SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

© 1997-2003, Wallace L. McKeehan,

All Rights Reserved

Regulators-Index

Captain Benjamin Merrell &

The Regulators of Colonial North Carolina

Page 2 (Back to page 1)

During the quiet period, then, the Regulator movement seems to have developed a tradition; an esprit de corps; a certain understanding of their potential. This is evidenced by the words of the Anson County petition of 1769, which pushes Regulator grievances further than ever before. The writers complain

That the violation of the Kings Instructions to his delegates, their artfulness in concealing the same from him; and the great Injury the People thereby sustains; is a manifest oppression...

The petition goes on to indict the governor and council for several irregularities in assigning and accounting for land grants, asks that taxes be made payable in produce, and suggests location for tax commodity warehouses in which to store these goods. Several of the locations mentioned are outside Anson County--a strange inclusion, unless there had been previous consultation with other Regulator groups. Further, the petition recommends

That Doctor Benjamin Franklin or some other known patriot be appointed Agent, to represent the unhappy state of this Province to his Majesty, and to solicit the several Boards in England.

Until new documentation is found, the author or authors of the above-mentioned petition remain unknown.

Still, it might be speculated that the fine hand of Herman Husband somehow reached out to Anson County and that, indeed, Husband was the chief agitator of the backcountry. The 1767-1768 legislature had declared Hillsborough a borough town, eligible to elect its own representative to the assembly. On March 12, 1770, the first such election was held, and the man elected was none other than Edmund Fanning. Orange County returned Regulators Herman Husband and John Pryor, both of whom had served in the previous assembly. Thomas Person, a Regulator from Granville County, was also returned to the legislature. During the summer of 1770 the Orange County Regulators drew up a petition to be presented at the fall term of Superior Court, and on September 22, this court convened in Hillsborougb. The only judge on the bench was associate justice Richardson Henderson. To him James Hunter presented the Regulator document. Action on the petition was deferred until the following Monday. The New York Gazette, in an article datelined "New Bern," reported the next series of events.

……on Monday, the second day of the court, a very large number of . . . people, headed by men of considerable property, appeared in Hillsborough, armed with clubs, whips loaded at the ends with lead or iron, and many other offensive weapons, and at once beset the court-house. The first object of their revenge was Mr. John Williams, a gentleman of the law, whom they assaulted as he was entering the court; him they cruelly abused with many and violent blows with their loaded whips on the head, and different Darts of his body, until he by great good fortune made his escape, and took shelter in a neighboring store. They then entered the court-house, and immediately fixed their attention on Col. Fanning, as the next object of their cruelty; he for safety had retired to the Judge's seat. . . from which he might make ... defense... but vain were all his efforts...

They seized him by the heels, dragged him down the steps, his head striking very violently on every step, carried him to the door, and forcing him out, dragged him on the ground. . . till at length. . . he rescued himself. . . and took shelter in a house: the vultures pursued him there. . . they left him for a while, retreated to the court-house, knocked down. . . the deputy clerk of the crown, ascended the bench, shook their whips over Judge Henderson, told him his turn was next, ordered him to pursue business, but in the manner they should describe which was: that no lawyers should enter the court-house, no juries but what they pick, and order new trials in cases where some of them had been cast for their malpractices. They then seized Mr. Hooper, a gentleman of the law dragged and paraded him through the streets, and treated him with every mark of contempt and insult.

This closed the first day. But the second day presented a scene, if possible, more tragic: immediately on their discovering that the judge had made his escape from their fury, and refused to submit. . . they marched in a body to Colonel Fanning's house ... entered the same, destroyed every piece of furniture in it, ripped open his beds, broke and threw in the streets every piece of china and glass-ware in the house, scattered all his papers and books in the winds, seized all his plate, cash, and proclamation money; entered his cellar. . . Being now drunk with rage. . . (and) liquor... they took his wearing clothes, stuck them on a pole, paraded them in triumph through the streets, and to close the scene, pulled down and laid his house in ruins. . .

