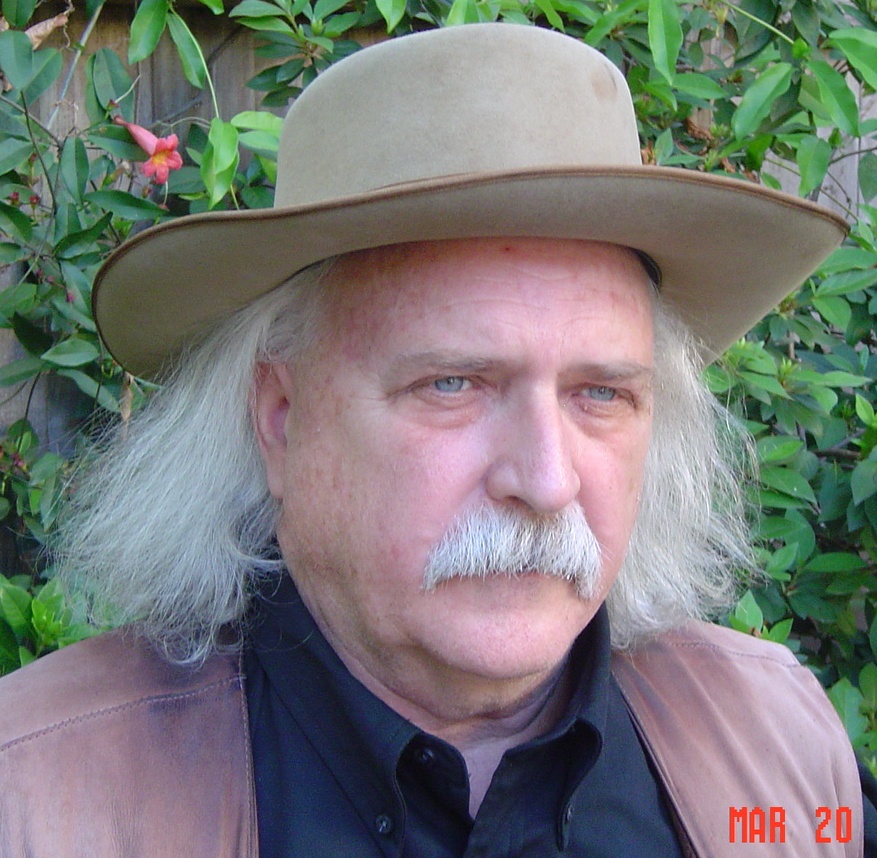

SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

Additional comments and opinions by Don Guillermo can be found at the DeWitt Colony Feedback, Forum, and The Texas Web Consortium Forum. Responses to these opinions are solicited and appreciated. "Had the Mexican presidial system succeeded, would there still have been a Texas Revolution?" The following is based on the assumption that the question refers to the Terán recommendations of 1827-1829 that precipitated President Bustamante's Decree of 1830 and Commanding General of the Eastern Interior Provinces Teran's attempt to implement the decree, which unfortunately, had gone beyond his recommendations by including principles most objectionable to Texians: Art. 3. ...central government commissioners shall supervise the

introduction of new colonists... Teran's strategy was to encircle the main settlements of Anglo colonization and control immigration and contraband trade. He stationed Col. José de las Piedras at Nacogdoches with 350 men, Col. John Davis Bradburn at Anahuac with 150 men, Col. Domingo de Ugartechea at Velasco where he built a fort, Lt. Col. Francisco Ruíz at Tenoxtitlán on the Brazos River (current Burleson County) who built and staffed a fort and Col. Peter Ellis Bean who occupied Ft. Terán on the Neches River. Terán was a sincere and well-meaning Mexican nationalist, his dream was that the series of military settlements and forts would serve as foci for subsidized native born Mexican and European immigrants, a system not unlike the earlier presidio-villa system in New Spain, but without the church's involvement. I believe that the agenda of Terán and his successor Tadeo de Ayala was to balance the Anglo population of Texas with native born immigrants and those from other countries unlike the dictatorial Mexican leaders who subverted the liberal Federalism of the Mexican Republic. Like their Spanish predecessors, the central government miserably failed to sincerely support both the military efforts for security and the attempts at colonization of Texas by native-born Mexicans and Europeans for a variety of complicated reasons. Even more importantly as realized by almost all true Republican Hispanic-born, native Tejano and Anglo-Mexican patriots of the period, military attempts to dictate and control Texas were futile in the long run. These liberal principles and the Mexican Republic's potential to benefit from them were betrayed by racist, self-serving and corrupt leaders, the prime example of which was Santa Anna. With the failure of the central government of Mexico to grant Texas independent statehood in the Republic and assimilate and learn the principles of self-determination and Republicanism from them, revolution became inevitable with subsequent events. The inevitability of revolution and impending loss of Texas to the Mexican Republic was no more dramatically realized than by Gen. Manuel Mier y Terán himself when on that fateful morning of 3 July 1832 he awoke early, dressed in his most immaculate uniform and plunged his battle sword through his own heart. The day before he had written his friend and associate, minister Lucas Alamán, predicting the loss of Texas. He expressed dismay and probably saw the future impending catastrophe and civil war coming as Santa Anna assumed leadership of the Mexican Republic under the guise of liberty and the Republican banner. He remarked "how could we expect to hold Texas when we do not even agree among ourselves?" 20 January 1998 Alamo de Parras War Room What was the Significance of the Battle of Bexar? Remember Bexar" should be an equally strong symbolic cry against corruption, greed, dictatorship and for self-determination as "Remember La Bahia", "Remember the Alamo." This writer agrees with Alwyn Barr in Texans in Revolt: The Battle for San Antonio 1835, who contends that the significance of the struggle for Bexar (Concepcion, Grass Fight and Siege and Battle of Bexar combined) is equal to or greater to that of the Alamo, Goliad and San Jacinto whose glamour and myths have shadowed it. The taking of Bexar shaped the future course of the Texas Revolution. The struggle for San Antonio: 1. demonstrated that Texian volunteers and minutemen could come together with elected leaders and battle plans in successful common cause against racist militaristic dictatorship, oppression and despotism. 2. showed that Texian patriots were not alone in their struggle and could rely on response and performance of volunteers from the United States. This, of course, contributed to Mexican government officials? paranoia that the Texas rebellion was due to outside influences, an ancient and current political ploy by despots to justify "deguello." 3. demonstrated unity between Hispanic Tejano patriots (distinguished them from Tories), Anglo-Mexican Texian colonists and U.S. volunteers (many who would become Texans forever) in concept and on the battlefield. Having held back from active participation in the Texas Consultations of 1832 and 1833 along with the majority of loyal Anglo-Mexican, DeWitt Colonists, Bexareños and Tejanos became active participants, e.g. the Capts. Juan Seguin and Placido Benevides and their men. Loyalty or neutrality based on birthright and race rather than principles was challenged more than ever before. Unnoticed by most historians is also the unity and contribution exhibited by black Texians Hendrick Arnold and Greenberry Logan and probably others unnamed, both free and bonded. 