time they pursued the Tonkawas to their retreat on the peninsula, and brought back with them some eighteen Tonkawa children, which were distributed among the citizen, and baptized. Early in 1836, while engaged with others on the Nueces, in procuring horses for the Texan cavalry, Capt. Benavides met with a hazardous adventure, in being surprised and closely pursued by the dragoons of Gen. Urrea. He and Dr. Grant were riding in advance of the caballado, and upon the sudden appearance of the cavalry in their front, put spurs to their horses; and after an exciting chase Dr. Grant was killed, Benavides effecting his escape. Says Mr. Patricio De León, "Captain Placido Benavides often stated that had Dr. Grant acted in conformity to his suggestions he unquestionably would have succeeded in effecting his escape, as he did. But the Doctor became excited and beat his horse, and used his spurs with unnecessary severity, which, confusing the animal retarded instead of accelerating his speed. Placido Benavides retired, with the De León family to New Orleans after the battle of San Jacinto, and died a Opeloosas, in the parish of San Landry, in 1837. His widow accompanied Mrs. Carbajal to Mexico in 1839, and lived in the town of Sota la Marina, where she died five years after the death of her husband. Their family consisted of three daughters: Doña Pilar, the eldest married Don Cristobal Garza, who lived at Rio Grande City, Texas; Doña Librada, the second daughter is the wife of Mr. Patricio De León, a prominent and much respected citizen of the Mission Valley neighborhood. Doña Martianita, the youngest, married Don Serapio Garza, of Rio Grande City. The brothers of Capt. Benavides were Ysidro, Eugenio, and Nicolas. They returned from Louisiana in 1838, and settled upon their lands. Don Ysidro on the Chocolate creek, in Calhoun county, Don Nicolas on the Arenosos, and Eugenio, on the Placido creek, as stated. Don Ysidro married Miss Cayetana Moreno, and had three sons, viz: J. M. Benavides, who married Miss Josépha Benavides, and now resides on the Placido creek, Victoria county; Placido, second son, married Miss Romualda Hinojosa, of Mier, Mexico, at the present writing, a resident of Duval county, Texas, at the Benavides station on the railroad leading from Corpus Christi to Laredo; and Ysidro Jr. who married Miss Reyes Garza, of Goliad, and resides in Duval county; and three daughters, the eldest of whom, Miss Juanita, married Capt. James Cummings; the second, María Antonia, married the Rev. W. M. Sheely, a Methodist preacher; and Martianita, the youngest, married Mr. Warren Sheely. Don Eugenio Benavides had four sons, viz: David, Ygnacio, Francisco, deceased, and Romulo, who married Miss Refugia Lopez, and resides on the Placido creek, in Victoria county; and four daughters: Josépha, Pilar, and Librada, all deceased, and Leónor, widow of Ines Villarreal, who lives on the Placido, in Victoria county, her husband having died May 10th, 1882.