Other reports tell of the mob smashing windows of private residents, administering other beatings, and generally terrorizing the town. The Regulators also held a mock court session in the courthouse, entering judgments in the court minutes---"In McMund vs. Courtney the comment was 'Damn'd Rogues'; in Wilson vs. Harris, "All Harris's are Rogues;" in Brumfield vs. Ferrel (sic), "Nonsense let them agree for Ferrell (sic) has gone Hellward;" . . . in Fanning vs. Smith, "Fanning pays costs but loses nothing;" . . . Finally, the rioters dispersed. They had numbered about 150 and had been led by William Butler, Rednap Howell, James Hunter, and Herman Husband.

On Friday of that same week, Judge Henderson wrote to Tryon, informing him of this second Hillsborough riot. Shortly afterward, Henderson's house and outbuildings in Granville County were burned by arsonists. Orange County officials were demanding action; rumors were spreading. Orange, Granville, Halifax, Johnston, Anson, Mecklenburg, and Tryon counties now all had Regulators. Tryon met with the council to discuss the Hillsborough activity; the council urged that the militia be called up immediately. Still, there was no widespread panic. On December 5, 1770 the assembly met in New Bern. It was there reported that the Regulators were massing in the backcountry, preparing to march east and attack the assembly itself. Several companies of militia had been assembled and were awaiting this expected attack. Even as matters worsened, the Governor and assembly attempted to deal with the Regulator grievances---whether these actions were "in spite of" or "because of" the Regulators' activity is a questionable point.

Tryon addressed the assembly's first meeting. His speech covered four points: "The Abuses in the Conduct of Public Funds; The General Complaints Against Offices and Officers; The Evil Arising From the Circulation of Counterfeit Money; and the Injuries offered to His Majesty's Government at and since the last Hillsborough Superior Court." The legislature, with Herman Husband in attendance, began consideration of bills to answer the first three points. Apparently, Herman Husband felt that his star was ascending, and acted accordingly. On December 20 the House resolved to expel him from its membership, accusing him of being a "promotor of the late Riots and seditions in the County of Orange and other parts. . .," of lying to a House committee considering the libel question, and of insinuating "that in case he should be confined by order of the House he expected down a number of people to release him." The last charge may have been the real reason for Husband's expulsion. James Iredell, in a letter dated December 21, confided to an absent fellow legislator that "it seems that a majority of the house are of regulating Principles." Given this fact, and in light of the fear the Regulators had engendered, Husband may have seen himself in an advantageous position. He could conceivably assume open leadership of the Regulators by emphasizing to assembly members the Regulators' loyalty to him.

The assemblymen, however, thought Husband's actions of a less noble purpose. They not only stripped the man of his legislative power, but also requested the chief justice to issue a warrant for his arrest on a charge of libeling Maurice Moore. The libel admittedly had only a tenuous connection with Husband. James Hunter had actually written the letter; the charge against Husband was that he had altered the original correspondence and had it published in a New Bern paper. Still, the warrant was issued and Husband was arrested and confined, an action thought necessary because, otherwise, ". . . it may be of fatal consequence to the Country should he be suffered to rejoin the regulators in the back settlements of this Province." During this same period the legislature was also passing a number of "Regulator" bills. Four new counties---Wake, Guilford, Chatham, and Surry---were erected in the backcountry; acts were passed regarding sheriffs' appointments and duties; a table of fees for attorneys was established; militia officers' fees were more strictly regulated; the chief justice was put on a provincial salary; a method to simplify the legal collection of small debts was created. Thus, in a very real sense, the 1770 legislature did much to meet Regulator grievances. But, the government and the Regulators continued on a collision course. The attorney general, Thomas McGuire, had recently informed the governor and council that, legally, the Hillsborough mob could be charged with nothing stronger than "riot"---a misdemeanor. Tryon was searching for a way to halt the Regulator movement, and he and the council had considered charging the Hillsborough rioters with high treason---punishable by death. In his message, McGuire had suggested alternate methods of dealing with the Regulators, and these suggestions had formed the basis for Johnston's riot bill.