4. demonstrated the vulnerability of a well-trained professional and potentially honorable Mexican army when they are in support of despotic goals, do not have the support of the local population and are far from their supply sources. Mexican army desertions not to mention effect on morale of sympathizers to the Federalist cause played no small part. Jose Maria Gonzales appeal to Federalist sentiments among the Mexican troops is thought to have had impact. In specifics the struggle: 1. was a training exercise, test of motive and predictor of performance for militiamen and junior officers like Bowie, Travis and Fannin that became later commanders with varying degrees of success. Fannin and Travis were around, but did they really actively participate or have any impact? Fannin and Travis were not there with Old Ben Milam at the final assault. Barr argues that only Bowie showed leadership potential worthy of promotion at Bexar, e.g. organization of defense at Concepcion and cavalry action at the Grass Fight. Over 80 at Bexar died with the above three and all achieved heroic martyr status for the cause independent of the debatable strategic correctness of their commands. The action was also a training ground for future successful military and political leaders, always colorful and controversial, examples like Ed Burleson, William Cooke, Frank Johnson, Juan Seguin and Thomas Ward (lost a leg in the battle). 2. was an addition to the evidence that empresario Don Esteban (Stephen) Austin stands head and shoulders above any other individual in Texas history as truly the "father of Texas" who charted its citizens transition from colonial Mexican to independent Republicans, always with the welfare of Texans in mind. In six weeks, Austin put together a successful fighting force beginning in Gonzales despite his poor health after imprisonment in Mexico. Pressed harder and harder by hawk extremists Austin "had only limited military experience, like Abraham Lincoln a generation later the Texan leader quickly came to understand the need to defeat the opposing army" to save the Texas "union" (quotes from Barr). Austin realized the importance of removal of the enemies base from the historic capital of Texas. 3. showed the toll taken on local citizens (Bexarenos), both stress on loyalties and daily life, when their homes are the actual battleground. DeWitt Colony leaders were "happy," after confrontation over the cannon, to see the field move from Gonzales to Bexar (Gonzales was burned by Houston's army after the Alamo defeat). As pointed out by another contributor on this issue, there is evidence that the successes of Anahuac, Velasco, Nacogdoches, Gonzales and now Bexar caused an underestimation of the Mexican army and its resolve despite its misguided leadership. One of Fannin's men after capture at Goliad is quoted as admitting that his former experience in fighting Mexicans had led him to "contempt for them as soldiers, and led him to neglect to take precautionary measures as were requisite." Barr remarks "perhaps Fannin should have stayed through the attack on Bexar, he might have gained a more realistic assessment of his adversaries." He may have been riding on the coattails of Bowie in the action at Bexar. Barr points out that Cos conducted a careful defense of Bexar doing his best to conserve minimal supplies and support. Ugartechea and Navarro performed an unbelievable forced march to bring replacements with their untrained troops. Commander Nicolas Condelle of the Morelos Battalion led the most tenacious defense and argued against surrender to the last. An interesting question related to "How would you evaluate Sam Houston as a military commander?" is where was Sam Houston during the struggle for Bexar? He is known to have visited the volunteer army at Salado Creek in late October. Why did Houston overall have such an aversion to Bexar to the extent that he hardly ever appears there in his career from beginning to end? Theories are (a) that Houston sought command and political glory from the beginning and the Bexar troops did not turn to him for leadership. Early on he saw himself in competition with Austin for leadership and power and Austin clearly was the chosen leader of the struggle for Bexar; (b) he was doubtful of the value of the campaign as he was with defense of the Alamo. Houston cronies at Bexar appear to be those opposed to the battle plans of Austin and Burleson; or (c) at that time in 1835 Houston was simply not interested in the history or future of Texas relative to advancing his personal fortune in the Texas land of opportunity. According to Francis R. Lubbock in Six Decades in Texas the Battle of Bexar was "the most glorious feat of arms of the Texas Revolution." Richard Santos in Six Flags of Texas says "the departure of the forces under Cos was the turning point in the struggle for Texas independence. Hereafter, all Mexican troops in Texas would be invaders, not defenders, and Texas was destined to remain Texan evermore." Mexican officer Sanchez Navarro who later fought at the Alamo may have been referring to more than the immediate battle of Bexar when he commented "All has been lost save honor!" 