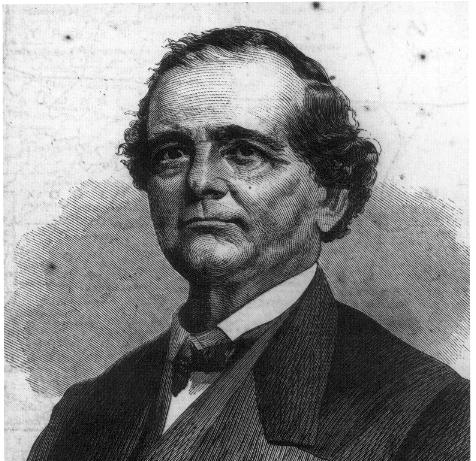

The massacre of the friends of Don Ysidro Benavides, briefly adverted to in the narrative proper, was one of the most heinous crimes ever perpetrated by people claiming to be civilized. This occurred in Zarco creek, nine miles west of Goliad in 1843; the victims were nine in number, only the names of José M. Barrera and his brother, Manuel Barrera, and Don Regalado Moreno, brother of Don Ysidro's wife, being now remembered. They had been on a visit to the family of the latter, and were returning home, in Mier, Mexico, with a small quantity of tobacco and other goods for the Mexican trade. They were pursued by a party of "cowboys," led by "Mustang" Grey; overtaken, disarmed through professions of friendship, and executed in a ghastly heap; the paltry spoil furnished the sole motive for this act of supreme atrocity. Strange to relate that though the thugs fired upon their victims from the very muzzle of their guns, one of the number, José M. Barrera, was not killed, though grievously wounded in the face. Mr. John Fagan, some time after found him wandering about in the vicinity of Carlos Ranch, and had him conveyed to the home of Don Ysidro Benavides, on the Chocolate Creek. When able to travel, Mr. Benavides conveyed him to Mier, where he died of the effects of the wound two years afterward. Not the least strange is the statement that the perpetrators not only were never made to suffer the penalty of their crime, but no steps, that we have any knowledge of, were ever taken to bring them to the bar of justice. In the light of which, and kindred facts, it is not strange that Texas achieved a most unsavory reputation among the more moral and law abiding citizens of the older states, and we of the present day have more cause to rejoice that the desperado, robber and murderer has gone, than that the savage Comanche has sounded his war whoop long since for the last time in the beautiful valley of our own Guadalupe. [The photo is from Hammett's The Empresario and noted in error in that and several sources as Placido Benavides. According to researcher Jose Guerro Jr., the photo is actually Santos Benavides of Laredo. Second greatgrandson of the founder of Laredo and a major influence in border politics in Laredo in the second half of the 19th century, Benavides was a member of the Texas Legislature. As Colonel in the army of the Confederate States of America, Benavides was the highest ranking Mexican-American to serve the Confederacy, one of two brothers that influenced late 19th century Laredo politics and served in the Confederate Army. It is unknown if he was related to Placido Benavides.] General José María Jesús

Carabajal An article entitled "The Carvajal Disturbances" in the October, 1951, Quarterly caused the writer to review notes accumulated through the years having to do with the picturesque and human story of José María Carbajal, the San Antonio lad who was educated by Alexander Campbell and who eventually became General of Division in the Mexican army and Benito Juárez confidential agent to money lenders of the United States. The writer had supposed that José María was a son of Nicolás Carabajal, who was granted land in the Refugio area by the ayuntamiento of Goliad before the General Colonization Law of Coahuila and Texas was in effect. This was a mistake. Nicolás Carabajal could not have been the father of José María, who was a lad of twelve or thirteen years, living in the family of his widowed mother at San Antonio when he won the friendship of Stephen F. Austin and later of Littleberry Hawkins during the winter of 1822-1823. Records of the Mission Refugio show that Nicolás Carabajal and his wife, Catarina Falcon, were the parents of María Gertrudis Ynes Carbajal, baptized at the Mission of Refugio in 1810 and sponsors of other children baptized at Mission Refugio in 1810 and 1811. But María Catarina Falcon, aged about twenty-seven, died and was buried at this mission in 1812. Mission burial records identify her as the wife of Nicolás Carabajal. Manuela Carabajal, not otherwise identified, was sponsor of an infant baptized at the mission in 1827 [W. H. Oberste, History of Refugio Mission (Refugio, 1942), 386-392]. Since married women usually appear in Spanish church records under their own family names rather than those of their husbands, Manuela was probably a daughter of Nicolás Carbajal rather than his second wife. Dolores Carabajal, widow, applied for land as head of a family in the colony of James Power and James Hewetson in 1834. This was one of the applications left unfinished because of the sudden departure of José Jesús Vidaurri, commissioner to extend titles, in the autumn of 1834. Young José María Carbajal accompanied Littleberry Hawkins to Kentucky on his return from Texas in May, 1823. Hawkins in his letter of October 27, 1824, to Stephen F. Austin interpolated into an account of his own reverses and his brother's death; "Hosa Mureab is well and going to school learning fast." [Eugene C. Barker (ed.), The Austin Papers (Vols. I and II, Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Years 1919 and 1922, Washington, 1924, 1928), 1, 921]. On July 2, 1826, Joséph Ficklin, postmaster at Lexington, Kentucky, wrote to Stephen F. Austin, transmitting a letter in schoolboy English from young José María to his mother, in which he told her that

Postmaster Ficklin adds, in his covering note:

Young Carbajal next appears in the Austin Papers in his own letter to Stephen F. Austin, dated Bethany, Virginia, March 8, 1830, requesting Austin's help in selling Spanish bibles in Texas and asking for a copy of Austin's map. Austin, in a letter dated January 30, 1832, introducing young Carbajal to Mary Austin Holley, explains:

It is clear from Austin's correspondence that young Carbajal returned to Texas shortly after the date of his letter of March 8, 1830, and prior to May 31, 1830, when Austin, then at Bexar, wrote to José Antonio Navarro concerning Navarro's appointment as commissioner for Ben Milam's colony, adding:

Young Carbajal mentioned José A. Navarro as his cousin [primo] in a letter to Austin written on September 1, 1830, from Bexar. Austin's plan to have young Carbajal live in his house while learning the theory and practice of land surveying appears to have been accomplished, since Austin, then at Bexar en route to Saltillo, wrote Samuel May Williams at San Felipe on December 29, 1830: "Let José Carabajal have my odd pistol-all is satisfactorily explained with Navarro." Explanations due Navarro may have had to do with young Carbajal's appointment as surveyor by José Francisco Madero, commissioner to extend titles in the David G. Burnett and Joseph Vehlein colonies. Madero arrived at San Felipe on January 14, 1831, and shortly thereafter began his work as commissioner at George Orr's on the Trinity River. He and Carbajal were both arrested by John Davis Bradburn, commandant at Anahuac, on February 13, 1831. They were soon released. Madero discontinued extending titles to American colonists; Carbajal, however, appears to have been profitably employed surveying grants extended to Mexican citizens in this area throughout the year 1831. Nathaniel Cox, Austin's New Orleans friend, who in 1826 had transmitted Ficklin's letter concerning young Carbajal, wrote Austin from New Orleans on March 22, 1832:

Carbajal wrote Austin from Bexar on June 4, 1832, and assisted Austin at Bexar in translating the memorial of the Texas Convention to the Mexican government in May 1833. Just when he transferred his activities to Victoria and married a daughter of empresario Martín de León, the writer does not know, but he was surveyor for De León's colony when title to the five-league Sacramento grant was extended to Martín de León in January, 1833; and was evidently unmarried when he visited New Orleans in 1832. It is certain that he was not appointed surveyor for De León's colony in 1824, as stated in several published histories following Victor M. Rose. Since Rose was a conscientious historian, and careful with his facts, his "1824" was, no doubt, a misprint for "1834." [Victor M. Rose, Same Historical Facts in Regard to the Settlement of Victoria, Texas (Laredo, 1883), 111-112] Letters in the Austin Papers to, from, and concerning Carbajal suggest that he was born about 1810. Refugio de León, whom he married, was born in 1812. The Ficklin letter of 1826 states positively that Luciano Navarro was his brother-in-law, and Carbajal's letter of July 2, 1826, to his mother mentions "brothers and sisters," indicating at least two of each. Manuel Carvajal and Placido Benavides were the assisting witnesses who acted with Commissioner Fernando de León in issuing the Sacramento title to Martín de León in 1833. Henderson Yoakum, in introducing Edward Gritten in connection with war and peace measures of the summer of 1835, remarks that

Yoakum wrote during the period in the early 1850's when José María Carbajal was much in the public eye and when the title "colonel" would not have applied to anyone else of the Carbajal name. [A letter from W.B. Travis from San Felipe to provisional governor Henry Smith in Columbia of June 1835 refers to "A decree, authorizing Jose Maria Carvajal to publish all the decrees of the State Congress since the adoption of the Constitution in English and Spanish, and to have the exclusive privilege of selling them, for six years at $2.50 per vol of 200 pages This Digest when published will be authentic and will have the same force as such works do in the N. States---"--WLM] "On the Island of Galveston, Texas," on April 15, 1836, six days before the battle of San Jacinto, Philip Dimitt certified:

John H. Lewis attested that he knew Dimitt's statements to be correct, and Benjamin H. Holland and William Brenan, who escaped from the firing squads at Goliad, and Captain Jack Shackelford, who was spared, added that "This is to certify that the above mentioned Carbajal served with Colonel Fannin, and gallantly fought at the battle of Coleto, and was afterward inhumanely and traitorously butchered at Goliad." On the basis of these certificates, Edward Gritten, on August 12, 1836, collected Mariano Carabajal's pay, as administrator and legal representative of Mariano's heirs.