As late as December 21, 1770, there was considerable doubt that the riot bill would pass. It was an extreme "law and order" measure designed, its defenders believed, to match the extremity of the Regulators' riotous actions. Meanwhile, however, news of Husband's arrest had reached the Regulators, who began assembling at Cross Creek (Fayetteville) in preparation for a march on New Bern---their purpose being to rescue Herman Husband. This was too much for the assembly. After Christmas recess, on January 15, 1771, the "Johnston Riot Act" was passed. Now, it seemed that both the government and the Regulators had passed the point of retreat. Husband was not rescued by any Regulator band. On Friday, February 8, in Superior Court in New Bern, a jury returned a "no bill" verdict on Husband's alleged libel, and he was freed to meet the Regulators at Cross Creek and return to the backcountry. Otherwise, the Regulators remained busy. They sent messengers to attempt to organize units in Bute, Edgecombe, and Northampton counties.

In Rowan, they denounced the Assembly for passing a 'riotous act', swore they would pay no fees, resolved that no judge or king's attorney should hold any court in Rowan, threatened death to all clerks and lawyers who came among them, and declared Edmund Fanning an outlaw whom they could kill on sight. -Conner, pp. 315-316. At the March 18 meeting with his council, Governor Tryon presented an intercepted letter from Rednap Howell to James Hunter. Howell fairly shouted the Regulator's defiant attitude:

I give out here that the Regulators are determined to whip every one who goes to Law or will not pay his just debts or will not agree to leve his cause to men where disputes; that they will choose Representatives but not send them to be put in jail; in short to stand in defiance and as to thieves to drive them out of the Country . . .

The council responded by giving Tryon permission to call out the militia. In point of fact, Tryon already had sent at least one call some two days before receiving this official permission, stating "it is the Intention of Government to raise a Body of Men to suppress the Insurrections in the Western Counties." Judges Martin Howard, Maurice Moore, and Richard Henderson wrote the governor, declaring that they felt it unwise to hold a planned session of court scheduled for March 22 in Hillsborough. Judge Henderson suggested that, instead, a special Court of Oyer and Terminer could be held in Granville County, and the measure was adopted. Preparations were now underway for a militia expedition into the backcountry. Tryon, as commander-in-chief, ordered General Hugh Waddell to march the Cape Fear militia to Salisbury. Wadell was to overcome the Rowan Regulators, raise the western militia, and march on Hillsborough from the west. Tryon, in command of the eastern militia, was to proceed directly to Hillsborough and link with Waddell. Both leaders experienced some difficulty in raising men. Tryon's army finally consisted of 1,068 men, of which 151 were commissioned officers; Waddell was able to raise only 248 men, of which 48 were officers.

By March 9, 1771, Tryon's army had reached Hillsborough, having met no opposition on his march. Waddell did not fare as well. First, a group of disguised Regulators attacked and destroyed a powder shipment being sent to the militia, ambushing the wagons on Rocky River near the present town of Concord. Second and more directly:

……on Thursday evening the 9th (of May), the Regulators to the number of 2,000 surrounded (Waddell's) camp, and in the most daring and insolent manner required the General to retreat with the Troops over the Yadkin River, of which he was then within two miles . . . The general finding his men not exceeding 300, and generally unwilling to engage . . . was reduced to comply.

Tryon and the Regulators received news of Waddell's rebuff on the same day-March 12. The Regulators issued a call for all men to assemble at James Hunter's plantation, to prevent Waddell and Tryon from linking forces. Tryon held a council of war, and it was decided that the army would march down the Salisbury-Hillsborough road to join Waddell as soon as possible. On Monday, May 13, the Loyalist forces made a strong camp on the west bank of Great Alamance Creek. Here, Tryon remained through Wednesday, May 15. About 6:00 p.m. that evening, he received a petition from the Regulators, some 2,000 of which were camped about 5 miles westward. The petition accused the governor of being prejudiced against their cause and determined to bloodshed. It asked that he halt his march and hear the Regulator grievances. Tryon's reaction was swift---"It was determined that the Army should march against the rebels early the next morning, and that the Governor should send them a letter offering terms, and in case of refusal attack them."