25 January 1998 Alamo de Parras War Room William Barrett Travis' man-servant, Joe, asserted that Travis was killed in the heat of battle. Other sources have hinted he may have committed suicide. "How reliable was Joe's account concerning the death of William Barrett Travis?" Joe's description of Travis getting his head blown off in a bravado rush to the wall after getting off only one shot is "debatably" consistent with the man's immaturity, ignorance, poor judgement and erratic adventurism from the time he arrived in Texas: 1. Ignorance of law, particularly Mexican law, although he claimed to be a lawyer at Liberty and Perry's Point (Anahuac)

Mexican law regarding slavery (inland areas of the Austin and DeWitt Colonies were exempt, but not the 10 league coastal area) and the rule of law when he burst into Col. Juan Bradburn's compound as advocate for slave owners demanding release of the black men before Bradburn could determine what the current policy was on the issue. 2. Resort to treachery when his demands were not met, e.g. the hoax that an army was headed for Anahuac from the Sabine to take over the Anahuac garrison; and the seduction of Lt. Subaran and men of the garrison with aguadiente, if one is to believe the memorial of Col. Bradburn after his demise. 3. Failure to respond to duty as major of Regular Texian Artillery at the 3rd Consultation at San Felipe, Nov. 1835 4. Disappearance before the moment of decision at Bexar when Old Ben Milam made the decisive call to take the town. 5 .According to some, failing to wisely abandon the Alamo in the first place. At the end, certainly a disrespect for Centralista marksmanship? 03 February 1998 Alamo de Parras War Room In response to an article implying that the Troutman flag was the first flag of Texas Independence The Troutman Flag There are many theories and credits related to the origin of and the first Lone Star, symbol of the Republic and subsequent State of Texas. Equally numerous are references to inventors or the first to display the Lone Star, all patriotic gestures reflecting pride in the unequaled unfolding of the principles of freedom and self determination which the Lone Star of today represents. To refer to Johanna Troutman as the "Betsy Ross" of Texas is akin to crediting Mary Long with being the "Mother of Texas" because she gave birth to a child in 1819 under the flag of her husband's independence filibustering expedition often known as the "second Republic of Texas." From what I can determine, the first banner that flew the Lone Star was the red and white ensign of Col Dr. James Long in 1819 while Texas (actually the New Phillipines) was a part of New Spain, the Kingdom of Spain . In essence the evolution of the Lone Star banner was a story in itself exhibiting the evolution of the diverse contributions and patriotic feelings which came together to result in the combination of coalitions, racial, regional and cultural backgrounds, philosophies and feelings, all with common goal of freedom and self-determination, which represent what Texas is today. After Col. Dr. James Long's banner appeared the dual stars on the Mexican tri-color of the free state of Coahuila y Tejas under the liberal Federalist Constitution of 1824 guaranteeing states rights and regional self-determination. Although I cannot find recorded proof, this writer feels that the Lone Star may have been one of the single stars of the two, a symbol of the first goal of Texians under the Republic of Mexico which was independent statehood separate from Coahuila within the Mexican Republic. The Lone Star appeared on multiple local banners flown by individual units which formed to fight for independence of Texas in late 1835, all independent of and earlier or concurrent with the Troutman banner. As a biased Son of DeWitt Colony, the words of our own Creed Taylor in his memoirs raises strains of regional pride and claim to the first most meaningful Lone Star that led to the series of resistance to dictatorship and despotism resulting in the independence of Texas....bear witness to the fact that the 'cannon flag' designed and hoisted [by the first Texian army] at Gonzales on October 10, 1835, was the first Lone Star that was ever caressed by a Texas breeze unless the honor should be given to the Dawson [Dodson] Company standard..." For more information of the evolution of Texas flags in general and the Lone Star in particular, See: DeWitt Colony Flags and Flags of Texas Independence. 