Victor M. Rose has preserved most of the details which have come down to present-day historians concerning life in De León's colony and activities of its members during the troubles of 1835-1836. Concerning José María J. Carbajal's capture aboard the Hannah Elizabeth in November, 1835, subsequent detention at Brazos de Santiago and Matamoros, and eventual escape, Rose adds that after the escape of his brother-in-law, Fernando de León from Brazos de Santiago,

From Rose's sketch of Fernando de León and other sources, it is known that the enforced departure of the De León family was months after the battle of San Jacinto, and that after his capture aboard the Hannah Elizabeth, José María Carbajal positively did not return to Texas "in time to sign the Goliad Declaration of Independence." Concerning the expulsion of the De León family from Victoria, Rose says:

Rose also relates that Captain Placido Benavides retired to New Orleans with the De León family after the battle of San Jacinto and died in Opelousas, Louisiana, in 1837. Two years later his widow, Agustina de León, accompanied Mrs. Carbajal to Mexico and lived in the town of Soto la Marina, where she died about 1842. After the exile and despoliation of the De León family, Carbajal never considered himself a Texan; the reason for his return to Texas from Louisiana in 1839 was to seek Texan help for the Mexican Federals in a new "War of the Federation." His approach to President Mirabeau B. Lamar was through his brother-in-law, Luciano Navarro. [Luciano Navarro, Bexar, August 9, 1839, to President Mirabeau B. Lamar in Lamar Papers, 111, 60, Calendar No. 1395] The story of Carbajal's personal contribution to the Federalist War of 1839-1841 is preserved in the Lamar Papers. He was wounded in October, 1839, in Pavon's battle at Alto del Limpia, near Mier, Tamaulipas. of this battle, Major Richard Roman, soldier of San Jacinto, who commanded a Texan company in this action, affirmed that

Space will not permit following Carbajal through the Mexican War, the war of the Plan de la Loba, the "Cortina War" of 1859-1860, the War of the Rojos and Crinolinos in 1861, and his two man capture of the city of Matamoros in June, 1866. But it is worthy of note that in one of his blasts at the Mexican government in 1876, General Juan N. Cortina stated that he took shelter in the mountains of Burgos in 1860 on the advice of his kinsman, General Carvajal, and that in July 1875, Colonels John L. Haynes and John S. Ford, opposing leaders on the Rio Grande border in 1864-1865, together with a dozen other well-known citizens of Brownsville who knew the facts, said of General Carbajal's contributions to Mexico's defense against the French, 1863-1867:

Reprint from The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. LV, April, 1952, pages 475-483 & Bits of Texas History in the Melting Pot of America, by José Tomas Canales. SONS OF DEWITT

COLONY TEXAS |

Rafael Manchola was a prominent

young man from an aristocratic Spanish family. He possessed a good education and was very

ambitious. Rafael became a part of the important De León family when he married the third

daughter of Don Martín De León, María de Jesús De León. The marriage was one of the

big social events of the colony and like the others, with gaiety, dancing and a

celebration lasting many days. To this couple, a daughter, Francisca was born. Francisca,

a well educated young lady married Crisoval Morales. It has been recorded that Rafael

Manchola, a resident of La Bahia and an elected deputy to the State Legislature of

Coahuila and Texas was the person who petitioned that legislation to change the name of La

Bahia to Goliad. He explained that the name of La Bahia del Espiritu Santo had little

meaning but that the name of Goliad, an anagram composed from the important letters in the

surname (Hidalgo) the heroic giant of the Revolution had great meaning. Accordingly, the

legislature granted La Bahia, the title of Villa de Goliad on February 4,1831. In the year

1831, Rafael Manchola commanded the troo ps at the Presidio La Bahia. He also became the

Alcalde of Goliad. Like the other members of the De León family, Rafael Manchola acquired

large tracts of land and established himself in the cattle business. His famous brand was

one of the first registered in Don Martín De León's capital city of Guadalupe Victoria

in the year 1838.

Rafael Manchola was a prominent

young man from an aristocratic Spanish family. He possessed a good education and was very

ambitious. Rafael became a part of the important De León family when he married the third

daughter of Don Martín De León, María de Jesús De León. The marriage was one of the

big social events of the colony and like the others, with gaiety, dancing and a

celebration lasting many days. To this couple, a daughter, Francisca was born. Francisca,

a well educated young lady married Crisoval Morales. It has been recorded that Rafael

Manchola, a resident of La Bahia and an elected deputy to the State Legislature of

Coahuila and Texas was the person who petitioned that legislation to change the name of La

Bahia to Goliad. He explained that the name of La Bahia del Espiritu Santo had little

meaning but that the name of Goliad, an anagram composed from the important letters in the

surname (Hidalgo) the heroic giant of the Revolution had great meaning. Accordingly, the

legislature granted La Bahia, the title of Villa de Goliad on February 4,1831. In the year

1831, Rafael Manchola commanded the troo ps at the Presidio La Bahia. He also became the