Soon after 7:00 a.m. on Thursday, May 16, 1771, the militia began a march westward from Great Alamance Camp. About two miles along the march, three small brass cannons were fired, signaling the men to form two battle lines---a test of their readiness in the event of an attack. Following the successful completion of this maneuver, the militia returned to column formation and continued their march. By 10:00 they were within one-half mile of the Regulator camp. Again they halted and formed battle lines. Governor Tryon dispatched his aide, Captain Malcom, and the Sheriff of Orange County to the Regulator lines. They carried with them the governor's answer to the previous day's petition. Admitted to the enemy camp, the sheriff and aide made their way around the loosely-assembled groups of men, pausing four times for the sheriff to read aloud the governor's answer:

In answer to your petition, I am to acquaint you that I have been attentive to the true Interest of this Country, and to that of every Individual residing within it. I lament the fatal Necessity to to which you have now reduced me, by withdrawing yourselves from the Mercy of the Crown, and the Laws of your Country, to require you who are Assembled as Regulators, to lay down your Arms, Surrender up the outlawed Ringleaders, and Submit yourselves to the Laws of your Country, and then on the lenity and Mercy of Government. By accepting these Terms in one Hour from the delivery of this Dispatch you will prevent an effusion of Blood, as you are at this time in a State of War and Rebellion against your King, your Country, and your Laws.

Each time the sheriff read this message, he was interrupted with hoots and catcalls. The Regulators would not heed Tryon's ultimatum. Meanwhile, the Loyalist army was slowly advancing on the Regulators, a vanguard of which were also moving forward. Soon the two groups were in sight of each other. The Regulators, in high spirits, waved and taunted the militiamen, then made their way back to the main body of their comrades. When the sheriff and aide returned to Tryon, they brought the news that "the Rebels ... (had) rejected the Terms offer'd with distain . . . (saying) they wanted no time to consider of them and with rebellious clammor called out for battle." It is somewhat doubtful that the Regulators believed a fight would ever take place. Tryon's officers now requested that there be an exchange of prisoners, two of their fellow-officers having been captured by the Regulators. It was agreed that Tryon would offer an exchange of seven Regulator prigoners for the two men. Messengers went between the two lines, but between eleven and eleventy-thirty in the morning, the governor began to suspect that the Regulators were merely stalling for time. He sent them a last message,"cautioning the Rebels to take care of themselves, as he should immediately give the signal for action." According to traditional accounts, the Regulators' reply was "Fire and be damned."

The governor ordered the cannoneers to give the attack signal; there was hesitation. Again, this time more forcefully, the governor gave his order, and five cannon broke the May stillness. Immediately, the militia's first line fired a volley, then kneeled to reload their weapons as the second line discharged their guns. The Regulators, without battle plan, officers, or discipline, scrambled for cover. Soon men were crouched behind rocks and trees, each man waging his own private war against the unified militia. The battle lasted two hours. Then the Regulators' fire slackened and the militia's cannon ceased. With its left wing in disarray, the militia began moving forward. Officers frantically shouted and signaled, until the entire army was cautiously advancing through the trees. The Regulators were fleeing. The militia captured some fifteen prisoners, and once inside the Regulators' former lines, found seventy saddle horses and quantities of supplies and ammunition. In spite of the apparent fury of the battle, only nine Regulators and nine militiamen had been killed. Sixty-one militiamen and an undetermined number of Regulators had been wounded.

By 2:30 p.m., the militia was alone on the field. Wounded of both the militia and Regulators were loaded into wagons, and the army and its prisoners marched back to the camp on Alamance Creek. In camp, wounded Regulators and militiamen alike, were treated by Tryon's own surgeon. Under terms of the Johnston Riot Act, the Regulators were outlaws who could be killed on sight. Now, shocked by the death of their comrades, the militiamen wanted this revenge. Thus, on the evening of Friday, May 17, after the dead Loyalists had been given military funerals, captured Regulator James Few was "hanged at the head of the Army." On this same day, Governor Tryon offered a proclamation of pardon to all Regulators who would swear a loyalty oath to the government. Only Herman Husband, Rednap Howell, James Hunter, and William Butler were exempt from this pardon, and they had all fled the country. During the next few days, militia units scoured the countryside. The main body of the army stayed at Alamance Camp. On Sunday morning before daybreak, Regulators raided a sentry post, shooting and wounding one sentry, and capturing another.

The days were marked by heavy spring rains. On Tuesday, May 21, the army marched to James Hunter's farm, burning his dwelling and outbuildings. In the evening of the same day they proceeded to Herman Husband's plantation and took possession of it, although they could find "no account of Husbands after the action." On Friday, May 31, General Waddell, having left his forces at the Yadkin, joined Tryon. Meanwhile, Colonel Edmund Fanning had captured Captain Benjamin Merrill, a Regulator. On Saturday, Waddell's forces arrived in camp, just in time to take part in one of the few humorous episodes of the whole campaign. The army had camped on Captain Merrill's plantation, and had pastured their horses nearby. These animals were allowed to wander free, but had been belled so they could be located. About midnight, a group of soldiers raided some bee-hives near the spot where the horses were pastured with near-disastrous results. An overturned hive of enraged bees attacked the horses, which bolted and ran. Smashing through a rail fence, they bore down on the sleeping camp, their bells clanging and the horses themselves screaming in fright and pain. Militiamen awoke with a start, grabbing muskets and preparing to defend themselves against the surprise Regulator attack. As Tryon's journal-writer put it, "this consternation . . . cast more horror on the waking imagination than anything else that happened during the whole service!"

TRYON'S AMNESTY PROCLAMATION 31 MAY 1771

North Carolina. By His Excellency William Tryon Esquire His Majesty's Captain General and Governor in chief in and over the said Province. A Proclamation. Whereas I am informed that many Persons who have been concerned in the late Rebellion are desirous of submitting themselves to Government, I do therefore give notice that every Person who will come in, either mine or General Waddells Camp, lay down the Arms, take the Oath of Allegiance, and promise to pay all Taxes that are now due or may hereafter become due by them respectively, and submit to the Laws of this Country, shall have His Majestys most gracious and free pardon for all Treasons Insurrections and Rebellions done or committed on or before the 16th Inst., provided they make their submission aforesaid on or before the 10th of June next. The following Persons are however excepted from the Benefit of this Proclamation, Viz. All the outlaws, the prisoners in Camp, and the undernamed persons, Samuel Jones, Joshua Teague, Samuel Waggoner, Simon Dunn, Jr., Abraham Creson, Benjamin Merrit [Merrill], James Wilkerson, Sr., Edward Smith, John Bumpass, Joseph Boring, William Rankin, William Robeson, John Winkler and John Wilcox. Given under my Hand and the Great Seal of the said Province at Hainay Camp this 31st May a Dom 1771. Wm. Tryon God save the King.

(The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Vol. 8, 1769-1771, By William L. Saunders, Secretary of State, Raleigh NC 1890).

During the first part of June, the joint forces of Tryon and Waddell marched to the Moravian settlement of "Bethlehem" (Salem?), where they celebrated the King's birthday and otherwise refreshed themselves. Afterwards, General Waddell marched 600 men to Rowan and Tryon counties to "bring the Inhabitants to a submission to Government." On Friday, June 14, the army was again in Hillsborough. The occasion was the first day of a special Court of Oyer and Terminer called by the governor under terms of the Johnston Riot Act. Chief Justice Martin Howard and Associate Justices Maurice Moore and Richard Henderson conducted the court, at which a jury tried fourteen captured Regulators on charges of high treason. For security, the fourteen prisoners had been marching with the army since the Battle of Alamance. Twelve Regulators were found guilty and were brought before the bench, where Judge Howard read the sentence for high treason against the crown. According to a contemporary newspaper account, Howard's chilling words were:

I must now close my afflicting Duty, by pronouncing upon you the awful Sentence of the Law; which is, that you... be carried to the place from whence you came, that you be drawn from thence to the Place of Execution, where you are to be hanged by the Neck; that you be cut down while yet alive, that your Bowels be taken out and burnt before your Face, that your Head be cut off, your Body divided into Four Quarters, and this to be at his Majesty's Disposal; and the Lord have Mercy on your Soul.

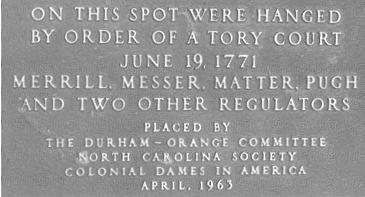

Of the twelve found guilty, six men were hanged---hanged only, since the gruesome details of the sentence had been omitted from actual execution practices for centuries. The names of only three of the condemned men have been ascertained:

Benjamin Merrill, Robert Matear (Matter), and James Pugh. Six of the men were pardoned at Tryon's behest: Forest Mercer, James Stewart, James Emerson, Hermon Cox, William Brown, and James Copeland.

Although the punishment for high treason also included confiscation of the guilty man's property, Tryon later appealed to the King on behalf of the condemned men's families, and their property rights were retained. The actual hangings took place just outside Hillsborough. A spot had been selected for erecting the gallows, and land around this spot was cleared for assembly of the army. The prisoners were escorted to the place of execution by the entire body of militiamen. After the "final words" of Merrill, who pled for his family's property and denounced his own "delusion," and Pugh, who remained defiant, the prisoners were hooded and the ropes placed around their necks. As the traps were sprung, the only other sound came from the militia colors flapping in the wind.

Two days later, Tryon bid farewell to his troops and hurried back to New Bern. Recently, he had been notified of his appointment as Governor of New York, and in less than a week he would leave the colony forever. Edmund Fanning would follow Tryon to New York, and would become the Governor's personal secretary. Both men would continue to rise in rank and honors. Within six weeks after the Battle of Alamance, over 6,000 former Regulators had taken the oath of allegiance and-received pardons. The movement had been crushed completely.

Two opposing myths have grown up around the Regulators and their movement. The first claims that Regulator principles were the same as those of the American Revolution and that, therefore, Alamance could be considered the first battle of that Revolution. There is much historical evidence to the contrary. Repeatedly, in petitions, "advertisements," and private letters, the Regulators swore allegiance to the British crown. Whereas the patriots of the American Revolution wanted a new government, the Regulators wished to reform the existing one. As historian R. D. W. Connor comments

A revolution involves a change of principles in government and is constitutional in its significance; an insurrection is an uprising of individuals to prevent the execution of laws and aims at a change of agents who administer, or the matter of administering affairs under forms or principles that remain intact.

The Regulator movement, then, must be regarded as an "insurrection."

The second myth, perhaps generated in reaction to the first, claims that most of the Regulators became Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. One reason for this belief seems to be based on the words of Tryon's successor, Governor Josiah Martin. During late 1775 and early 1776, Martin reported that the Highland Scots and the Regulators could be counted on to put down rebellion in the colony. After all, the governor had heard or seen countless oaths of loyalty from both the former Regulators and the Scotch survivors of "Butcher Cumberland" who emigrated to America---necessary prerequisites for their pardon. The Scots, moreover, seemed to have possessed a genuine loyalty to their conquerors. As for the Regulators they were in no hurry to align themselves with their former enemies---the men who had recently become such strong patriots were the very same who led the government and militia against the Regulators. Many Regulators did become Loyalists, but others were equally ardent as Whigs, and still others, smarting from the defeat at Alamance, managed to maintain a certain flexibility throughout the entire war. Former Regulators, therefore, could hardly be considered as a single class during the Revolution. As for Governor Martin, his brave pronouncements were halted by the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. A handful of former Regulators had joined a group of Highland Scots on a march to Wilmington, where a rendezvous with other Loyalist troops was planned. On the march, Whig forces surprised and defeated this group at Moores Creek Bridge, a battle sometimes called the "Lexington and Concord of the South."

Yet the Regulation did leave a positive mark on North Carolina and United States history. After the Battle of Alarnance and the Hillsborough trials, several letters and articles appeared in the Boston and Philadelphia newspapers---papers and cities strongly identified with the growing spirit of dissent. The letters and articles reported Regulator events in North Carolina, and were strongly biased against Tryon and his government. The bias was reinforced by Herman Husband's propaganda---"An Impartial Relation" (1770), and the series of articles collectively entitled "A Fan for Fanning and a Touchstone for Tryon" (1771).

In North Carolina the flurry of Regulator propaganda was publicly decried, even to the extent of burning copies of the Massachusetts SPY newspaper and hanging its editor and associates in effigy---an event which took place in New Bern. In several of the northern colonies, however, the publications caused public stir and sympathy for the Regulators at a time when opposition to British government was growing. One Boston man, for instance, was moved to name his pet spaniel "Tryon." The campaigns of the Regulation had served another purpose as well. Marching with Tryon on his Alamance expedition were men who would later become prominent leaders of the Revolutionary War effort. Among these were Alexander Lillington and James Moore---Whig heroes at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge; Richard Caswell, delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, one of the principal authors of the 1776 constitution of North Carolina, first governor of the newly-independent state; Francis Nash and Griffith Rutherford, American officers during the Revolutionary War. Until Alamance, many of these men had been only gentlemen soldiers who knew little of each other or of the realities of military life. It is ironic that in later years the enemies of the Regulators would become the champions of a reformed government.

The Regulator spirit had a direct effect on the formation of the State of North Carolina. Before the Battle of Alamance, the principles of the Regulators had spread over much of the colony, and these principles remained, to be incorporated into the state's first constitution:

…..We, the Representatives of the Freeman of North Carolina, chosen and assembled in Congress for the express Purpose of framing a Constitution under Authority of the People, most conductive to their Happiness and Prosperity, do declare that a Government for this State, shall be established in Manner and Form following, to wit, . . .

Section XIII. That the General Assembly shall by joint Ballot of both Houses, appoint Judges on the Supreme Courts of Law and Equity, Judges of Admirality, and an Attorney-General, who shall... hold their offices during good Behaviour.

Section XXV. That no Persons who heretofore have been, or hereafter may be, Receivers of Public Monies, shall have a Seat in either House of General Assembly, or be eligible to any office in this State, until such Persons shall have fully accounted for and paid into the Treasury, all Sums for which they may be accountable and liable.

Section XXVII. That no Member of the Council of State shall have a Seat either in the Senate or House of Commons.

Section XXX. That no Secretary of State, Attorney-General, or Clerk of any Court of Record, shall have a Seat in the Senate, House of Commons, or Council of State.

Section XXXV. That no Person in the State shall hold more than one lucrative Office at any one Time...

Section XXXIX. That the Person of a Debtor, where there is not a strong Presumption of Fraud, shall not be confined in Prison after delivering up, bona fide, all his Estate, real and personal, for the Use of his Creditors...

Section XLIX. That the Declaration of Rights is hereby declared to be Part of the Constitution...

Section XLV. That any Member of either House of the General Assembly shall have Liberty to dissent from, and protest against any Act or Resolve think (sic) injurious to the Public of any Individual, and have the Reasons for his Dissent entered on the Journals.

The Declaration of Rights attached to the Constitution listed one final precept:

. . . the Legislative, Executive and Supreme Judicial Powers of Government ought to be forever separate and distinct from each other.

Two hundred years have elapsed since the Battle of Alamance, a battle that still remains a tragedy. A government, supposedly dedicated to the good of the people, at first failed to listen to these people. Later, the people failed to allow this government time to act. There were many opportunities for both sides to work toward a solution of problems, but neither was willing to communicate when and where it mattered. Passions and prejudice, not reason and logic, began to rule in the colony---and the predictable end of this emotional response to practical problems was needless violence and death.

SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

© 1997-2003, Wallace L. McKeehan, All Rights Reserved