28 February 1998 Alamo de Parras Forum Response to comment regarding a Dallas paper’s suggestion that Texas History is irrelevant to today’s mixed racial groups and perhaps should be discontinued as a course in Texas schools. If Texas History is simply the study of ancestry of Texas residents, "ancestors… on the wrong side or enslaved in 1836" and "Davy Crockett… and western movies about Texas" and such trivia then it should be definitely abandoned. It is more critical today to teach Texas heritage and history to middle school students than ever before and the problem is content---what is taught! If one does not understand Texas history than one will never understand Texas today and one’s role in its successes, failures and problems. If taught properly no history of any state in the USA or the world can reveal the lessons in microcosm and prototype found in Texas history as it evolved from an aboriginal wilderness to a state of the USA. From Texas history one will understand land and property rights, immigration and colonialism, regional independence movements, militarism, dictatorship, racism, slavery and economic class struggle, religion’s role in society, resolution of conflict between birth, family and principle, role of the individual versus the group, and impact of both the flawed and heroic traits of character on society. The Texas of today, its three primary racial and cultural groups and its key border state position did not suddenly appear yesterday, it is the product of nearly 300 years of slow and torturous evolution and struggle to build a free and prosperous regional society by essentially the same forces and major racial and cultural groups plus many smaller ones which compose the state today. If studied in depth, Texas history is European, Spanish, Mexican, Black and US history. It is time, not to discuss ablating mandatory Texas history, but to increase the relevance of the content and train a new generation of teachers who can creatively present it. 27 March 1998 Alamo de Parras Forum "Among Mexico's requirements for colonization was that each new colonist become Roman Catholic. What role did religion play in the Texas Revolution?" Despite the emotion generated by the principle and the popularity of the topic with those searching for hypocrisy and evil motive of Anglo-Mexican immigrants, the fact that the Roman Apostolic Catholic Church was the official religion of Mexico on paper had very little real impact on the settlement and eventual separation of Texas from the Federation of Mexican States at the local level. The subject often appeared in inquiries by potential immigrants to empresario Austin and other officials, but on average was much less of concern than economic issues. In reality, many were much more concerned with the lack of churches and schools at all on the frontier and would have preferred state-sponsored catholic to none at all. A great majority of Anglo-Mexican colonists were independent-minded frontiers people, Christian in concept, but ecumenical in practice, therefore, they were easily reconciled to becoming Catholic as long as the ritual were not enforced to the extent it would interfere with carving a society out of the wilderness. Ironically, the principle associated with having to become Catholic delayed the immigration of fanatic Protestants, themselves a threat to colonization goals and the eventual establishment of religious tolerance in Texas, and with Texas as an example, throughout a truly republican Mexico. This is not to say that evangelistic activity did not take place in the colonies, but most ministered quietly with respect for the official Catholic religion and often as not were individualists as to specific ritual and doctrine, teachers and often patriotic citizen soldiers. Among both Anglo- and Hispanic-Tejanos in Texas, there was hope for evolution of religious tolerance in a republican Mexico. Many native Tejanos raised for generations in the Catholic faith under Spain and Mexico were advocates of religious tolerance. Erasmo Seguin expressed the opinion that in fact Texas experienced religious tolerance under Spain, private worship would not be disturbed by Mexican authorities and immigration would not be limited to pre-existent Catholics as long as they were Christian. His opinion was confirmed by failure of a legislative proposal to restrict immigration to Catholics in 1824, which failed with only one vote for. Hope was high with the installment of President Guerrero in 1829 over unanimous opposition of the Roman Catholic ecclesiastics for modification of the Constitution of 1824 to include religious tolerance. The liberal and intellectual friend of Texas and empresario Austin, Gen. Manuel de Mier y Terán, supported freedom of religion in Texas and probably all of Mexico. The legislature at Montclova passed in 1834 "No person shall be molested for political and religious opinions, provided he shall not disturb the public order," although the act probably exceeded constitutional authority and may have been motivated by either land sale policy or against centralista rule. In sum prior to abrogation of the Constitution of 1824 and republican principles by the centralista dictatorship, government policy regarding the provision of the constitution specifying the official state religion was, in practice, tolerance. In Nacogdoches in 1832, a revival meeting by Rev. Alford and Bacon was opposed in concept by alcalde James Gaines and someone reported the meeting to Commandante Piedras. Piedras replied "Are they stealing horses?" The answer was "No." "Are they killing anybody?" "No." "Are they doing anything bad?" "No." "THEN LET THEM ALONE!" ordered the Commandante (From Thrall’s History of Methodism in Texas). In some cases, enforcement actually came from colonists who resented being proselytized to about a particular sect’s theoretical principles relative to the realities of the frontier. Article 5, section 1 of the Texian Constitution of 1836 hardly referred only to clergy of the Roman Catholic church:

In essence, the de facto religious tolerance in Texas in the 1830’s was the situation in many states that retained an official state religion at some stage on paper. Most took well into the 20th century to achieve religious tolerance or are still trying to achieve it today. This includes current European countries as England, Sweden, Holland and others, Mexico and American countries to the south who still retain an official state religion on paper. Finally, it is noteworthy that in none of the many memorials, declarations and documents based on consensus prior to the full Declaration of Independence in 1836 was the principle of religious freedom or anti-catholicism expressed specifically. On the contrary, until Texians were betrayed by the racist, self-serving and anti-religious dictatorship that took control of their government and threatened their lives, property and self-determination, their official documents supported the Constitution of 1824 with its dictate of a state religion with only the hope that it would be changed with time. All said about the local level in Texas, no doubt the re-union of church and state with power hungry ecclesiastics rushing to prostitute for Santa Anna, who welcomed them warmly, played a great role in the final separation and resistance as the threat of enforcement of religious and political belief threatened the de facto tolerance. May 1998 War Room Alamo de Parras Response to: A recent Houston Chronicle guest editorial contended that the "Alamo is a lie," the Texas War of Independence was for the retention of slavery and that Mexico under Santa Anna lost Texas because he took the "high road" on the slavery issue. Was Santa Anna the Abe Lincoln of Texas? Were the Alamo Defenders defending slavery? Was slavery an

issue in the Texas rebellion? Von Holst in Constitutional History of the United States 11, 553: "Settlers came with their slaves from the slave States [to Texas]. In this the heads of individual persons may have been haunted by far-reaching projects; but I can find no support for the assertion that back of it there was a definite plan of the South." Unlike the clash between North and South in the United States, slavery was a non-issue in the clash between Texians (and all Mexican Federalist and Constitutionalists) and the centralist Mexican dictatorship. However, the archives are replete with the agony and the struggle of Anglo and Hispanic Mexican Texians with the short and long term moral, economic, political and legal consequences of slavery (See Correspondence Concerning Slavery in Texas and Slavery in Early Texas by Lester Bugbee, 1898). In this respect, a full study and understanding of the struggle and unfolding of the institution of slavery within Texas in 1820-1836 is as far as one need look to see the complicated interplay of region, climate, economics, principle, law and race to understand the institution as it unfolded in the United States. Was Santa Anna the Abe Lincoln of Texas? Were the Alamo Defenders defending slavery? I am unaware of a complete personal history study on all Alamo Defenders which I hope will emerge sooner or later and for that matter all those in the service of Texian independence. However, there is no evidence that slavery even as a remote property issue would have been a motivational factor for the unique subset of defenders, the Gonzales Ranger Alamo Relief Force , who most clearly, aggressively and uniquely among Texians outside the garrison, demonstrated their willingness to defend the Alamo. This was after all "Houstonian" questions of doubt of centralist motives and resolve were disproved by the surrounding of the garrison and announcement of "deguello," no quarter by Santa Anna. Of those from the DeWitt Colony capital Gonzales who successfully penetrated surrounding centralist lines, at least 22 were homestead and property owners (or members of families who were) of record in the colony, legal and loyal citizens of the Republic of Mexico. Not one was clearly a soldier of fortune, filibuster or adventurer. Three were civil servants of record, most were farmers and ranchers, two were merchants and two were skilled blacksmiths with shops in Gonzales, the best of developing regional Texian society. Not one (or their family) of record brought slaves into Texas or held a slave at the time. Although not for certain because of lack of records, this conclusion may extend to all Alamo Defenders from the DeWitt Colony whose contribution per resident was larger than any other single municipality or district of Texas. Members of families of the Municipality of Gonzales, who comprised only about 4% of the total population of Texas, accounted for 20% of the casualties at the Alamo. Put another way, over 4% of the total population of the DeWitt Colony, among them their most productive landholders, ranchers and farmers as well as merchants and civic leaders, died in the Alamo while total Alamo casualties represented less than 0.5% of the total population of Texas. The personal histories, despite large gaps, of these Mexican citizens show clearly that they were motivated by immediate defense of family and their investment in the opportunity and promises given them by the libertarian principles of the Federal Republic of Mexico (see Andrew Kent story and William King family story). Personal loyalties to defenders in the garrison who were members of the community may have played a part. Secondary motivation was principle that they were defending personal and regional freedom to pursue a better life with minimal government interference, which most Anglo-Mexican immigrants had already gotten enough of in the land of their birth. This general conclusion may apply to the majority of Alamo Defenders and for that matter those who participated on the side of Texas and the Mexican Federalists, a surprising minority of Texas residents by the way, until the Mexican War of 1847. The continuous struggle of self-righteous academics and other apologists as Señor Olvera ("The Alamo is a Lie" article) for self-serving centralists, who view the world through "race war" glasses, to put the image of loss of and fear of liberation of bonded blacks in the minds of these patriots as they rode to Bexar and penetrated centralist lines as well as their co-defenders in the garrison is an interesting exercise in sociology (socio-pathology?) rather than historical perspective. 08/09/98 War Room Alamo de Parras Other than familial ties to Bejar, what were some of the reasons Mexican soldiers of the Alamo Company deserted to join the Texian Army? At somewhat of a loss to go at this issue directly in depth because of lack of familiarity with individual cases, my gut reaction is to answer simply that general loyalty to race and military duty was overridden by love of their Texas regional homeland, sympathy for libertarian federalist principles of regional self-determination, distaste for dictatorship and corruption and a belief that the Texian cause would win. I do find distasteful the modern authors, desperate for readers, who try to capitalize on racial differences and try every futile avenue possible to apologize and rationalize for this patriotic element’s position by implying that they were somehow coerced into their actions. The worst example is the continuing struggle to argue that the most unwavering Hispanic Texian patriot of them all, José Antonio Navarro, was somehow coerced into the Santa Fe Expedition and his unrelenting stay in Mexican prisons, punished and at risk of execution because he would recant not one inch in his position despite appeals of family and friends (compare this stance to Seguin and Flores).

In diversion of the question to a case history in which I am knowledgeable, I have been equally interested in analysis of the motives of individuals of typical Southern Anglo background who loyally served the Republic of Mexico in Texas, foremost examples John (Juan) Davis Bradburn and Peter Ellis (Pedro Elías) Bean. A distant cousin, Bean is the most intriguing. The counterpart of Hispanic Tejano descendants of Canary Islanders of 1836, Bean was the descendant of multiple generations of American Creoles derived from Northwest European immigrants to the American continent. Leading a career stranger than fiction while plotting his way from adventurer/filibuster, 10 years in Spanish prisons (vacillating between minimum and maximum security after escape attempts), revolutionary captain and trusted emissary of José Morelos, acquaintance of Jean LaFitte and participant under Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans, Mexican Colonel and Commander of Ft. Terán in implementation of the Bustamante Plan under Gen. Manuel Mier y Terán in Texas, trusted Indian agent during the Fredonian Rebellion and the Texas Revolution, self-imposed prisoner and subsequent parolee of Texian forces, and successful Texian businessman and extensive landholder in the Republic of Texas. While in Spanish prisons during periods of minimum security, he was a shoemaker, hatter, gunpowder chemist and explosives expert, while a Mexican Revolutionary a successful commander and munitions expert, while a Texian (both pre- and post-revolution) a lumber mill owner, building supply dealer, retail merchant, landlord, farmer, rancher and salt distributor. Although raising a Texian family of pure Tennessee stock with a Tennessee wife, he returned to a last few years of continued happiness with his waiting wife from days of the Mexican Revolution, the Doña Magdalena Falfan de los Godos at La Banderilla in Jalapa, dying just short of seeing Texas become a part of the United States of America. To this day, scholars cannot clearly peg him as Tennessee semi-literate hillbilly, nation-less soldier of fortune, Spanish army turncoat (he entered service of royal Spain and surrendered and joined insurgents under Morelos), Mexican revolutionary chieftain, Mexican Federalist, Mexican Tory during the Texas Rebellion, or discreet Mexican sympathizer with the anti-centralist Texian forces. I believe one thing he was clearly not, in contrast to Bradburn, was a Mexican Centralista. He was clearly a steady, productive and active Mexican-Texian, and as can be gleaned from the records, an optimistic, ingenious and resourceful one within the moment to moment maze of conflicting races, cultures, philosophies and individuals through which he plotted. Understanding his motives and how he pulled all this off without a rupture in security of his person, reputation and legal status without disgrace to his race, culture, country (whatever it was), colleagues and general environment may give insight into context-dependent decisions of loyalty and action including the motives of Hispanic Tejanos who joined the predominantly Anglo-Texian cause. Maybe it was maintenance of focus by appreciation for the little things at hand amid the larger titanic forces swirling around him, e.g. his good and only friend the quija while in Acapulco Solitary, the "shine" smuggled through the peephole of his cell by his lady friend (see Memoirs), and his appreciation of fine Tennessee whiskey and Virginia tobacco that was apparent from his receipts in the Nacogdoches Archives. 10/09/98 War Room Alamo de Parras Traitorous Conduct of Sam Houston Although at first cautious in regard to harsh critics of Houston (The San Jacinto Campaign: Generalship of Sam Houston and succeeding Alamo Forum), a study of events leading up to The Siege and Battle of Bexar convinced me to agree, not with Houston's vicious political enemies who wrote from their desks with "20-20 hindsight," but with contemporary, transient Gonzales residents George Huff and Spencer Jack who wrote over the heat and sweat of their lead molds and shop furnaces:

Written 28 Oct 1835, just after the victory at Concepcion and when morale was high to reduce and take Bexar after a month of siege. It appears that a price should have been put on Houston's head with similar justification put on that of John Williams at the first of the month:

11/23/1998 Alamo Forum Alamo de Parras In response to the question "Did Sam Houston as President, Governor or Senator visit the Alamo after Texas Independence?" Sam Houston clearly suffered from Alamo-, San Antonio de Bexar-, "West of the Guadalupe River"- and "South of the La Bahia Road"-phobia his entire political career and life. His interests, security and political ambitions lay in the east and the other regions were only trouble--independent pioneers interested in personal and regional autonomy, racially-different Hispanic Texians, wild plains Indians (different from his eastern chronies), and Anglo- and Hispanic-Mexican Federalists. The Alamo was particularly a monkey on his back keeping him in between a rock and a hardplace politically from start to finish. Reasons for his conduct prior to the Battle and Siege of Bexar have been discussed above. As the Alamo became both a tragedy and a symbolic rallying cry and shrine of sacrifice and libertarian visions, he was a loser politically, morally, etc, whatever the answer to either question---why did he order the future shrine destroyed and abandoned, or why did he fail to go to its rescue. Honoring the Alamo and associating with its mystique, as well as prior developments in Texas independence west and south of the Guadalupe/Gonzales had no clear political mileage for the narcissistic side of Houston, only potential liability, and detracted from the single stroke of luck that made him at San Jacinto. 08/07/99 Alamo de Parras Forum "Numerous Anglo-Texians married women of Hispanic ancestry (Tejanas) including notables as Colonel Peter Ellis Bean, James Bowie, Erastus Deaf Smith and John W. Smith, while there are fewer instances on record of men of Hispanic ancestry, either Tejano or Mexican, who married Anglo-women. Most Texian accounts, particularly when under fire or imprisoned, speak admiringly without sexist tone of native Hispanic women they encountered. Why the difference? The difference lies in the gap between the Mediterranean and Hispanic cult of machismo (macho) versus Anglo/Nordic male chauvinism. The difference is one which still exists today between males of the two societies and sub-cultures within cosmopolitan societies as the USA. Anglo-Texian women on the frontier were granted or one might say given the opportunity to earn equality by Anglo-Texian men largely out of necessity in carving a society out of the frontier wilderness with all its dangers from both depredating aboriginal vandals as well as threats to their reason for being from the hostile Centralista faction who gained control of the government of their adopted land. This equality was impossible to exercise by either an Anglo or Hispanic wife in a familial relationship with a male spouse dominated culturally by the cult of machismo. On average, it would be unthinkable for a macho male's spouse to mold bullets, load and fire rifles, kill and butcher animals, handle mule and oxen wagon teams and ride straddling horses like a male. Although there were many other cultural barriers, on average Anglo-Texian women were unwilling to forego their relative equality in a relationship dominated by machisimo, and the machisimo male was reluctant to accept those "unfeminine" qualities. In contrast, Tejanas and Mexicanas with equally strong potential for equality and rugged individualism to any Anglo-Texian more often accepted the rare opportunity (rare because of other cultural barriers) for relative equality and respect enjoyed when married to an Anglo-Texian husband. In response to a correspondent that suggested that the difference was because of prejudice, sex or profit. The profit motive may be on target at least in the case of the Bowie example, not for Bowie, but for his father-in-law, Don Juan Veramendi. Jim Bowie courted (always under the parents eyes of Don Juan and Josepha Navarro Veramendi) the beautiful 18 year old Ursala Veramendi for two years before Don Juan Veramendi would give her hand in marriage. On 22 Apr 1831, Bowie signed his marriage dowry contract before Bexar alcalde Jose Maria Salinas which included:

The partnership of Don Juan Veramendi and Bowie, with mostly Bowie's financial support and Veramendi's oversight, resulted in a modern cotton mill in Saltillo and other ventures beneficial to the economic development of Coahuila y Tejas. Bowie was never seriously involved in the operation, but much more interested in the excitement of searching for San Saba silver and relatively legitimate land deals, not Mexican land grants. The Bowie-Veramendi marriage and business contracts were tragically ended by the pale horseman carrying Asiatic cholera of 1833 (taking Bowie's wife, father-in-law, and other Veramendis) which devastated Mexicans including Mexican-Texians (notables as empresario Don Martin de Leon, alcalde of San Felipe John Austin, and to this writer his 5th greatgrandparents and DeWitt Colonists), a loss from which the teflon-coated swash-buckling land speculator, slave trader and "bravo" Bowie is believed to have never totally recovered personally (within days Navarro kin scarcely could recognize the previously care-free, now grieving, caballero). Hardly a relationship forged by prejudice and sex. After 15 years in and out of Spanish prisons and contributing to the Mexican independence movement under José Morelos, Texian Mexican Colonel Peter Ellis Bean earned the hand of Doña Magdalena Falfan de los Godos of Hacienda La Banderilla in Jalapa. Was sex and prejudice a factor that motivated the 50 year old arthritic chieftain to return to the Jalapan Doña who was waiting with open arms after his absence of over 20 years? Hardly! Well, maybe sex indirectly, the old chieftain had been earlier cuckolded by his Anglo wife Candace by co-habitation with who else, but Fredonian Rebellion leader and later Signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, Martin Parmer. I have not yet found details of the "love" stories that paired John Smith and Maria de Jesus Curbelo and "the eyes and ears of the Texian Army" Erastus Deaf Smith and Guadalupe Ruiz Duran, but I predict we will see the same general reasons as Bowie and Bean as well as most of the Anglo male-Mexicana female unions of consequence. Rejecting prejudice and sex, one might as well propose that John Smith's interracial marriage may have been motivated by political ambition. Smith was the first mayor of San Antonio de Bexar under the Republic of Texas, re-elected twice, through Mar 1838 with a council of all Hispanic Tejano aldermen, Manuel Martinez, Francisco Bustillo, Ramon Trevino, Pedro Flores Moreles, Gabriel Arriola, Rafael Herrera, Francisco Granado and Francisco A. Ruiz. He was succeeded in the office by Anglo William H. Dangerfield and then Hispanic Texian Antonio Manchaca in whose terms there was only one Anglo alderman. One interesting variant to the above sagas is the story of Anglo DeWitt Colonist Montraville Woods who was so lovestruck he got in a hurry to pair up with the lovely 14 year old Isabella, daughter of Francisco Hidalgo Gonzales and his wife, Procopia Hidalgo Valdes (Hidalgo being a title of noble ancestry). The couple's elopement caused a fairly heated protest by father Francisco to alcalde Cummins of San Felipe, 1826, calling for punishment of Woods (son of Zadock Woods and brother of Gonsalvo Woods of The Dawson Massacre fame) and return of his daughter. Proper Catholic marriage and dowry solved the problem and Montraville became his father-in-law's respected lifetime business partner and agent. Was this lifelong love affair driven by prejudice and sex? Hardly! Isabella bore 11 daughters and one son fathered by Montraville and outlived him by 49 years, never remarrying, but remaining an active member of the extended Woods family. As a widow, Isabella continued to manage the family lands and businesses aided by the children until her death at age 93 and registered her own brand in DeWittCo. She was buried beside her beloved Montraville among other Woods family members in 1906. Very doubtful whether motives other than love and loyalty were ever at play in this interracial affair. More interesting diarist descriptions of encounters with Hispanic women can be found in the Memoirs of Peter Ellis Bean and George Kendall, The Santa Fé Expedition, both while prisoners of Spain and Mexico, respectively. 11/24/98 Alamo de Parras War Room SONS OF DEWITT

COLONY TEXAS |