Alcalde of Goliad. Like the other members of the De León family, Rafael Manchola acquired

large tracts of land and established himself in the cattle business. His famous brand was

one of the first registered in Don Martín De León's capital city of Guadalupe Victoria

in the year 1838. Don Placido Benavides

was a native of the village of Reynosa, state of Tamaulipas, Mexico, and when but a mere

child was taken in charge by his Padrino, or God Father, Captain Don Henrique Villarreal,

and properly educated. In the year 1828, he, in company with his older brothers, came to

Don Martín De León's colony; being at that time quite young. He was employed by the

commissioner, Don Fernando, as a secretary in all the business transactions relating to

the issuance of land titles to the colonists, until the year 1831, when he married Miss

Augustina De León, daughter of the Empresario; and at once applied for a league and labor

of land, to which he was entitled, as an actual settler; and located the same on the

Placido creek, in Victoria county, adjoining the land of his brother, Don Eugenio, where

they both established ranches of livestock. The year following he was elected alcalde of

Guadalupe Victoria; and reelected in 1834. About that time, in consequence of the death of

Don Martín, he was authorized by the supreme government to continue the operations

necessary to fulfill his second contract for the introduction of colonists. The next year

he hastened, at the head of his company, to reinforce the Texas army operating against the

forces of General Cos, in

Don Placido Benavides

was a native of the village of Reynosa, state of Tamaulipas, Mexico, and when but a mere

child was taken in charge by his Padrino, or God Father, Captain Don Henrique Villarreal,

and properly educated. In the year 1828, he, in company with his older brothers, came to

Don Martín De León's colony; being at that time quite young. He was employed by the

commissioner, Don Fernando, as a secretary in all the business transactions relating to

the issuance of land titles to the colonists, until the year 1831, when he married Miss

Augustina De León, daughter of the Empresario; and at once applied for a league and labor

of land, to which he was entitled, as an actual settler; and located the same on the

Placido creek, in Victoria county, adjoining the land of his brother, Don Eugenio, where

they both established ranches of livestock. The year following he was elected alcalde of

Guadalupe Victoria; and reelected in 1834. About that time, in consequence of the death of

Don Martín, he was authorized by the supreme government to continue the operations

necessary to fulfill his second contract for the introduction of colonists. The next year

he hastened, at the head of his company, to reinforce the Texas army operating against the

forces of General Cos, in

[Photo

José M. J. Carvajal from Viva Tejas by Ruben Lozano] Fernando de León,

commissioner to issue title to De León's settlers, extended headright grants to two

members of the Carabajal family: one to José Maria J. Carbajal; the other to José Luis

Carbajal. An examination of the original grants in the General Land Office should supply

the identity of José Luis. Another hint as to Carbajal's family connections was

developed at the trial of Lopez v. Garza,, a partition suit in the district court of Starr

County, in June, 1944. The land involved, Porcion No. 84, ancient jurisdiction of Camargo,

had been owned by Julian de la Garza of De León's Colony at the time of his death.

Julian's grandson testified that he was killed by Indians at his rancho on the Nueces

River, below San Patricio, in June, 1836. His second wife, Leónor Benavides, was a sister

of

[Photo

José M. J. Carvajal from Viva Tejas by Ruben Lozano] Fernando de León,

commissioner to issue title to De León's settlers, extended headright grants to two

members of the Carabajal family: one to José Maria J. Carbajal; the other to José Luis

Carbajal. An examination of the original grants in the General Land Office should supply

the identity of José Luis. Another hint as to Carbajal's family connections was

developed at the trial of Lopez v. Garza,, a partition suit in the district court of Starr

County, in June, 1944. The land involved, Porcion No. 84, ancient jurisdiction of Camargo,

had been owned by Julian de la Garza of De León's Colony at the time of his death.

Julian's grandson testified that he was killed by Indians at his rancho on the Nueces

River, below San Patricio, in June, 1836. His second wife, Leónor Benavides, was a sister

of  [Wood engraving from a photograph

appeared in Harper's Weekly, 1866, provided courtesy of Jose Guerra]. Colonel

Ford, who had served under Carbajal in the War of the Plan de la Loba, in 1851, paid this

final tribute to his long-time friend:

[Wood engraving from a photograph

appeared in Harper's Weekly, 1866, provided courtesy of Jose Guerra]. Colonel

Ford, who had served under Carbajal in the War of the Plan de la Loba, in 1851, paid this

final tribute to his long-time friend: